Chemotherapy is fundamental in the treatment of many types of cancer in dogs. The goal of chemotherapy is a little different in dogs than in people. Oncologists aim for a gain in life expectancy over what would happen without it, and to improve the quality of life for the dog being treated. The most important goal is to protect the bond between the owner and their dog.

Key Takeaways

- It is worth giving a dog chemo if the treatment has been proven to be effective for your dog’s cancer type. Talk to your veterinary team about the specifics of your dog’s case to determine if chemo is right for your dog.

- The average cost of chemotherapy for a dog is $150-600 per dose. Oral tablets tend to be less expensive, but depending on the drug it could be $200 or more a month.

- How long a dog stays on chemo depends on the cancer type and the chemotherapy used. The CHOP protocol for lymphoma is typically 19-25 weeks, while other protocols are significantly shorter.

- Chemotherapy is not usually as tough on dogs as it is on people. Veterinarians work hard to find dosages that are tolerated well by the dogs but still help to combat cancer and improve quality of life.

Chemo for Dogs is Worth Considering

You may have previous experiences with chemotherapy administered to humans with cancer and may be hesitant to make this choice for your dog. A common concern for dog lovers is whether or not chemotherapy will make their dog feel sick.

Dog Chemotherapy Is Lower in Dose

The truth is, less aggressive doses of chemotherapy are used in animals than in people. This minimizes adverse side effects.

Although chemotherapy in animals is typically not curative, when used appropriately, it can improve the quality and quantity of life for the dog being treated.

Some Dog Cancers Respond Well to Chemo

Lymphoma, a very common cancer in dogs, is particularly susceptible to chemotherapy.

The mean survival time of a dog with lymphoma who doesn’t get chemotherapy can range from a few weeks to a couple of months.

Some dog cancers, like lymphoma, respond quickly to chemotherapy, with both life quality and longevity extended.

However, dogs that undergo chemotherapy to treat lymphoma can often achieve a mean survival time of over a year. And they usually start feeling better after the very first chemotherapy session.

That’s a lot of time gained from chemotherapy. The survival time is extended, and dogs feel better when their cancer burden is lessened. This extra quality and quantity of life can be precious to dog owners and can improve the human-animal bond.

When is Dog Chemotherapy Recommended?

Chemotherapy drugs circulate throughout your dog’s body and can target cancer cells anywhere, so they are most useful for systemic treatment. Surgery and radiation, on the other hand, typically target discrete tumors.

In most cases, chemotherapy is used to treat patients with widespread disease, for tumors sensitive to drug therapy, or for potential metastatic disease that won’t be helped by local therapy such as surgery or radiation therapy.

The goal is to prolong survival while maintaining patients’ excellent quality of life during and after treatment.6

The goal in veterinary medicine isn’t to cure cancer with chemotherapy. The side effects would be too severe. Instead, chemo is recommended when it will significantly extend life and give good life quality compared to what would happen without chemotherapy.

Common Examples of Dog Chemotherapy

There are three primary types of chemotherapy used in dogs: conventional injectable, metronomic, and targeted chemotherapy.3

Each type of chemotherapy has different pros and cons.

Conventional Injectable Chemotherapy

The goal of conventional chemotherapy is to use the maximum tolerated dose of a chemotherapeutic agent over a predetermined period of time.

We should note that the the maximum tolerated dose in humans differs from that in dogs. Oncologists can ask humans to tolerate severe side effects. Veterinary oncologists cannot get consent from dogs for those severe side effects.

No one wants to see dogs suffer, so the maximum tolerated doses for dogs are much lower than for humans.

The maximum tolerated dose for dogs helps treat cancer without making the dog sick, or at least not too sick. Doses are adjusted from appointment to appointment based on how well the dog is doing.

A common example of conventional chemotherapy is the CHOP protocol for treating lymphoma. This multi-agent protocol utilizes a prescribed dose of chemotherapy for a predetermined period of 15 or 19 weeks.

Metronomic Chemotherapy

Metronomic chemotherapy is the uninterrupted administration of low doses of cytotoxic (cell-killing) drugs at regular and frequent intervals. Instead of one big dose of chemotherapy at a weekly appointment, the doses are smaller and more often.

Metronomic chemotherapy is given at home, not at the hospital.

The potential benefits of metronomic chemotherapy include less expense, less toxicity, and fewer trips to the veterinary hospital.

Lab work should be monitored every 3-6 weeks while on metronomic chemotherapy.

Cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, and lomustine (CCNU) are three examples of drugs used in metronomic chemotherapy protocols.

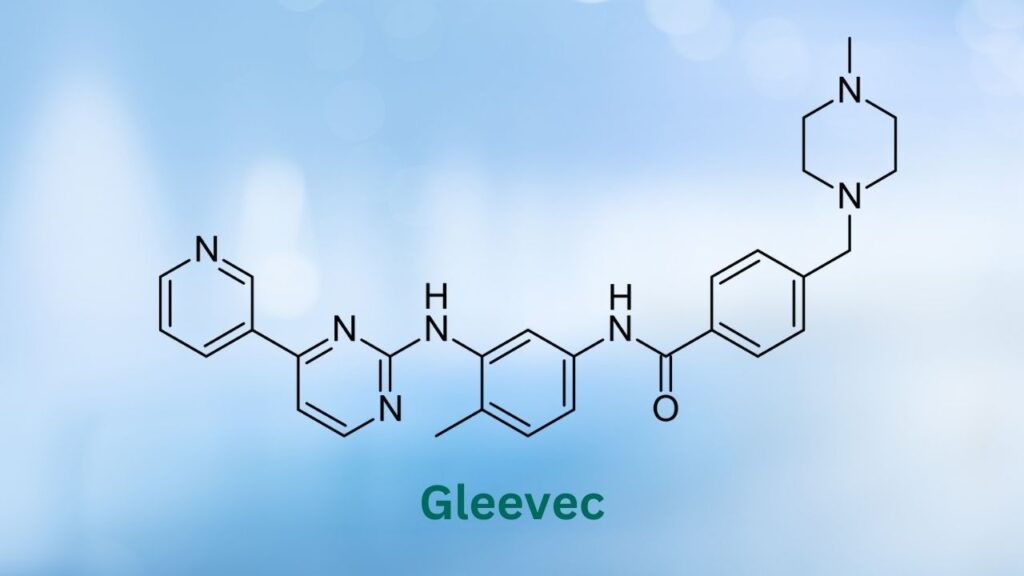

Targeted Chemotherapy

Recently, targeted chemotherapeutics have been incorporated into certain cancer treatment plans. Targeted chemotherapeutics attack a “target” on a cancer cell while doing less damage to healthy cells.

These chemotherapeutics can be prescribed as a sole agent, but are generally used in conjunction with surgery, conventional chemotherapy, or radiation therapy.

An example of a targeted chemotherapeutic used in veterinary medicine is the drug Palladia. Palladia targets and inhibits the tyrosine kinase receptor on overactive cancer cells. Blocking or inhibiting these receptors can slow down cancer growth.

Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Protocols

Another way to classify a chemotherapeutic protocol is to define it as single-agent or multi-agent.

A single-agent protocol is one in which a single chemotherapeutic drug is given alone. A few examples of chemotherapeutic agents that can be used as a single agent include:

- Alkylating agents: cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, lomustine

- Anti-metabolites: methotrexate, cytosine arabinoside

- Antitumor antibiotics: doxorubicin, mitoxantrone

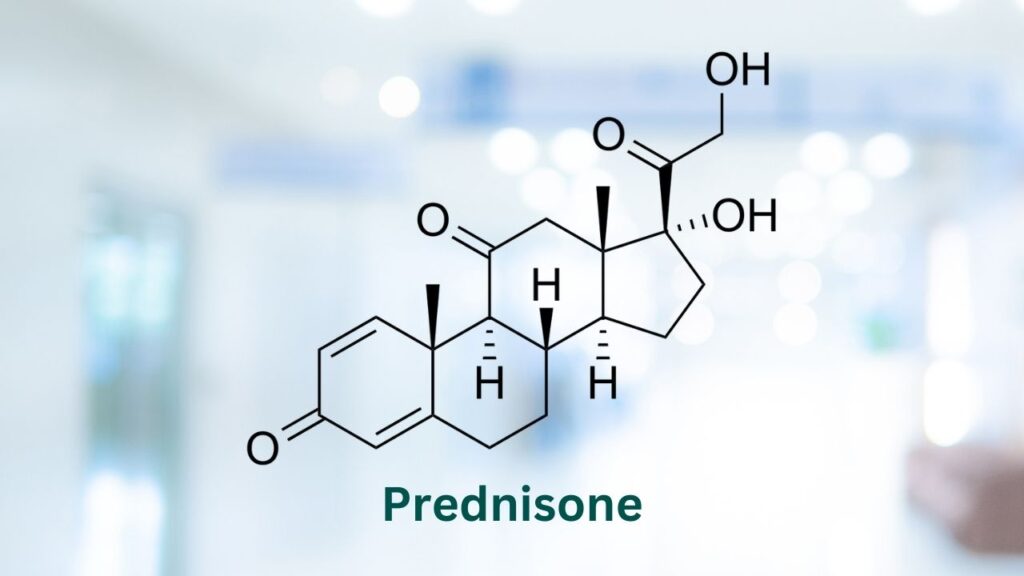

- Corticosteroids: prednisone, prednisolone

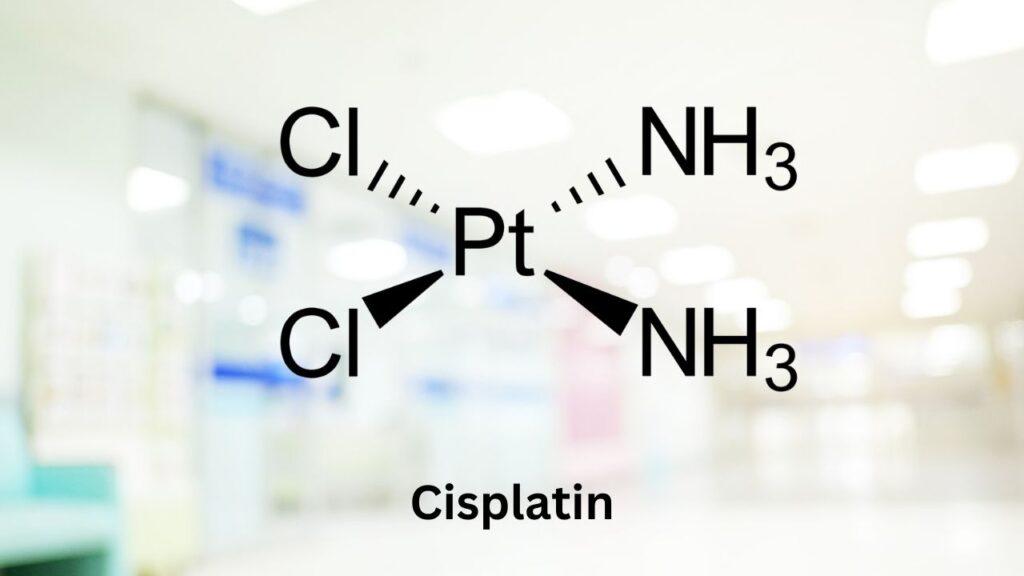

- Platinum compounds: cisplatin, carboplatin

- Plant alkaloids: vincristine, vinblastine

- Other miscellaneous agents: Tanovea, L-asparaginase

A multi-agent protocol is one in which multiple drugs are used in combination to have the best defense against abnormal cancer cells.

Chemo agents are like weapons used for battle. When more weapons are used to attack abnormal cancer cells, cancer has a harder time fighting back, and multidrug resistance is delayed.

Chemotherapy drugs are like battle weapons. Used together, cancer has a harder time fighting back.

Utilizing drugs with different mechanisms of action in conjunction has a better chance of achieving and maintaining remission.

Listed below are a few examples of multi-agent protocols used for the treatment of lymphoma:

- CHOP: cyclophosphamide (C), doxorubicin (H), vincristine (O), and prednisone (P)

- L-CHOP: L-asparaginase with the agents used in CHOP

- MOPP: mechlorethamine (M), vincristine (O), procarbazine (P), and prednisone (P)

- LOPP: lomustine (L), vincristine (O), procarbazine (P), and prednisone (P)

- COP: cyclophosphamide (C), vincristine (O), and prednisone (P)

How Chemotherapy Works

Chemotherapeutic agents can be used to increase both the length and the quality of life for patients with a wide variety of cancers.6

Chemotherapy aims to stop cancer cells that are continuing to divide uncontrollably, and it aims to kill rapidly dividing cells.2,14

Chemotherapy can have different goals:14

- Curative chemotherapy aims to eliminate all cancer cells from the body and make cancer go away completely. Curative chemotherapy is utilized more often in human oncology. Higher doses are given with the goal of “cure cancer.” These higher doses often yield greater side effects than would be considered unacceptable for most dog lovers.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy mainly aims to fight the cancer cells that could be left in the body after surgery but can not be detected (microscopic disease). The goal of this type of chemotherapy is to prevent recurrences.

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can often shrink the tumor enough for it to be surgically removed or for it to be removed using less invasive surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is reserved for those tumors too large for surgical removal in their current state.

- Palliative chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is considered palliative when removing all cancer cells is no longer possible. Chemotherapy can still help to relieve certain symptoms, slow down the progression of the disease, stop the disease temporarily, and avoid complications.

Dr. Sue Ettinger, AKA Dr. Sue Cancer Vet, veterinary oncologist, explains how chemotherapy for dogs isn't quite as scary as it can be for humans on DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

Cancers Chemotherapy Is Commonly Used For

Chemotherapy is indicated for treating tumors sensitive to drug therapy (such as hematologic malignancies) and for highly metastatic malignancies.

Examples include:

- Lymphomas

- Leukemias

- Multiple myelomas

- Osteosarcoma

- Hemangiosarcoma

- High-grade mast cell tumors

For solid tumors, chemotherapy is often used after the surgical removal of the primary tumor to slow any microscopic metastasis.3,6

What Happens in Dog Chemotherapy

Knowing what to expect with chemotherapy will empower you to make the best decision for your dog with cancer. So what happens when a dog gets chemotherapy?

Choosing a Protocol

Depending on a dog’s type of cancer, a specific chemotherapy protocol will be recommended. Based on published research on other patients with a similar cancer diagnosis, the oncology team will recommend the most effective treatment for that particular type of cancer.

Many different factors are considered when choosing a chemo protocol for a dog. These include:

- Finances

- Cancer type

- Cancer staging

- The number of required veterinary visits

- A patient’s tolerance of veterinary visits

- Age

- Comorbidities (other health problems)

- Possible adverse side effects

Choosing a Form of Drug

Chemotherapeutic drugs come in different forms, including oral or injectable medications. Depending on the drug, they can be given orally, subcutaneously (under the skin), intramuscularly (into the muscle), or intravenously (into a vein).2

Your veterinarian or veterinary oncologist will make the best choices for your dog’s case, cancer type, and location.

Making Sure Your Dog Can Tolerate Chemo

Routine lab work will be done before chemotherapy treatment to ensure the patient’s immune system can tolerate chemotherapy well. Other monitoring that may be performed includes:

- A urinalysis to check for infection or blood in the urine

- An electrocardiogram or echocardiogram when cardiotoxic drugs are administered

- Imaging to ensure that cancer has not spread using x-rays, MRI, or CT scan.

Once it is determined that a dog is well enough for chemo administration, proper precautions should be used to administer the chemotherapy safely.

Oral Chemotherapy for Dogs

Your veterinarian may give an oral chemotherapy pill in the hospital or send the meds with you to give at home more frequently. There are some precautions that should be taken when giving your dog oral chemo drugs. 3

- It is recommended that gloves be worn by the person administering the chemotherapy.

- Tablets should never be crushed or split.

- Chemotherapy pills should be handled in a well-ventilated area, or a respirator should be used to avoid inhalation.

Intravenous Chemotherapy for Dogs

Intravenous chemotherapy is done at the veterinary hospital only. Depending on the drug(s) your dog is receiving, the veterinary team will prepare the chemotherapy before you arrive for your dog’s appointment, or they may prepare it after you arrive.

There are many steps your veterinarian and their staff will take to get ready for your dog’s chemo appointment.

Safety

Chronic exposure to chemotherapy by those administering it can cause adverse effects and is considered unsafe. Proper safety practices must be followed. This is why these drugs are only handled and administered by trained veterinary professionals.

For intravenous chemotherapy, it is important that chemotherapeutic drugs are prepared in a biochemical safety cabinet or in a quiet room on a clean surface away from drafts.

Anyone administering chemotherapy should wear proper PPE (personal protective equipment), including a suitable mask, a chemotherapy gown, chemotherapy gloves, and protective eyewear.

The people giving chemotherapy use a lot of precautions to keep your dog and themselves safe.

Catheter Placement

Another important aspect of safe chemotherapeutic administration involves catheter placement. Several chemotherapeutic drugs can severely damage the surrounding tissues if they leak outside the vein, so precise catheter placement is necessary.

An IV catheter should only be placed in a healthy vein. If the vein has been recently used or is damaged, the catheter should be placed in a different location – this limits the risk of the drug leaking out of the vein and harming your dog’s other body tissues.2

Additional safety is achieved using closed system transfer devices (CSTDs). These eliminate the need for needles and reduce the potential for chemotherapeutic drugs to be leaked or aerosolized into the surrounding environment.

The Infusion

Once the catheter has been placed, the veterinary team will start the chemo infusion. Some drugs can be given quickly, but many must be given slowly over time to limit any side effects for your dog.

Some dogs may need to be sedated to help them stay calm during their chemo treatment, as they will need to stay relatively still during this time.

Recovery

Once the IV chemotherapy has been administered, the catheter is removed, and your dog is allowed to rest while the staff observes them.

All the supplies are disposed of per the law. And your dog is ready to go home and rest!

Veterinary oncologist Megan Duffy explains exactly what you're getting when you pay for a specialist's time and expertise on DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

How to Get the Best Results

Your oncologist and veterinary team will handle most of the logistics of chemotherapy treatment, but you also play a vital role in your dog’s care.

Here are some things you can either do yourself or approve for the veterinary care team to do to help improve the odds of your dog’s chemo treatment success.

- Get an accurate diagnosis and ensure the tumor type is known to respond to chemotherapy.

- The patient should undergo the appropriate staging tests such as thoracic radiographs, an abdominal ultrasound, a CT scan, bloodwork, etc., as indicated by the tumor type. Staging allows the clinician to evaluate the extent of the disease and may provide information that changes the treatment plan.

- The patient should be stabilized as much as possible before treatment with a chemotherapeutic agent. Although chemotherapy is generally well tolerated in veterinary medicine, if an animal is unstable or ill, the likelihood of adverse events becomes higher. Abnormalities in hydration status, electrolyte balance, kidney function, liver function, anemia, etc., should be corrected before starting chemo. However, remember that some of the patient’s medical problems will only be corrected by treating the cancer.

- Know beforehand the proposed treatment’s cost, dosing schedule, and potential toxicities. You must be committed and comfortable with the protocol for the best outcome possible. If a particular protocol isn’t feasible for you, your veterinarian can recommend a different one to better fit you and your dog.

- Explore and discuss any other treatment options thoroughly before making a decision.

- The nutritional status of all oncology patients should be assessed at the beginning of and throughout treatment. Good nutrition is necessary for the body to be able to fight cancer. Your oncologist or veterinarian may do this assessment or may recommend a consult with a veterinary nutritionist.

- Keep an open dialogue with your veterinary team to ensure that the quality of life of your dog remains the ultimate goal. Tell the vet about any side effects or challenges so the treatments can be adjusted as needed.

- Provide your vet and/or oncologist with a complete list of all medications and supplements that your dog is receiving.

Drug and Supplement Interactions

The interaction between cytotoxic drugs and most homeopathic remedies is not known.4 Therefore, your veterinarian should be consulted before giving homeopathic remedies3 or starting any new supplement.

In human medicine, antacids that contain aluminum and magnesium, antibiotics, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antifungal agents, antiretroviral agents, corticosteroids, antiemetics (Ondansetron), and herbal supplements have all been found to interact with some chemotherapeutic agents.12

Many drugs and supplements are known to interfere with chemotherapy, which is why veterinary oncologists may want to minimize their use.

This is why so many veterinary oncologists try to minimize the use of other drugs and supplements during chemotherapy treatment unless they are sure there is no interaction.

Safety and Side Effects

When dosed appropriately, chemotherapy can be administered safely. Since chemotherapy drugs do not differentiate between killing tumor cells and normal cells, following published guidelines for treatment is critical.

Most dogs tolerate chemotherapy well. Potential adverse effects include:

All of these are easily treated with supportive care or symptom management.

Bone Marrow Suppression

In rare instances, life-threatening complications related to chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression (bone marrow suppression) can develop. This requires hospitalization and aggressive supportive care.8

Organ Toxicity

Specific side effects can result from certain drugs.

For example, doxorubicin can cause cardiotoxicity or damage to the heart.

Cisplatin can cause fatal pulmonary edema in cats or renal toxicity (kidney failure) in dogs.2

The side effects are minimized by following preset guidelines about safe dosing and administration.

Careful home practices are important to keep you and your family safe while your dog is on chemotherapy.

Harm to Humans

Chemotherapy can also be mutagenic and carcinogenic, posing a public health risk if incorrectly handled.1 Safety measures that should be observed include the following:

- Strict adherence to published guidelines regarding personal protective equipment (PPE) worn by individuals administering chemotherapy.

- Immunocompromised individuals and women who are pregnant or breast-feeding should avoid working with chemotherapeutic agents.3

- No food or drug should be in the chemotherapy administration room.

- Once the drug is administered, all chemotherapy waste, such as syringes, IV catheters, bandages, etc., should be returned to the sealed plastic bag and disposed of with other biohazardous waste according to government regulations. Chemotherapy waste should not be thrown into the sharps container or garbage.

- A protocol and supplies (spill kit) for cleaning up hazardous materials should be readily available should a spill occur.2

- Since patients excrete potentially harmful drugs and their metabolites into urine, feces, vomit, and saliva for variable periods following injectable or oral chemotherapy administration, food bowls and bedding should be washed separately if accidents occur. After receiving cytotoxic drugs, dogs should be encouraged to urinate and defecate on a separate area of grass.4

- Owners should wear gloves when cleaning up after their dogs for up to 72 hours after intravenous drug administration and wash the area with diluted bleach.2

Home Care After Dog Chemotherapy

There isn’t usually much home care needed after a chemotherapy treatment, as side effects are less common thanks to the lower doses used for veterinary patients.

Although adverse reactions and side effects are less common in animals receiving chemotherapy, some animals experience gastrointestinal upset. Therefore, medications may be prescribed to prevent nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting and to improve appetite. Food should also be palatable to encourage your dog to eat full meals.3

The “just in case” drugs your oncologist sends home should be used proactively, “just in case” your dog is stoic and doesn’t reveal how sick they feel.

Keep in mind that dogs can be stoic, and they may not always “act sick.” If your oncologist sends you home with medications for digestive upset, it is better to give them even if you don’t think your dog needs them, just in case, for a few days after chemotherapy.

Follow-Up

Regular follow-up will be needed depending on the diagnosis and treatment plan. Some tests may be repeated weekly to ensure that your dog tolerates and responds to the treatment, while other tests will be done less often.

At the very least, patients should be seen regularly for hematological monitoring (bloodwork).4

- A complete blood count ensures an adequate white blood cell count.

- It is generally accepted that an absolute neutrophil count of greater than 2000 cells per microliter and greater than 50,000 platelets per microliter should be present before chemotherapy administration to minimize the risk of sepsis or other complications.8

Tests such as an echocardiogram and an EKG can screen and monitor patients being treated with doxorubicin to ensure their heart is functioning normally.6

A chemistry panel is performed routinely to evaluate kidney and liver function since these organs are necessary for metabolizing various chemotherapeutic drugs.

Because sterile hemorrhagic cystitis is a risk with cyclophosphamide, urine should be monitored with periodic urinalysis.3

When calculating costs, be sure to include follow-up tests before, during, and after your dog’s chemotherapy protocol.

Even if your dog is getting chemotherapy from an oncologist, follow-up appointments and testing can often be done through your regular veterinarian.

When to Not Use Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is not appropriate for every cancer or for every patient.

The veterinary team can access peer-reviewed published studies demonstrating appropriate and efficacious cancer treatment plans. These studies should guide treatment decisions. If your dog’s cancer type does not respond to chemotherapy, it is probably not worth the financial cost or the risk of side effects to give it anyway.1

Dogs with impaired liver and kidney function may not be eligible for chemotherapy, or may need lower doses.

Many chemotherapy drugs are metabolized and eliminated by the liver and kidneys, so animals with pre-existing renal or hepatic disease may experience increased toxicity or decreased efficacy. Dosages may need to be adjusted in these patients.6

Risk versus benefit should always be considered. Ask your practitioner for details on how a chemo protocol has been performed in dogs with the same cancer as yours, what risks are involved, and how much time you will gain by pursuing treatment.

Where to Get Chemotherapy for Dogs

General practice veterinarians with extensive oncology and chemotherapy safety knowledge can administer chemotherapy.

Still, referral to a specialist may be appropriate if the primary care veterinarian or you wish to consider all possible treatment options, or when the referring veterinarian cannot provide optimal treatment for any reason.3

The best outcome occurs when general practice veterinarians and oncologists can collaborate with the mutual goal of the patient’s well-being.

Dr. Kristen Lester explains how general practice veterinarians can offer chemotherapy to their clients on DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

The Cost of Chemotherapy for Dogs

According to the Veterinary Cancer Society, dog chemotherapy costs can vary between $150-$600 (or more) per dose.15

The veterinary team should discuss the cost of treatment with you and receive consent before proceeding.

The fee will certainly depend upon the drug used, the route of administration, the size of your dog, and what costs are in your location.

It is important to understand that there are many published protocols for cancer treatments and dogs. It will be up to the veterinary team to discuss treatment costs and support the plan that makes the most sense for each patient.

In some cases, cancer treatments can cost as much as $10,000 in total. These costs are often spread out throughout treatment after the initial diagnosis.16

Keep in mind that in addition to financial costs, there are time and energy costs, as well. Work with your veterinarian to find the right balance and budget for you and your dog.

- Stephens T. The Use of Chemotherapy to Prolong the Life of Dogs Suffering from Cancer: The Ethical Dilemma. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI. Jul 14 2019;9(7).

- MacDonald V. Chemotherapy: managing side effects and safe handling. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne. Jun 2009;50(6):665-668.

- Biller B, Berg J, Garrett L, et al. 2016 AAHA Oncology Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. Jul-Aug 2016;52(4):181-204.

- Hayes A. Safe use of anticancer chemotherapy in small animal practice. In Practice. 2005;27(3):118-127.

- Carrick S, Parker S, Thornton CE, Ghersi D, Simes J, Wilcken N. Single agent versus combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Apr 15 2009;2009(2):CD003372.

- McKnight JA. Principles of chemotherapy. Clinical techniques in small animal practice. May 2003;18(2):67-72.

- Lee JJ, Liao AT, Wang SL. L-Asparaginase, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisolone (LHOP) Chemotherapy as a First-Line Treatment for Dogs with Multicentric Lymphoma. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI. Jul 26 2021;11(8).

- Burgess KE. Lymphomas. Clinical Small Animal Internal Medicine2020:1231-1239.

- Rassnick KM, Bailey DB, Malone EK, et al. Comparison between L-CHOP and an L-CHOP protocol with interposed treatments of CCNU and MOPP (L-CHOP-CCNU-MOPP) for lymphoma in dogs. Veterinary and comparative oncology. Dec 2010;8(4):243-253.

- Brown PM, Tzannes S, Nguyen S, White J, Langova V. LOPP chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for dogs with T-cell lymphoma. Veterinary and comparative oncology. Mar 2018;16(1):108-113.

- DiBernardi L. Approach to the Cancer Patient. Clinical Small Animal Internal Medicine2020:1197-1204.

- Scripture CD, Figg WD. Drug interactions in cancer therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer. Jul 2006;6(7):546-558.

- Smith AN, Klahn S, Phillips B, et al. ACVIM small animal consensus statement on safe use of cytotoxic chemotherapeutics in veterinary practice. Journal of veterinary internal medicine. May 2018;32(3):904-913.

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. How does chemotherapy work? [Updated 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279427/

- FAQs (no date) Veterinary Cancer Society. Available at: http://vetcancersociety.org/pet- owners/faqs/ (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Williams, C. (2019) Understanding (and paying for) the cost of cancer treatment for your pet, Pet Care Blog – Dog and Cat Health Advice and More | Healthy Paws. Available at: https://blog.healthypawspetinsurance.com/cost-of-cancer-treatment-for-your-pet (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.