The dog's immune system and the human immune system are very similar, and we share similar environments. Can we use the immune system to fight cancer? Yes, but it's not quite as simple as "immune boosting." Let's get an overview of the immune system, its many different pieces, and how they work together to help your dog fight everything from the sniffles to cancer.

Key Takeaways

- Supporting a healthy immune system is important to your dog’s health whether they have cancer or not. A balanced diet, exercise, a clean environment free of bacteria and viruses, limiting exposure to viruses and bacteria outside the home or from other animals, the wise use of supplements (without overuse!), and reducing stress, in general, all support immunity.

- Cancer attacks the body in many ways, and one of the main methods is by attacking or hijacking your dog’s immune system. Dogs with cancer probably have weakened immune systems (otherwise they would not have cancer). Other causes of a weak immune system include genetic problems, bacterial infections, and viral infections. Recurrent infections usually indicate a compromised immune system.

- In addition to cancer itself suppressing the immune system, cancer treatments like chemotherapy may also suppress the immune system.

- Omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and probiotics are generally accepted as helpful in providing immune support. However, it’s important to balance their use so they don’t interfere with other therapies.

- While a healthy dog’s immune system is vibrant and strong, even healthy dogs cannot always fight off every bacteria, virus, or cancer without our assistance. If a dog is already sick and immune-compromised, restoring their immune system to full health may not be possible. Even if possible, the immune system alone might not be enough to battle a foe like cancer, parvo, heartworm, or other devastating illnesses and infections.

An Overview of the Immune System’s Two Parts

The dog’s immune system is complex and challenging to explain in simple terms. This article will help you understand the basics of dog immunity and how it applies to dog cancer.

The immune system is divided into two parts: innate (non-specific) and adaptive (specific).

- The innate immune system works through a system of barriers and non-specific cells that kill any microscopic foreign invaders.

- The adaptive immune system works by learning specific details of foreign invaders (antigens) and developing cells that can target those specific antigens.2

The innate immune system is always the first line of defense between your animal and the outside world. Bacteria and viruses will encounter the innate immune system first when trying to invade.

If a foreign substance manages to evade the innate immune system, it will then encounter the adaptive immune system, which, although slower to act, is capable of producing armies of cells that can specifically target and eliminate these pathogens.

White Blood Cells Are Immune System Cells

It’s common in cancer to hear talk about white blood cells. That’s because the immune system is composed of various white blood cells, and when your veterinarian talks to you about your dog’s white blood cell count it is a measure of immune function.

They are called the white blood cells (WBC) due to their appearance in a test tube when blood is spun down in a centrifuge. When dogs get certain bacterial, viral, or parasitic infections there is a corresponding increase in white blood cells to fight the infection.2

How the Innate Immune System Works

Almost every living organism possesses an innate immune system. You could think of the innate immune system as a kind of living structural protection. If the body were a castle, the innate immune system would be the moat, the drawbridge, and the tall, thick stone walls.

Several types of white blood cells make up the innate immune system:

- A majority of the white blood cells that participate in the innate immune system are the “phils”: Neutrophil, Eosinophil, and Basophil.

- There is also a lymphocyte or lymph cell called the Natural Killer (NK) cell which is a part of the innate system and is effective against viruses and active in fighting cancer.

- Another type of white blood cell, macrophages, live in tissues and engulf foreign invaders as well as playing a role in tissue repair and homeostasis.

- And finally, dendritic cells bind with foreign antigens (foreign invaders).

For dogs, the innate immune system includes their skin, saliva, mucous membranes, the “phils,” NK cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.

Let’s consider a bacterial cell trying to invade a dog and all the different ways the innate immune system protects the dog from that bacterial cell:

- The first problem or barrier the bacteria will encounter is the skin. Without a cut or scrape it cannot get past it.

- If the dog eats something with bacteria on it, there are substances present in the saliva and in the stomach acid that will kill the bacteria.

- Even in the respiratory tract there are tiny hair like structures and mucus that trap foreign particles and cells and dispose of them.

- If the bacterial cell is able to survive this gauntlet, it will be met by a macrophage or the “phils.” These white blood cells possess potent chemicals to degrade and destroy foreign microbes.

How the Adaptive Immune System Works

If a foreign invader (also called an antigen) is able to get past all these innate immune system mechanisms and gain access to the body, it will be detected by the adaptive (specific) immune system.

While slower to respond, the adaptive immune system is more specific than the innate immune system. If the body were a castle, the adaptive immune system is like the soldiers inside the walls. They are able to kill the invaders who have scaled the castle walls using a variety of weapons, but they first must find and target each invader.

First, macrophages or dendritic cells (innate immune cells) pick up the foreign invader (antigen) and present it or hand it off to one or more of the adaptive cells.

These adaptive immune cells include T-cells and B-cells. Once activated, T and B cells begin making very specific products to defeat the foreign invader.

- B-cells produce antibodies which bind and neutralize antigens.

- T-cells make two difference cell types: “Helper” T-cells which help stimulate the immune system, and “Killer” T-cells which can directly target and destroy antigens.

T and B Cell Activity

When they are activated, T and B cells rapidly divide, effectively creating an army of cells designed to fight a very specific invader.

Under normal circumstances, the army of cells defeats the foreign invader, and then the excess T and B cells die off.

Among this increased population of T and B cells also exist “memory” cells which have a longer lifespan compared to the soldier T and B cells. These memory T and B cells “remember” the foreign invader and how to kill it. They provide continued protection to the dog throughout life.3

If the foreign invader ever returns, the memory cells will produce another army of T and B cells to destroy the antigen, this time much faster than the first time the antigen was encountered.

Four Types of Immunity

There are four subcategories or types of immunity: Active Immunity, Passive Immunity, Natural Immunity, and Artificial Immunity.

Active Immunity

Active Immunity is when a healthy dog receives an immune stimulus (antigen) and has a healthy and normal immunological response (described above) that produces long-term memory cells to protect the dog throughout its life.

Active immune responses can happen if your dog encounters an illness in their environment, is sick for a short time, and then gets better. The dog will be afforded long-term protection against the antigen that provoked the active immune response.

Passive Immunity

Passive Immunity is when a dog does not generate an immune response of their own, but receives immune substances from outside the body.4 The most common example is when veterinarians administer antibodies directly to dogs to treat different issues. The antibodies enter the body, bind to the antigen, the disorder resolves, and the dog metabolizes the antibodies and clears them from the system. There is no long-term protection or “memory” formed to protect the dog again at a later date.

One of the most common passive immune treatments is the treatment of snake venom. Dogs are given an antibody against the venom that is usually developed in horses. The antibody neutralizes the venom, the dog metabolizes the venom/antibody complex out of the body safely but will not retain any long-term protection against the venom. If the dog is bitten by a snake later, they will need another venom antibody injection to combat the snakebite.

Natural Immunity

Natural Immunity is achieved when an immune response is provoked without medical intervention. This would occur with something like canine influenza. A dog could encounter influenza, have a response including fever, respiratory, or gastrointestinal symptoms, and once resolved the dog will carry an increased number of T and B “memory” cells to protect it from catching that strain of canine influenza again.

Because there can be no medical intervention, natural immunity will only occur through active means.

Artificial Immunity

Artificial Immunity occurs when a medical procedure is used to aid in immunity.

A common example of artificial immunity is vaccines. Vaccines are usually weakened or destroyed antigens such as viruses and bacteria. Once injected into the dog, the immune system forms an active response which results in “memory” T and B cells, but because the bacteria and viruses were weakened or dead there are fewer to no symptoms that would occur if the dog had encountered the antigen naturally (such as fever, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea).

Artificial and Natural Immunity can produce the same immune response and afford the same long-term protections.

Immune Development Can Come from Multiple Sources

Immune activity is complex and can occur in different combinations and through different means.

Active Immune responses can happen through both natural and artificial means. For example, a dog could encounter a disease in its environment (and gain natural immunity) and also get a vaccine for that disease (and gain artificial immunity).

Passive immunity occurs through artificial means in most cases (like anti venom), but there are exceptions. For example, the colostrum (mother’s milk) that is passed from bitches to pups contains antibodies to protect the puppies from antigens in the environment.

This is considered Natural Passive Immunity, because it comes from the body, not from medicine, and comes from the mother, not the pup’s own system. The antibodies a puppy gets from its mother will die off as the puppy matures and develops its own immune system.

Signs of Immune Deficiencies

Sometimes the immune system is compromised, and we call that immune deficiencies. Immune deficiencies can occur at birth (primary or congenital) or be acquired after birth (secondary).

Most immunodeficiencies affect a particular white blood cell type and its ability to function normally.7 Both innate and adaptive immune cells can be affected.

- The distemper virus causes the most common immunodeficiency in dogs. The distemper virus kills T-cells and B-cells, also known as lymphocytes.8 The more severe the infection, the more lymphocyte destruction is occurring.

- Parvovirus, which is predominantly seen in puppies, also depletes the number of white blood cells in dogs.9

When innate or adaptive immune cells are compromised or depleted for any reason, the dog has a harder time warding off common bacteria and/or viruses it might encounter in its environment. Reoccurring infections can occur as a result.

A symptom of all immune deficiencies is reoccurring infections. Dogs will exhibit symptoms such as upper respiratory or gastrointestinal distress. Your vet will treat the problem, but when the treatment, such as antibiotics, is complete the symptoms will return. This is a sign of immune compromise of some sort.

A common blood test like the complete blood count (CBC) can help to reveal the numbers of white blood cells in the dog’s immune system. There are also additional tests that can be run to check immune cell products like antibodies. A deficient immune system has a harder time finding and killing cancer cells as they develop.

The Immune System and Cancer Development

The immune system can find and kill cancer cells early in their lifespan. However, it’s a particularly tricky disease in any species because cancer forms from inside the dog’s own cells. Cancer is not a foreign invader like bacteria or viruses that can be easily identified by the immune system. Cancer is the dog’s own cells that have suddenly begun to rapidly divide and can subsequently invade other tissues and even travel to other parts of the body.5

But even though cancer isn’t technically foreign, there are still signals to the immune system that something is wrong, and these rapidly dividing cells should be destroyed.

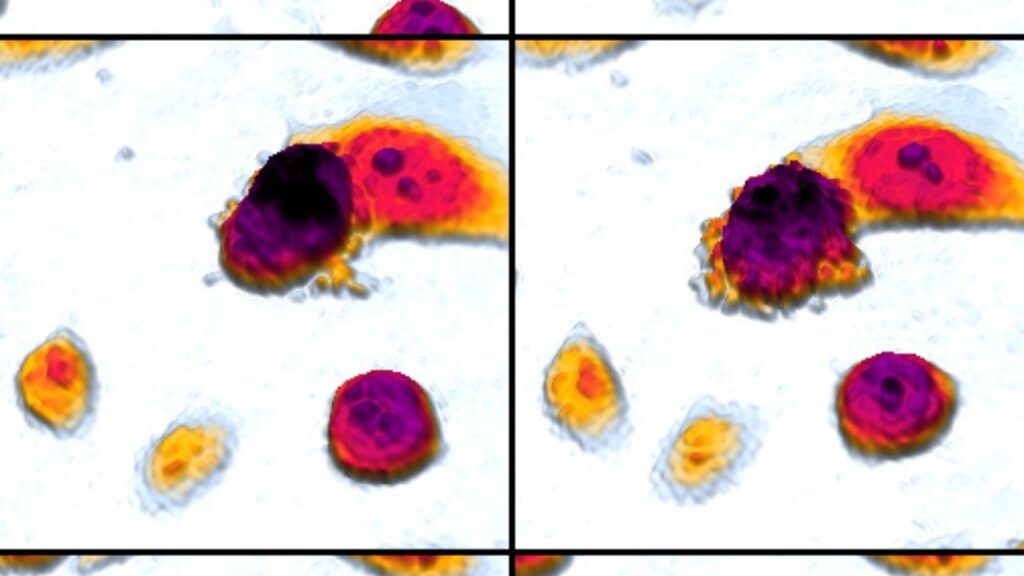

Natural Killer (NK) cells and T-cells are two of the most adept immune cells at recognizing cancer. To grow at an accelerated rate, cancer cells will frequently overproduce and/or mutate certain cellular proteins needed for growth. When these proteins are expressed on the cell’s surface, they will be detected by the immune system as abnormal and eliminated by the dog’s own immune system.

Isn’t the Immune System Able to Kill Cancer Without Help?

Once cancer has evaded the immune defenses outlined above, it is uncommon for the immune system to kill an established tumor. If your dog has been diagnosed with cancer, it is unlikely that the dog’s immune system will resolve the issue. Medical intervention may be necessary. Not only does cancer occur from the body’s own cells, but some types of cancer have even developed mechanisms for evading the immune system 6.

The Immune System During Cancer Treatment

Cancer is a rapidly dividing cell type in the body, and traditional cancer treatments like radiation and chemotherapy specifically target rapidly dividing cells to shrink and even eliminate tumors.

However, there are several other rapidly dividing cell populations in the body that are necessary for a healthy immune system. Both red blood cells and white blood cells (the immune cells) rapidly divide within the bone marrow.

Unfortunately, chemotherapy and radiation will reduce the proliferation of every rapidly dividing cell population, including these necessary cell types. In short, chemotherapy and radiation may actually reduce the functioning of your dog’s immune system. It is important to keep immune function in mind when caring for your dog during these treatments. Your veterinarian and oncologist will keep an eye on your dog’s immune system by running tests to look at the white blood cell counts.

Your veterinary team may also choose to delay vaccinations or other treatments until chemotherapy is complete so as not to overload your dog’s immune system. This may vary from case to case, so talk to your veterinarian or oncologist if your dog is due for any vaccinations during chemotherapy treatment.

Using Immunotherapy

In recent decades, immunotherapies for cancer have increased. Most immunotherapies increase the natural immune responses against cancer that have been discussed here.

For example, certain treatments can “hypercharge” immune cells and their ability to recognize and eliminate cancer cells.

In some treatments there is an antigen associated with the specific type of cancer, and by artificially injecting that antigen into the patient, we can help train and strengthen the immune system to attack not only that antigen, but the cancerous cells themselves.6

There is an ongoing cancer vaccine trial (VACCS) which hopes to prove a new cancer vaccine can help prevent multiple types of cancer in dogs.

Dr. Jenna Burton explains how the VACCS trial is developing in this episode of DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

Supporting a Healthy Immune System

Whether your dog has cancer or not, supporting her immune system is important. Fostering and supporting a healthy immune system in your dog starts at home. Many of the strategies employed for healthy human immune systems can also help dogs who suffer from immune disorders or who are undergoing cancer treatments like chemotherapy or radiation. There are many ways to support the immune system:

- Balanced Diet – A healthy and balanced diet free from excessive chemicals and preservatives can help increase the overall health and immune function of your dog. Dogs are omnivores, and a balanced diet includes both plant and animal sources. Healthy Omega-3 Fatty Acids have been shown to have a link to immune function10 and can easily be made a part of your dog’s diet.

- Exercise – All dogs should have a regular exercise regimen appropriate for their breed, age, and health. Speak to your veterinarian about what might be appropriate for your dog. Exercise can help your dog’s physical and mental health.11

- Cleanliness of environment – All dogs, but especially those facing immuno-compromised health conditions, can benefit from a clean environment. Where your dog eats, sleeps, and plays should be monitored and regularly cleaned to reduce the number and amount of bacterial or viral pathogens the dog(s) could be exposed to.

- Consider the number of other animals your dog might come into contact with within their environment – not just other dogs, but wild animals, birds, and other pet animals. These are all potential sources of foreign bacteria and viruses.

- Supplements – There are a multitude of supplements available for dogs. Some of the largest and most widely accepted are Omega-3 Fatty Acids10, Antioxidants12, and Probiotics13. Dogcancer.com has an entire section dedicated to supplements where you can learn about them in-depth. Always speak with your veterinarian before starting a supplement for your dog.

- Reduce Stress – Dogs experience stress just like humans do. Excessive stimulation in the form of noise, light, smells, or strangers can all cause stress in animals. Chronic stress can negatively impact the immune system function,14 and has even more implications if your dog is battling cancer.15 It’s not always easy to eliminate stress, but your veterinarian or a veterinary behaviorist can help address stress in your dog.

- Regular veterinary visits – Having an annual checkup with your veterinarian is paramount to maintaining your dog’s health. Often early warning signs can be caught during regular exams and tests. If your dog has a diagnosed condition that requires a specialist, it is important to maintain regular contact with them.

- Weintraub A. Dogs’ Immune Systems Are Much Like Ours And That’s A Boon To Cancer Research. Forbes. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/arleneweintraub/2017/09/14/dogs-immune-systems-are-much-like-ours-and-thats-a-boon-to-cancer-research/?sh=e9b0ac918330

- Immune System Responses in Dogs – Dog Owners. Merck Veterinary Manual. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/dog-owners/immune-disorders-of-dogs/immune-system-responses-in-dogs

- Adaptive Immunity in Animals – Immune System. Veterinary Manual. https://www.msdvetmanual.com/immune-system/the-biology-of-the-immune-system/adaptive-immunity-in-animals

- Passive Immunization in Animals – Pharmacology. Merck Veterinary Manual. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/pharmacology/vaccines-and-immunotherapy/passive-immunization-in-animals

- National Cancer Institute. What Is Cancer? National Cancer Institute. Published May 5, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

- Messerschmidt JL, Prendergast GC, Messerschmidt GL. How Cancers Escape Immune Destruction and Mechanisms of Action for the New Significantly Active Immune Therapies: Helping Nonimmunologists Decipher Recent Advances. The Oncologist. 2016;21(2):233-243. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0282

- Primary Immunodeficiencies in Animals – Immune System. MSD Veterinary Manual. https://www.msdvetmanual.com/immune-system/immunologic-diseases/primary-immunodeficiencies-in-animals

- Schobesberger M, Summerfield A, Doherr MG, Zurbriggen A, Griot C. Canine distemper virus-induced depletion of uninfected lymphocytes is associated with apoptosis. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2005;104(1-2):33-44. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.09.032

- Goddard A, Leisewitz AL. Canine Parvovirus. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 2010;40(6):1041-1053. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.07.007

- Gutiérrez S, Svahn SL, Johansson ME. Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Immune Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20):5028. Published 2019 Oct 11. doi:10.3390/ijms20205028

- Jones AW, Davison G. Exercise, Immunity, and Illness. Muscle and Exercise Physiology. 2019;317-344. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-814593-7.00015-3

- Carr AC, Maggini S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):1211. Published 2017 Nov 3. doi:10.3390/nu9111211

- Zhang Z, Tang H, Chen P, Xie H, Tao Y. Demystifying the manipulation of host immunity, metabolism, and extraintestinal tumors by the gut microbiome. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4:41. Published 2019 Oct 12. doi:10.1038/s41392-019-0074-5

- Dantzer R. Neuroimmune Interactions: From the Brain to the Immune System and Vice Versa. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(1):477-504. doi:10.1152/physrev.00039.2016

- Zhang L, Pan J, Chen W, Jiang J, Huang J. Chronic stress-induced immune dysregulation in cancer: implications for initiation, progression, metastasis, and treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10(5):1294-1307. Published 2020 May 1.

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.