EPISODE 212 | RELEASED April 17, 2023

Does Plastic Cause Cancer in Dogs? | Dr. Charlotte Hacker

Did you know that plastic breaks down over time, leaching chemicals that can cause cancer? Your dog may be at risk from plastics in your home.

SHOW NOTES

Plastic was a wonder material. It makes our lives easier, and can be produced synthetically without depleting natural resources like elephants or camphor trees. But some of the very qualities that make plastic amazing also make it potentially harmful.

Dr. Charlotte Hacker, PhD is a wildlife biologist who researched the connection between plastic and cancer for an article on DogCancer.com. In this episode she talks about several of the harmful chemicals that can be in plastic or produced during the manufacturing of plastic products. She also explains what we currently know about how different chemicals can impact the endocrine system in your dog’s body and the environment at large.

But don’t panic. Even though it is pretty much impossible to completely avoid plastic, there are easy strategies you can take to minimize potentially harmful plastic exposure for your dog.

[00:00:00] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Plastics are so ubiquitous and pretty much unavoidable. Even if you buy something that’s not plastic, it probably came in plastic packaging. Yeah, so there is kind of this element of helplessness and hopelessness in terms of, you know, dealing with these things.

[00:00:16] >> Announcer: Welcome to Dog Cancer Answers, where we help you help your dog with cancer.

[00:00:23] >> Molly Jacobson: Hello, friend. I’m Molly Jacobson, and today on Dog Cancer Answers, we’re looking at a known carcinogen that can play a role in causing cancer: plastic. Our guest is Dr. Charlotte Hacker, a wildlife biologist and science writer who’s been researching plastic for an article on our website, dogcancer.com.

We’ll talk a little bit more about your background in a minute, but first, I just wanna welcome you to Dog Cancer Answers, and thank you for all of the work you’ve been doing on behalf of dogs with cancer and the people who love them.

[00:00:53] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, of course. Thank you for having me. This is a job I’m really passionate about doing and excited I get to be on the podcast now as well.

[00:00:59] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah, it’s really great to talk to you because you have such a clear-minded view of science for many, many reasons, and so much great experience in animals and wildlife and genetics, cancer. And so you wrote this really interesting article about plastics that, frankly, terrified me. You know, we asked you to write it and then, and then I read it and I thought, oh my goodness.

I’m so glad we switched all of our plastic things to glass a couple years ago. I feel so much better about my health already just after reading that. So, my first question is, should we panic about how much plastic is in our lives?

[00:01:45] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Plastic is such a, a double-edged sword, right? Because it’s so convenient. It’s made things a lot easier, and it’s pretty much impossible to avoid nowadays.

[00:01:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah.

[00:01:56] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: You know, but then we’re hearing, on the other hand, it’s, it’s evil, it’s bad, you know, you need to cut it out of your life. And, and I think what’s really scary about plastic is just some of the chemicals that are involved. And it’s better than it used to be. There’s not as many scary things or not as much of scary things.

[00:02:12] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:02:13] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: That go into plastic, but.

[00:02:14] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s good.

[00:02:15] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: It’s still definitely something to be mindful of, and with all the alternatives, it can be pretty simple to switch some of these things out and try to minimize your plastic use in general, not just for the environment, but for your own health.

[00:02:29] >> Molly Jacobson: Let’s talk a little bit about those chemicals that are in plastics that we should be concerned about, that scientists like you are concerned about.

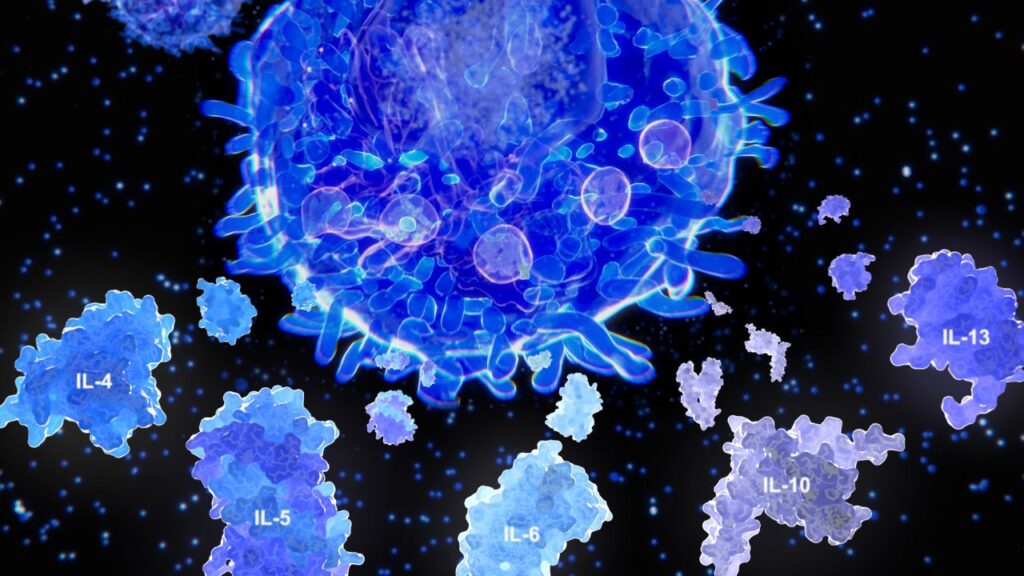

[00:02:37] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So one of the top ones that you’ve probably heard about is Bisphenol A, BPA for short. Um, that’s kind of the one that gets talked about the most because it was once really, really prevalent in plastics and still is to a certain degree. It’s responsible for making plastic hard and clear. So you can imagine how many things it’s been used in, when we think of plastic, we usually think of the clear, hard plastic. But unfortunately, with BPA, it’s known to interfere with the normal functioning of your hormones. So this is a chemical that’s called an endocrine disruptor.

And you know, you have the endocrine system in your body. Your dog has an endocrine system as well. And that endocrine system is, um, responsible for kind of pumping out and reading and producing hormones. And you can think of hormones as, I like to think of them as kind of little messengers that are constantly running throughout the body, and they’re basically telling your body what it needs to do and when.

So every molecule, every cell in your body has a job, and hormones are responsible in some capacity in almost every function of those. And so when you have a chemical like BPA introduced into the body, and the body thinks that it’s a hormone, because BPA in and of itself is mimicking a hormone.

[00:03:52] >> Molly Jacobson: Ah.

[00:03:52] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: It’s going to disrupt the other functions that would normally be going on in the endocrine system and ultimately affect biological functions. It can affect things like proper development. And so BPA has really kind of become the one that’s most talked about, I think, because it is, you know, it can have large scale effects with even small doses. And it’s in, you know, it’s, it’s pretty much in everything it seems like.

[00:04:17] >> Molly Jacobson: What is it commonly found in, BPA?

[00:04:19] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So a lot of it, polycarbonate plastic as well as epoxy resin, but it’s in things like the lining of food cans. So like your dog’s food. Or the food that you eat, vegetables that might be in a can. The thing that prevents that metallic taste from seeping into your food is, you know, a layer of something that might be kind of within that can itself.

And you’ll even see now, you know, a lot of cans will say "made without BPA lining" or something like that, and that’s great, right? You as a consumer might think, good, I’m gonna take that off the shelf. I’m gonna buy that one over this other brand. But what you might not notice at first is there’s always this, there’s usually this little asterisk right next to, you know, no BPA in the lining. And that asterisk actually on the back will tell you that there’s no BPA intentionally added.

[00:05:12] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh no.

[00:05:13] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So as per regulations in the United States, you can’t intentionally add a lot of these chemicals that are in plastics, but they still show up. They still happen. They can still be a part of that, that process and still be detected. And so even if you think you’re buying something that is BPA free, you still wanna be mindful that it might not actually be 100% BPA free.

[00:05:33] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow. I’m glad to know what that asterisk means. We didn’t put any BPA in here.

[00:05:40] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, yeah. Basically.

[00:05:41] >> Molly Jacobson: But we didn’t necessarily remove any BPA that was already present.

[00:05:46] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Sure, yeah. That’s essentially what it’s saying. Yeah.

[00:05:48] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:05:49] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And it’s in very small, tiny print. You know, it’s hard to miss unless you’re kind of looking for it. And I think we as consumers are just wanting to make these easy switches, and so we buy into that, right? We buy into that label, and then are kind of misled a bit.

[00:06:01] >> Molly Jacobson: So the BPA was originally used and is maybe not taken out now because it basically puts a little plastic lining over the metal of the can and that would mean that the metal of the can doesn’t eventually, over time, sort of dissolve and start to give you that metallic taste that you can get in plenty of food. I remember that taste very well from my childhood. So it sounds like there’s a good intention behind plastic’s use in this case, but the consequences – do you think they knew that this was an endocrine disruptor when they first started using BPA?

[00:06:38] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Plastic has, in and of itself, a really interesting history, and we can get into that if you want to, but I, I think in the beginning, BPA was, you know, plastic really had this fast rise in terms of it going to a consumer market. And whether or not those chemicals were actually adequately tested or you know, whether in a lab those manufacturers are looking at that, you know, I’m not really sure.

[00:07:02] >> Molly Jacobson: Uh huh.

[00:07:03] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But what we have seen in general is a lot of diseases associated with the endocrine system that have spiked and that spike has coincided with the use of plastics being more and more ubiquitous, kind of, in our daily lives. And so they may have known, they may not.

[00:07:19] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:07:19] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But there’s definitely been evidence along the way that it’s been a problem.

[00:07:23] >> Molly Jacobson: So like what kind of diseases? I know there are several cancers that are driven by endocrine, are endocrine system cancers or are sensitive to hormonal changes in the body. So I imagine that’s one category of disease, and what else?

[00:07:37] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, you’re, you know, any, like you just said, breast cancer, you know, all sorts of cancers of endocrine functioning organs. But a lot of developmental issues. So, you know, hormones are playing a big role during development. They’re kind of in overdrive in a lot of ways. And development’s really this critical time period for things to kind of get up and running.

You can almost think of it as like, you know, your, your body’s going through all of these changes, and especially in utero, and if you’re having all of those endocrine disruptors floating around in there, even if you’re in the womb, right, you’re not in this super protected environment because you’re kind of getting whatever mom is getting.

And so developmental, or diseases that are kind of part of things that go wrong during development in utero, are a really big concern with a lot of these chemicals specifically because they’re just interfering with natural processes and then, you know, with that you have things not quite going according to plan if, if those chemicals were not present.

[00:08:33] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So that sounds like a lot of problems that we’ve seen. Yeah. A lot of spikes in developmental issues in children.

[00:08:40] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. And a lot of weird things like allergies have been linked.

[00:08:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow.

[00:08:44] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: To having some of these chemicals or exposure to some of these chemicals, which is, you know, something people can live with, but other times allergies are very severe and life-threatening. And so it kind of runs a wide spectrum of possible outcomes.

[00:08:58] >> Molly Jacobson: Crazy. Okay, so more than one reason to try to eliminate BPAs. What’s another chemical that we are concerned about in plastics?

[00:09:09] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: There’s a broad group of chemicals that are commonly known as plasticizers. And they’re things like, phthalates is a big group and alkylphenols are a big group, and they’re essentially chemicals that make plastic easier to work with. They make it more moldable, it can be thinner, it can work into more flexible shapes. And it’s found in a lot of things, personal care products like shampoos even have them, which is kind of, you know, bizarre to think about. Um, and, uh, flooring.

[00:09:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Why do you need plastic in your shampoo?

[00:09:46] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: I know it’s kind of scary, right? It’s like, why? Why do we need that, you know? But at some point along the manufacturing process that gets in there, and there are.

[00:09:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Did you say flooring?

[00:09:55] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Flooring, like flooring, like on the floor, construction material, that kind of thing. Yeah.

[00:10:01] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, like all of the laminates.

[00:10:03] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So it’s in your house.

[00:10:04] >> Molly Jacobson: It’s in your house.

[00:10:05] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes. And there are several types of phthalates, for example, that are considered restricted substances under the United States Consumer Products Safety Improvement Act. It’s a mouthful. And others are considered substances of high concern in countries like Japan and in the European Union. And so we know for sure that they’re, you know, they’re also considered endocrine disruptors, just like BPA is.

[00:10:31] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:10:31] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And that they are, you know, ones that we wanna be worried about.

[00:10:35] >> Molly Jacobson: And that’s, can you spell it and say it again? Phthalates.

[00:10:40] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: It’s phthalates.

[00:10:42] >> Molly Jacobson: Phthalates.

[00:10:42] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But it’s P H T H A L A T E S.

[00:10:48] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. I’m not gonna attempt it. I’m gonna let it sit there and we’ll, we’ll make sure it’s spelled correctly in the show notes. It’s definitely correct in our article on dogcancer.com.

[00:10:59] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes. Yeah. Yeah. A lot of these are difficult to pronounce.

[00:11:05] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah.

[00:11:06] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Which I think is also why, you know, we skip over – you know when we look at ingredients and we kind of skip over the things, we’re like, what is that? You know, not realizing that it might not be something that’s great for us.

[00:11:16] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah, I imagine that this ingredient, the flat, flat, phthalates, flat, uh, I’m not saying it right.

[00:11:22] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Phthalates?

[00:11:23] >> Molly Jacobson: I imagine this ingredient that creates like a plasticizing effect would make like a personal care product feel nice. I can see that kind of slippery, you know, plastic has such a, it is a sensual pleasure in a way to touch plastic. It feels good often. I mean, depending on, I guess, how well made a plastic, I don’t even know if that’s the right way to say it, depending on the plastic. But I can imagine that in a, in a shampoo, I guess maybe it would give some slip or it would make it feel more luxurious under your fingers or, but I can’t, I can’t see if I saw that on a label and I knew that meant plastic, I don’t know that I’d buy that shampoo.

[00:12:09] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, that would definitely, I’d rather have less luxurious feeling.

[00:12:12] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. The point is clean hair.

[00:12:14] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And safer shampoo. Yes, exactly. Yeah.

[00:12:18] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow. What else are we concerned about?

[00:12:21] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Um, let’s see here. Lead. Lead is sometimes added to plastics.

[00:12:26] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, lead?

[00:12:27] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes. It’s definitely not as common as it used to be, but it has not been banned necessarily altogether. You know, we know that there are dangers to lead exposure and, you know.

[00:12:39] >> Molly Jacobson: Ugh. That’s so disappointing.

[00:12:41] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, lead is a tough one because it was historically used in so many things, and you know, we know what the outcomes can be of exposure to lead, especially for children. But it is something that was once added to products that would make them easier to work with and ultimately make them stable for longer periods of time. So kind of extending, I guess, the shelf life, if you wanna think of it, of plastics. Because plastics do degrade over time, which is part of the big problem, right?

‘Cause as they degrade, these chemicals are leaching out and that’s where a lot of the danger comes from. And lead has been, and you know, may still be in some of those manufactured products.

[00:13:23] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s just astonishing to me that we would be using lead for almost anything at this point, given what we know about it.

[00:13:33] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. Yeah. And thankfully, it’s not as much as it used to be, but just any of it is alarming.

[00:13:40] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. So what other chemicals are we worried about in plastics?

[00:13:45] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Alkylphenols are another one, and they’re very similar to phthalates in terms of their function. They’re used to make plastics more moldable, thinner. They’re one of these, you know, so-called plasticizers. But they undergo a wide range of chemical reactions during the commercial application process. And so with that, you get a lot of, you know, chemical products that can be dangerous. In fact, some of them are, you know, certain alkylphenols cannot be used in the EU because of the products that they ultimately make during these chemical reactions.

And so, you know, that’s another one where we know that the ultimate result is, you know, we’re essentially making an endocrine disruptor during the commercial process of using alkylphenols. And so as those change, the alkylphenols become, you know, something else and that ends up being an endocrine disruptor.

[00:14:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. This happens a lot. We think about ingredients, but we don’t think about how things change when we process those ingredients. This happens in food, right? With acrylamides being produced in the cooking process. So they’re not.

[00:14:59] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes.

[00:14:59] >> Molly Jacobson: In the food. The food becomes, it’s saturated with them or coated with them depending on what kind of food you’re making and how you’re cooking it. When those chemicals, it’s that high heat, that delicious char.

[00:15:13] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes.

[00:15:13] >> Molly Jacobson: It’s not good for you.

[00:15:14] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Unfortunately.

[00:15:15] >> Molly Jacobson: Is there any other chemical you wanna talk about?

[00:15:18] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: I think one of the things we often don’t think about is, you know, the chemicals that are released during the making of plastic. So there are some chemicals that are used in plastic or some plastics that, you know, for example, PVC is a well-known one. Polyvinyl chloride. It’s in your plumbing system, you know, it can be on, you know, the siding of your house.

[00:15:40] >> Molly Jacobson: It’s everywhere.

[00:15:40] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: It’s, it is everywhere, right? PVC in and of itself, even though it’s a plastic, is not a known carcinogen. The problem with PVC is that, often, BPA has to be added to it to make it moldable. So there’s that aspect of it.

[00:15:55] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:15:56] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But what’s really, you know, kind of more of an issue, in my view, is that there’s a chemical that is released, vinyl chloride, a gas, that comes out of this during the manufacturing process of PVC. And vinyl chloride is a known carcinogen. And so, I mean, the manufacturing process of making this plastic ends up releasing this known carcinogen that is really, really, you know, a known endocrine disruptor, you know, has a lot of environmental outcomes. We’re seeing it right now, you know, in the news with the train derailment.

[00:16:29] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:16:30] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: That was one of the chemicals that they were worried about in Ohio.

[00:16:33] >> Molly Jacobson: Yes.

[00:16:33] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: You know, and we’re seeing the environmental fallout from something like that. And those are things that I think we also need to be mindful with plastic is, yeah, maybe the end product or that the, the chemical that’s being used is not in and of itself a carcinogen, but it emits something during the manufacturing process that is, and so you’re still being exposed to something that is an endocrine disruptor in the process of that plastic getting from, you know, point A to point B in being made.

[00:17:02] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. There’s consequences to every decision we make, isn’t there?

[00:17:06] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, and it’s exhausting sometimes, right?

[00:17:09] >> Molly Jacobson: It really is. It’s really, I mean, I understand why people don’t pay attention to this stuff because it’s overwhelming when you start to really look at it. ‘Cause I’m imagining a world without PVC and I can’t.

[00:17:22] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. Yeah. It’s one of those things that, because plastics are so ubiquitous and pretty much unavoidable, even if you buy something that’s not plastic, it probably came in plastic packaging. Right?

[00:17:34] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:17:34] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. So there is kind of this element of helplessness and hopelessness in terms of, you know, dealing with these things. So it’s, it’s kind of, you know, an ignorance is bliss moment, not having to think about it and to focus on other things that, you know, are more pressing in your life at that time, but are ultimately affecting you regardless.

[00:17:52] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. So let’s talk a little bit about, briefly, let’s go over the history of plastic that you found, because I thought this was fascinating. I’m really glad you included it in your article. And to me it speaks to the hope that the, the humans have for the future.

[00:18:09] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:18:09] >> Molly Jacobson: We’re always trying to solve problems and sometimes we create problems and we try to solve them. And I guess we just like solving problems ’cause we are always creating more to solve.

[00:18:20] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Exactly. Yeah. It seems like that, you just roll from one to another.

[00:18:25] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah.

[00:18:25] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But you’re right. I mean, plastic over the last two centuries has had this really interesting history. Kind of the ancestors to plastic had been made prior to the mid 1800s. Inventors had experimented with different chemicals and had made a product that was, that was plastic like. But really the drive to come up with something that could be mass produced came from manufacturing industries that used ivory and specifically elephant ivory. You can get ivory from other animals, but typically we focus on elephants. And during that time period, elephants were certainly taking the brunt of that.

And so during that time, you know, manufacturers were like, ivory’s getting way too expensive. We can’t afford it because we’re running out of elephants. We’re decimating these elephants. And so they put out a call to inventors in the mid 1800s and they said, if you can find us something that functions and looks like elephant ivory that we can use for, you know, ivory at that time was used for so many things, jewelry and trinkets and chess pieces and billiard balls for pool tables.

And you know, it wasn’t this infinite resource and there was a species that was suffering because of that. And so this inventor kind of answered that call and, um, he ended up experimenting with hardened nitro cellulose. And with that he had kind of, you know, he called it celluloid and patented it under that name.

And what was so special about his product was that, you know, it could be produced en masse. So it wasn’t something that was just kind of a one and done that previous inventors had done. It was something that, you know, could tangibly be manufactured on a large scale and, you know, fulfilled the needs of these manufacturers that wanted to find an alternative product to, you know, something like elephant ivory.

And even then, celluloid had a bit of a problem because it relied on boiling down the bark of the camphor tree. So that was one of the ingredients that had to go into it. Camphor tree is, you know, it’s a species that we have in the United States, it’s in states like Florida, but you know, even though we had moved away from elephant ivory, we still were relying on Mother Nature for a resource in terms of this camphor tree bark.

And so that made that product ultimately limited by a source that humans couldn’t, you know, really control. Um, but then in 1907, another inventor came along and he was the one that finally designed, you know, the first synthetic plastic that didn’t rely on any kind of natural outside resources. And so that really catapulted the possibilities of what could be done with plastic.

And so that’s kind of, you know, the, the, the actual story of it getting started seems like, okay, well that’s good ’cause we reduced pressure on these, you know, wild populations of animal species, trees. But now, you know, by the 1960s we were finding plastic in the ocean. And so it kind of, you know, took decades to really pique people’s interests, but then, you know, as early as the 1960s, people were kind of calling out the alarm on what plastic was doing to the environment.

[00:21:34] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. So let’s talk about what it does to the environment and why. Plastic basically breaks down over time. All plastics do. Am I right about that? That’s my understanding.

[00:21:45] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. I mean, any chemical can theoretically break down, like chemicals are held together by these bonds. And those bonds can break. And so bonds can break due to all sorts of things. You know, you can think of temperature and, you know, and, and things like that are what make plastic kind of dangerous, right? Because those chemicals have to go somewhere. And now that they’re not in a stable form. And so that’s where you get the leaching of these chemicals out of plastic once those bonds break.

[00:22:14] >> Molly Jacobson: So I’m thinking about, I like to come up with a metaphor because that’s, because I’m not a scientist, I’m a writer. Um, so I’m thinking about like the mortar between bricks.

[00:22:25] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes.

[00:22:25] >> Molly Jacobson: Let’s say that you have a brick wall and there’s mortars. The mortar would be like the chemical bonds, and the bricks are the chemicals. So if that mortar degrades over time, you’ll have those bricks just fall out of the wall. And it happens, right?

[00:22:38] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. Or the chemicals will release from each other. I mean, they’re kind of holding each other together too, so you can think of – yeah, that’s a really good analogy. I mean, the brick kind of being the plastic itself, right? And the plastic is composed of these chemicals, and as these bricks kind of fall out, you know, now they’re in the environment.

[00:22:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:22:56] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And as that brick wall gets fewer and fewer bricks, eventually the whole wall is gonna come down, right? That’s a good analogy. I like that.

[00:23:04] >> Molly Jacobson: And then you’ve got all of these bricks that are, unfortunately, carcinogens and they’re not being held safely together in a solid thing that you can use, but instead, like, so like, so if I pick up something plastic and it’s old, sometimes plastic gets that like, like a little powder on it. Well, almost. Or here in the tropics, ’cause I live in Hawaii, we get like, things break down quite quickly. Like even uh, supply lines that we use for plumbing. I’ve never had to replace a supply line in my life in the Northeast.

But here, every five years we have to replace them because they are breaking down and they’ll spring a leak really easily. So that actually makes me think our water supply is being contaminated over time. I’m not just going to replace them because they spring a leak. I think I’ll replace them because they’re releasing plastic chemicals into my water. Oh my goodness.

[00:24:01] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: I know this stuff is scary.

[00:24:03] >> Molly Jacobson: It is scary. Yeah. So like don’t use plastics, I would imagine, when they seem old. Like it’s not just about, it’s no good anymore, it doesn’t look good anymore, but it might actually be dangerous.

[00:24:18] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, it’s a good idea to replace your plastics for sure. You know, and if you can switch to an alternative.

[00:24:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:24:24] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: If you’re going to bother with replacing your plastics, it’s probably best to just switch to something like glass or, you know, I’ve switched out all my Tupperware containers the last couple of years to, you know, glass ones. And so yeah, older plastic is definitely not going to, you know, it’s going to be leeching things for sure. And if you’re like heating up your food in it or you know, keeping food in general in it, right, like that’s probably, best to replace that all together if you can, but definitely get something new if you have to use plastic.

[00:24:55] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah, so when plastic food containers are, you know, you put your food in ’em, you put ’em in the freezer, or you take ’em out of the freezer, you let ’em thaw, and then you put ’em in the microwave to heat it up, that’s not good because that extreme of temperature is, of course, going to weaken those chemical bonds as well. Right?

[00:25:12] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Exactly.

[00:25:13] >> Molly Jacobson: So best not to keep food in plastic in general.

[00:25:17] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: If you can avoid it. Yeah.

[00:25:18] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh my goodness. So what do these endocrine disruptors do when they’re released into the environment?

[00:25:24] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: They can affect wildlife. There’s a lot of really interesting research right now on the way that these endocrine disruptors are impacting species like fish and changing the sex of fish in certain waterways and really altering the development of species. A lot of these species, you know, that live in these fragile environments are very specifically adapted to those specific environments, and so introducing something new into it or flooding it with something like endocrine disruptors, you know that wildlife, they’re going to absorb those chemicals.

And then, you know, they’re kind of stuck with the consequences of that. And that can lead to some really weird population dynamic outcomes, like being heavily skewed towards one sex or the other. And ultimately, you know, those chemicals those animals are ingesting are gonna have similar outcomes as they would in us over time.

And that’s still something that we’re trying to understand, especially when it comes to something like cancer, you know, what is the direct link between plastics and those chemicals, endocrine disruptors, and the risk and development of cancer. But it wouldn’t be that farfetched, I would think, that we would start to see something like a cancer or a disease spring up because of these endocrine disruptors that are in the environment.

It all just kind of depends on how long and how much, and what the exposure level ultimately is and how sensitive the species is.

[00:26:56] >> Molly Jacobson: What do we know about dogs specifically and cancer risk when it comes to plastics as a carcinogen?

[00:27:05] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: I think – it’s so tricky with cancer because there’s never just one cause.

[00:27:10] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:27:11] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: It’s so multifactorial and things that you’re not even, you know, your dog’s genetics, you can’t change that.

[00:27:18] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:27:19] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And so there are really things that are underlying that are, you know, you’re kind of trying to control what you can. And, and endocrine disruptors can certainly play a role, especially with the endocrine related cancers. So like mammary cancer in dogs, um, we see like kind of an uptick in that. There was a study on tumor growth on a prostate in dogs and exposure to plastic that increased the growth of those tumors on the prostate. And so we know that there’s, you know, a perceivable link between the use of plastics or at least exposure to those endocrine disruptors and possible cancer disease outcomes with dogs. But actually picking that apart is, is really tough to do, to be able to pinpoint, you know, exactly what the underlying causes are. And, and a lot of that too is because we just need more time. You know, these things aren’t necessarily working overnight to cause these big mass changes. And so you could have a study that, you know, would take decades to actually be able to pinpoint these effects. And you know, we know that dogs unfortunately don’t live that long.

[00:28:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:28:24] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But we definitely know that they’re impacting their bodies similar to the way that they impact ours. And dogs are usually pretty good models when looking at diseases and kind of transferring knowledge from humans to dogs and vice versa. And so, you know, if we know it’s affecting us, it’s definitely affecting dogs as well.

[00:28:41] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. That is a problem with cancer. So often we wanna know like, how do I prevent this? What do I do? And the answer too often is, we don’t really know exactly how to untangle all of these factors. We just know that we need to reduce as many factors as we can.

[00:28:59] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:28:59] >> Molly Jacobson: It’s really not simple and it never is.

[00:29:02] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And it’s, that’s, that’s what makes I think cancer so frustrating. Right. And like you said, you never, you wanna do as much as you can to reduce risk. And I think that’s really the goal to keep in mind is you might not be able to eliminate the risk, but you can certainly do things to reduce it.

[00:29:16] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. So let’s talk a little bit about your background and then I wanna talk a little bit about those simple things we could possibly do. But let’s do that after a break. We’ll be right back with Dr. Charlotte Hacker.

And we’re back with Dr. Charlotte Hacker. Let’s talk a little bit about your background as a wildlife expert and what your day job is. I wanna hear a little bit about you.

[00:29:47] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Um, so I, I wear many hats I feel like these days. My research and my work is kind of at, more so at the intersection of wildlife, ecology, biology, and international relations and policy. And so my work most recently has been helping to shape international policies that work towards, and, you know, protecting the environment and protecting species. And so that’s kind of my day job right now.

But I, I came from a very heavily like field biologist based background. I did conservation genetics for my PhD. So that’s essentially, uh, you can kind of think of it as like crime scene investigation with wildlife.

[00:30:30] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, I love it.

[00:30:31] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: We use a lot of the same techniques.

[00:30:33] >> Molly Jacobson: Really?

[00:30:33] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So my job was basically to walk around the mountains and pick up animal poop. And animal poop contains DNA. So you extract the DNA and you can get all sorts of information. You know, you treat it kind of like a piece of evidence at a crime scene. We’re using the same kind of molecular techniques to get that DNA and to figure out, you know, what species deposited the scat. We can get individual profiles to see who’s moving around in the area. We can even look at the DNA of what that particular animal ate to get an idea of diet.

[00:31:04] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow.

[00:31:05] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And I, I did this in very high altitude environments. So there’s some degree of molecular mechanisms that allow species to live in these environments where there’s not as much oxygen.

[00:31:15] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:31:15] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And I became interested in that, trying to understand what does that look like genetically. So I focused on snow leopards for that.

[00:31:22] >> Molly Jacobson: Beautiful animals.

[00:31:23] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. It was, I mean, I say that casually. Um, I had a really, I’ve been very fortunate with the things I’ve gotten to do in my career. And a lot of those same pathways and those genes that are involved in hypoxia adaptation are involved in tumor genesis and cancer.

[00:31:38] >> Molly Jacobson: Ah-huh.

[00:31:39] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And that kind of opened the flood gates for me in terms of my interest in, in just in general, the molecular mechanisms genetically that may lead to cancer or be something that puts a particular species, organism, individual at risk for certain types of cancer. And so that’s kind of where that component of the work that I do for you guys comes in. Um, and then, you know, all of that started with my childhood dog, right? Like she’s the reason I, I love animals and wildlife and everything kind of stems from her.

So tracing it all the way back, you know, it started with my pet German Shepherd and now I’m, now I’m here.

[00:32:15] >> Molly Jacobson: What was her name?

[00:32:17] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Her name was Gladys.

[00:32:19] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, Gladys the German Shepherd.

[00:32:23] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Gladys the German Shepherd. My dad brought her home one day.

[00:32:26] >> Molly Jacobson: Did you name her?

[00:32:27] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: No, my dad did.

[00:32:29] >> Molly Jacobson: What an amazing name.

[00:32:31] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, he, I came off the bus one day and he had a puppy.

[00:32:34] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh.

[00:32:34] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And that was probably one of my like first core memories as a kid.

[00:32:39] >> Molly Jacobson: Sure.

[00:32:39] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: I was I think in kindergarten, first grade, maybe.

[00:32:43] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh my God.

[00:32:43] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So, yeah. Oh, Gladys.

[00:32:46] >> Molly Jacobson: That must have been a really, really good day in your life.

[00:32:49] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Oh my gosh. Like definitely top. I still, you know, when people ask me, I think that still comes to mind. I’ve had many good days, been very lucky, but that one definitely comes to mind.

[00:32:58] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s so sweet, Charlotte. That’s one of the things that I love about the work we’re doing is that everybody involved has a dog, you know, a dog’s love in their heart that inspires their work. And it’s so satisfying to share that with so many people. That’s so great.

[00:33:16] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:33:16] >> Molly Jacobson: So if your dad were giving you Gladys today, what kind of toys would you get her and what kinds of, like, what would you get for your dog today, knowing what you know now about plastics?

[00:33:28] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. Well, I, I do have a Miniature Dachshund now.

[00:33:31] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s right. Of course you do.

[00:33:32] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But she’s, she’s not much of a toy, she kind of, she’s more of like a bone kind of chewer.

[00:33:38] >> Molly Jacobson: Uh huh.

[00:33:38] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But I, I would avoid plastics as much as possible. I would focus on things like rope toys, more natural substrates, and, and things like that. Especially if, you know, Gladys was a chewer, she would chew toys up, and you’re breaking those bonds.

[00:33:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Literally.

[00:33:57] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: As the dog, you know, your dog is chewing and they’re breaking the bonds and you know, swallowing pieces by accident, whatever it is. And it’s really unfortunate because the dog toy industry is not nearly as highly regulated as something like the kids’ toy industry. And you know, with dog toys, really the only rule is that you can’t intentionally add harmful substances. And that list of harmful substances is, you know, much shorter than what we would see in children’s items.

And so, even though, you know, you could have a kid with a bouncy ball and have a ball that looks almost identical that you bought at a pet store for your dog, and I can almost guarantee that the chemicals in your dog’s toy are gonna be different than what’s in the kid’s toy, and they’re gonna be the ones that are not, you know, that, that are known to be more dangerous. And it’s cheaper to manufacture, there’s less oversight, there’s all sorts of reasons as to why they’re used.

[00:34:55] >> Molly Jacobson: Uh huh.

[00:34:56] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But I think even avoiding, you know, you, you can try to swap out for kids’ toys, sometimes those overlap enough, so if you are looking to get your dog something plastic, squeaky, whatever, you know, it might be worth looking into something that’s meant for a kid because it’s less likely to have some of those dangerous chemicals. And so I, I would avoid those altogether, you know, with the understanding that some dogs, that that brings them joy and what’s the trade off.

[00:35:22] >> Molly Jacobson: Uh huh.

[00:35:23] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: You know? So, but just try to be, be mindful. And some pet companies are ahead of the curve. And they are already, you know, not using those chemicals and you can certainly seek those companies out. They’re gonna be more expensive toys, but in the long run, way better for your dog. So there are, you know, dog focused toy companies that are doing above and beyond what they’re, you know, required to do on a regulatory level.

[00:35:49] >> Molly Jacobson: And they’re probably talking about that in their marketing, they’re probably saying we manufactured at kids’ regulations and/or, you know, they’re talking about all of these chemicals of concern and saying they don’t have them in their products, or they’re using exclusively like hemp or wool to make their toys so that you know for sure that that is not a plastic.

[00:36:12] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:36:13] >> Molly Jacobson: So I imagine plastic bowls, plastic, yeah, like you would wanna use a glass or stainless steel.

[00:36:20] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. Anything that your dog, you know, with their, that their food or water touches should not be plastic if you can help it. There are, like you said, tons of alternatives. Glass, stainless steel, ceramic. You know, depending on how old it is, there are some dangerous chemicals in older ceramic glazes.

[00:36:37] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:36:37] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So to be mindful of that, but different, you know, topic.

[00:36:41] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:36:42] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But yeah, you could definitely switch out. Or even, you know, I think of the big plastic containers that some people keep their dog food in.

[00:36:49] >> Molly Jacobson: Uh huh.

[00:36:49] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So instead of having it in the bag, they’ll put it in big plastic containers. If you can switch that out for like metal or something like that, that’s, you know, a really kind of easy thing to do. Don’t keep it in the bag necessarily, ’cause the bag is probably lined with plastic.

[00:37:05] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, that’s true.

[00:37:06] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: So yeah, it’s always something, right?

[00:37:11] >> Molly Jacobson: Decant your dog food.

[00:37:13] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Decant your dog food.

[00:37:18] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, is there any other thing we can do on a practical level to reduce our dog’s exposure to plastics?

[00:37:27] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: If they’re not chewing it, it’s probably not too terrible for them. If you have a dog that’s like, you know, if you have them in a crate, for example, if you crate train your dog and they have the little plastic floors in the bottom, if your dog is a chewer and chews that, you need to find an alternative or you should try to find an alternative.

[00:37:43] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:37:43] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: But if your dog is just laying in it and it’s got its blanket and it’s just chilling, it’s just hanging out, you’re probably okay. Your dog’s probably not getting that kind of more troublesome exposure in terms of the risk of ingesting those chemicals in the plastic.

[00:37:58] >> Molly Jacobson: That makes a lot of sense. So I’m kind of back where we started, which is we should be concerned, but try not to panic because we can’t live in, in a plastic free bubble in the modern day.

[00:38:10] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, you’re absolutely right.

[00:38:13] >> Molly Jacobson: Is there anything else that listeners can do on a practical level, other than reducing their own exposure, their dog’s exposure? Are there any other action that if somebody who, you know, like should they write their senator, should they call Congress? Like, is there, is there any important legislation going on or anything that they should specifically ask for?

[00:38:36] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: I mean, it seems like things are constantly changing or being, you know, in the process of being updated and, and you can, you can literally vote and you can vote with your wallet, right. You can choose to buy certain products. You can send a message that way.

[00:38:50] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. We are in a capitalist society.

[00:38:53] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah. And where you put your money, they will eventually listen. That can be intimidating. I hear people say often, you know, well, I’m just one person and you know, how is my one choice going to, you know, make a difference? And it’s like, okay, well how many people are listening to this podcast and now going to check labels for BPA, right?

It infiltrates. It does eventually kind of get out there and can make a difference, and so, try to, you know, keep that in mind when you feel like you’re just one little consumer. You know, you’re part of a, a massive, very, very effective, you know, group of people that can kind of incite these movements for change.

And I think what’s, what seems to me the most difficult in terms of crafting new legislation and what holds it up a lot is this disparity on how much is too much, what are the actual toxic levels. So for example, you know, the amount of BPA that can be in something, or the amount of BPA that a human can be exposed to within a lifetime that is considered safe, is way higher than what it is in the EU.

[00:39:57] >> Molly Jacobson: Ah.

[00:39:57] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And the EU just recently reduced that level and dropped it, you know, by thousands of percent. So even if you have legislation that’s going through and being pushed through, that’s great, it’s usually for the better, not always, but that kind of depends on politics and all sorts of other things, and where the money is going and coming from. But you still wanna keep in mind that just because it’s regulated to a certain level doesn’t mean that we really have a good handle on that level being safe. And that’s part of the scientific process.

We’re constantly adding in new information and updating things and you know, sometimes we’re wrong. But even new legislation is, take it with a grain of salt sometimes in terms of what is being put out there.

[00:40:46] >> Molly Jacobson: Before we started recording, we had a a little conversation where we were talking about healthcare and how in a country where healthcare is paid for by the taxpayers via the government, where there’s a universal healthcare, for lack of a better word, that government is incentivized differently than it is in a system like ours. In a system like ours, the government is not incentivized to prevent sickness as much because it doesn’t have to pay for the treatments.

[00:41:19] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:41:20] >> Molly Jacobson: So it’s possible, in my layperson’s mind, I’m not a politician, I’m not a scientist, but it’s possible that we are looking at lower levels in the EU and countries like Japan because those are countries where they take care of the healthcare costs associated with having citizens. And they are directly responsible.

[00:41:45] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:41:45] >> Molly Jacobson: For the health of their citizens. And so they do more to prevent illness there than we do here in the States. And I just think that might be something for everybody to, to think about a little bit, that maybe if we, whatever your thinking is about universal healthcare, perhaps we should be thinking about it as a way to incentivize all of these policies a little bit differently because a lot of things fall out from that. When you’re looking at cutting costs in healthcare because you have to pay for it, prevention becomes much more important.

[00:42:21] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes. Yeah, that’s a really, a really good point.

[00:42:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. So maybe indirectly that’s something people could do, is keep pushing for that.

[00:42:29] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Exactly. Yeah. And push, you know, like I said earlier, you might feel like you’re not moving the needle at all, but you as an individual have, you know, a lot more power and a lot more influence I think than we give ourselves credit for.

[00:42:41] >> Molly Jacobson: I think so.

[00:42:42] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: And we’ve seen changes happen in the past, so it’s possible.

[00:42:45] >> Molly Jacobson: Yep. It is. And lobbying from the public does matter to politicians. It doesn’t matter in all cases, but it does matter if they pay attention when they get phone calls.

[00:42:56] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah.

[00:42:57] >> Molly Jacobson: Well, I just so appreciate you coming on the show and doing all of this work and writing the great article and being your sciencey self. And thank you so much, Charlotte, for joining us today.

[00:43:12] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yeah, no, thanks for having me. This was fun. It was good to, good to chat.

[00:43:16] >> Molly Jacobson: So good to chat and I’m sure that we will have more to talk about later.

[00:43:20] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Yes.

[00:43:21] >> Molly Jacobson: But thanks. Thanks for joining us today.

[00:43:23] >> Dr. Charlotte Hacker PhD: Of course.

[00:43:24] >> Molly Jacobson: And thank you listener. There’s a lot we don’t know or understand about how plastic can impact the body, but the more we learn, the more we understand, and endocrine disruptors and other compounds present in plastic or produced during the manufacturing process can absolutely be harmful. Repeated exposure to these chemicals over time may play a role in the development of diseases such as cancer, both in humans and in dogs.

So check out the show notes for Charlotte’s list of ways to reduce plastic exposure and please read her article. You can find that on dogcancer.com under Cancer Causes and Prevention.

I’m Molly Jacobson, and from all of us here at Dog Podcast Network I’d like to wish you and your dog a very warm, Aloha.

[00:44:13] >> Announcer: Thank you for listening to Dog Cancer Answers. If you’d like to connect, please visit our website at dogcancer.com or call our Listener Line at (808) 868-3200. And here’s a friendly reminder that you probably already know: this podcast is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It’s not meant to take the place of the advice you receive from your dog’s veterinarian.

Only veterinarians who examine your dog can give you veterinary advice or diagnose your dog’s medical condition. Your reliance on the information you hear on this podcast is solely at your own risk. If your dog has a specific health problem, contact your veterinarian. Also, please keep in mind that veterinary information can change rapidly, therefore, some information may be out of date.

Dog Cancer Answers is a presentation of Maui Media in association with Dog Podcast Network.

Hosted By

SUBSCRIBE ON YOUR FAVORITE PLATFORM

Topics

Editor's Picks

CATEGORY