EPISODE 178 | RELEASED August 1, 2022

All About Radiation for Dogs | Jenny Fisher

What kills brain cancer cells, takes only 5-7 minutes, and provides pain relief from osteosarcoma? Radiation therapy.

SHOW NOTES

Radiation therapy can sound very scary to many dog lovers. But it can be extremely useful for dog cancer, both to destroy tumors and to provide pain relief.

Jenny Fisher is a veterinary technician specialist in oncology, and has helped many dogs through radiation treatments. She explains all things radiation therapy, from the different treatment types to its best uses and potential side effects.

If you’ve ever wondered about the difference between teletherapy and brachytherapy, why some courses of radiation are short and others long, or what a dog experiences when dropped off for a treatment, this episode is for you.

[00:00:00] >> Jenny Fisher: The one that’s absolutely amazing is with lymphoma. Lymphocytes, they melt, melt like butter when they are in the face of chemotherapy and radiation. And you may have this patient that has these really large lymph nodes that’s impacting their ability to breathe and they can be treated with radiation and literally be normal within 24 hours.

[00:00:22] >> Announcer: Welcome to Dog Cancer Answers where we help you help your dog with cancer.

[00:00:28] >> Molly Jacobson: Hello friend, we talk about chemotherapy and diet and alternative therapies a lot here on Dog Cancer Answers, but there’s another really important treatment to consider. Radiation can be used to treat a local tumor and hopefully cure it, but it can also be used for pain relief.

And so to discuss that today, we have Jenny Fisher. Jenny Fisher is a registered veterinary technician, and she’s also a veterinary tech specialist in oncology with years and years and years in the radiation vault helping dogs receive radiation treatments. So we’re going to ask her, all the things.

Jenny Fisher, welcome back to Dog Cancer Answers. We are so thrilled to have you join us again today to talk about radiation.

[00:01:16] >> Jenny Fisher: Hi, how are you? It is an honor to be back.

[00:01:19] >> Molly Jacobson: Thank you very much. I wanted to get your insight as a oh, what is your oncology…?

[00:01:26] >> Jenny Fisher: VTS.

So Veterinary Technician Specialist in the area of Oncology, and we go through a specific rigorous program for that to be able to call ourselves that.

[00:01:37] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. And so you specifically are here today to tell us about what happens during radiation treatments for dog cancer. And I understand there’s a couple of different kinds of radiation that you’ve assisted in and that you can help explain to us.

[00:01:55] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely. So when I talk about radiation, I, I like to split it into two categories.

So there’s diagnostic radiation, things like x-rays where we’re trying to diagnose a problem. And then there is therapeutic radiation. So a radiation treatment used to treat a diagnosis.

[00:02:17] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:02:17] >> Jenny Fisher: Now, when we’re talking about therapeutic radiation, there are two different types of that type of therapy, right?

So with therapeutic radiation in veterinary therapy, we have what’s called teletherapy, which is pointing a beam, like an x-ray machine, a big machine at the patient, and delivering the radiation that way. We also have what’s called brachytherapy, which is where the patient is implanted or injected with a radioactive material that is going to be used to treat the condition.

So one of the big misconceptions with the radiation that comes out of the machine, the teletherapy, people think that their pet’s gonna be radioactive after that treatment, and that’s not the case. Those pets do not come home radioactive. They’re not glowing. They don’t have to be isolated. But if it is a pet that receives brachytherapy where they have the actual radioactive source administered or applied, that can be a different scenario.

So in situations like I-131 for hyperthyroidism in kitty cats, those cats have to be isolated for a period of time until they clear that radioactive isotope. So, very important to know when you’re talking to your veterinarian about radiation, and typically you’ve had a diagnosis of cancer and been referred to the oncologist, you’re going to wanna ask things, how is the radiation delivered? Where will it be delivered, and will my pet need to be isolated for a period of time? All right.

[00:03:58] >> Molly Jacobson: And the isolation is to protect everybody else.

[00:04:03] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. It’s to protect the pet family and the pet parents, you know. Human medicine, you may go to the hospital and get a radioactive isotope and the release orders are much lower actually than we may have in the veterinary space. So you may not have to be isolated for as long when you have your I-131 and your kitty cat may have to stay, you know, a little bit longer than you.

[00:04:26] >> Molly Jacobson: And they’re staying in the hospital.

[00:04:28] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. They are, and it’s in an approved radiation safety facility. So an approved area where they are housed.

[00:04:36] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:04:37] >> Jenny Fisher: It’s separate from the rest of the population.

[00:04:39] >> Molly Jacobson: How often is brachytherapy – did I say that right? Brachytherapy.

[00:04:42] >> Jenny Fisher: Brachytherapy.

[00:04:43] >> Molly Jacobson: Brachytherapy. How often is brachytherapy used in cancer in dogs?

[00:04:50] >> Jenny Fisher: So not as commonly anymore, but we use it a lot in horses. So with our horses, they’re too big to give chemotherapy. One, the amount that would be required would be so incredibly expensive, and the hazard of administering chemotherapy in a large horse that then is gonna go in a stall and, and urinate. And so the safety hazards make chemotherapy almost impossible in our horses.

So using something like implantable or injectable radiation works wonderfully in a lot of those cases. And we also use some of those radioactive isotopes to perform bone scans on athletic horses as well, to look for injuries.

[00:05:31] >> Molly Jacobson: Interesting. Okay. So-

[00:05:33] >> Jenny Fisher: It is.

[00:05:34] >> Molly Jacobson: Brachytherapy for dogs with cancer is going to be a more uncommon scenario than using the machine, the teletherapy.

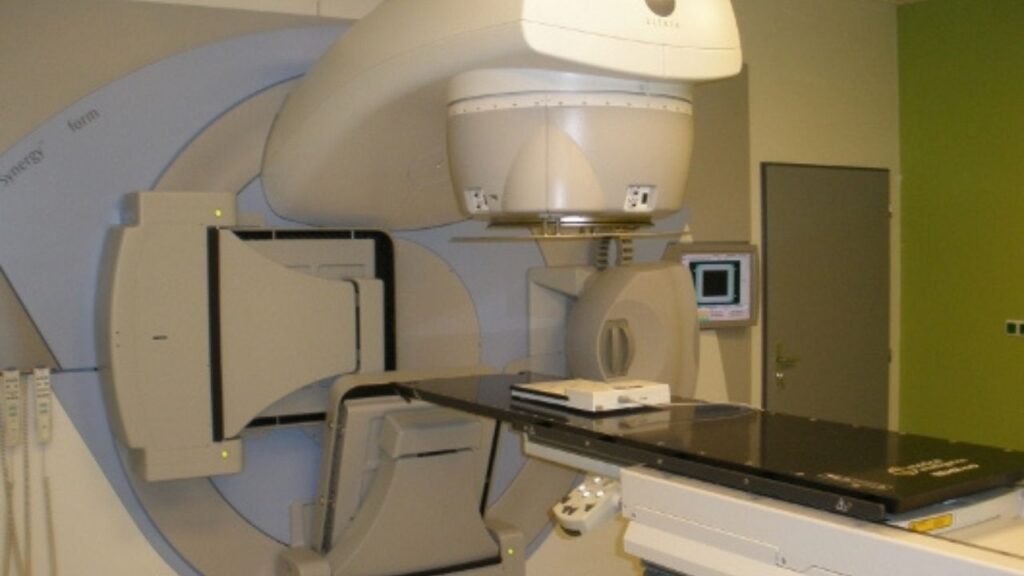

[00:05:43] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. And the most important thing with our teletherapy is the type of machine that’s being used. There are multiple different types of machines based upon their energy and, as well as what type of energy that is. Is that electron energy? Is that photon energy? So the ability of the machine itself can dictate what type of radiation protocol is going to be recommended.

[00:06:12] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

I mean, most of these radiation services are offered at big teaching hospitals anyway, because those are very expensive machines, right? The typical practice doesn’t have one.

[00:06:22] >> Jenny Fisher: That’s correct.

They are multimillion dollar machines. The software to run them is about a half a million dollars.

[00:06:29] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, my goodness.

[00:06:30] >> Jenny Fisher: You also have to have a full-time physicist on staff by law to maintain the machine. You know, there’s so many costs. You have to have a proper housing structure to locate that machine in and we call that the radiation vault. So if you ever hear people refer to it as the vault, that’s, that’s what they’re speaking of, because it is a vault. Um, it is usually two to three feet of lead or concrete.

[00:06:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Whoa.

[00:06:54] >> Jenny Fisher: Yes.

[00:06:55] >> Molly Jacobson: And is that just one treatment room that’s surrounded by that? Or is that like an entire building that has those thick walls?

[00:07:01] >> Jenny Fisher: It’s one treatment room. So it sits kind of in the middle. There’s one way in one way out. Those doors are closed during treatment, which brings up another point about veterinary technicians in the radiation vault.

Our pets, when they’re getting that, that radiation therapy, they have to be completely still. Because the positioning is so precise, anytime – you know, think about a Greyhound with a really deep chest. If you have a mass on the chest and they take a really deep breath, right, that little bitty, tiny mass, if it only had a one centimeter margin or field around it, when they breathe, it comes out of your field. So.

[00:07:42] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh.

[00:07:42] >> Jenny Fisher: We have to use general anesthesia to keep those pets very, very, still.

[00:07:47] >> Molly Jacobson: Every time. For every treatment.

[00:07:49] >> Jenny Fisher: Every single treatment. So there are multiple patients that I’ve anesthetized 40 and 50 times because they’ve had multiple rounds of anesthesia. And I’ll tell you, I am more comfortable on the 50th than I am the first, because I know that patient so well, if that patient sneezes incorrectly, if there is one abnormality on the ECG, I pick it up instantly, um, because I’ve learned that patient over a period of time.

But yeah, that, that general anesthesia, which is usually run by a veterinary technician, so they’re completely anesthetized. Sometimes with specific tumors, depending on where they are in the body, we have to use positioning aids to get a patient in a specific position.

So if they have an oral tumor where we need to have their mouth opened so we’re not getting the upper jaw in the field of view or the field of treatment and we just wanna treat that bottom jaw. We want to spare as much normal tissue around that tumor as possible. So positioning devices like bite blocks or big pillow pads called Vac-Loks, where we put them in and then we suck all the air out and it conforms to their body.

So the next time we anesthetize them, we simply put them back in their mold, we have them lined up with specific marks, they fit specifically back into that mold, measuring up where they were. And then we actually, uh, will take images with that machine and look at bony anatomy with a, uh, screen that we put into the machine that shows us distance.

So if we need to move one centimeter to the left or two centimeters to the right or three millimeters cranial, that’s how we do that. And those patients are anesthetized the entire time. The majority of radiation treatments are only about five to seven minutes. So they’re very short.

[00:09:38] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:09:38] >> Jenny Fisher: Very, very quick. Not like going into surgery. So a lot of times we don’t use very long acting drugs or things like opioids. Uh, we want those patients anesthetized easily and we want them to recover as quickly as possible and as safely as possible, and we want them to go home because they’re gonna be back the next day.

[00:09:55] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So typically the treatment itself, the actual radiation exposure is five to seven minutes, but it sounds like there’s a tremendous amount of prep work. It’s like the thing you’re doing is actually very quick, but the prep for it is longer. How long is the dog in that vault, anesthetized, for a five to seven minute treatment?

[00:10:14] >> Jenny Fisher: Great question. So for the, what we call radiation treatments, we call them fractions. So for each fraction, once the patient is positioned correctly, has been marked for that location, and the plan has already been made, those are gonna be five to seven minutes. That is the majority of the treatments. Almost all of them. On our first time that we treat that pet, that is gonna be a much longer anesthesia, just because we’re doing a lot of that positioning. We’re marking, we’re setting them up.

We may set them up in a position that we get them and they may try to formulate a, a radiation plan from the software and the software may not like our position.

[00:10:52] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh.

[00:10:52] >> Jenny Fisher: And so we have to start over.

[00:10:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:10:54] >> Jenny Fisher: And adjust. There may be vital tissue that’s in our field that we need to reextend the leg. So, that first treatment is typically gonna be somewhere, you know, depending on the team, anywhere from about 30 minutes to an hour.

[00:11:08] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:11:08] >> Jenny Fisher: And that’s typically the longest time that they’re anesthetized throughout their radiation treatments.

[00:11:13] >> Molly Jacobson: And how many – I’m sure it depends on the diagnosis you’re working with, the type of cancer, but how – and all of those factors, every cancer case is so different – but on average, how many times do dogs get radiation treatments?

[00:11:26] >> Jenny Fisher: So we have two courses of therapy. One is our curative intent, not meaning that we will, but that’s our intent. Those patients receive smaller doses of radiation and a larger number of treatments, with a specific type of machine. With that machine, we also have our palliative intent, meaning we’re palliating pain, we’re not intending to cure that local disease. And those patients are given larger doses of radiation, or larger dose per fraction, with fewer treatments.

So typically anywhere from three to 21 on the curative intent, and on the palliative intent, anywhere from two to eight. And the dose is going to be what’s going to be very different between those two.

[00:12:10] >> Molly Jacobson: Why more for palliative versus curative treatment?

[00:12:16] >> Jenny Fisher: That’s an excellent question. With our palliative cases, it is documented that higher dose per fraction of radiation has a higher propensity to cause a radiation induced tumor later. So if we have a really young pet that has an osteosarcoma or something that we’re treating with radiation, we will monitor that pet very closely as they grow and as they age, because unfortunately we know that radiation can induce tumors as well.

We know for a fact, because of human data, that larger doses per fraction increase that propensity to develop a secondary tumor. Our smaller dose per fraction has a much less likelihood to induce a secondary tumor. So those patients that we expect to cure that local disease, we expect them to live a lot longer, right? If we’re in a palliative situation where we know there’s multiple concurrent metastatic disease, or we know that a complete local cure is not possible with that pet, then we want to make them more comfortable.

So we give larger doses to palliate them, to make them more physically comfortable, knowing that we are not going to likely get to that point of having to face those side effects.

[00:13:35] >> Molly Jacobson: I love it. So when you’re pretty confident that you can cure, and this will kill that tumor, then you give the lower doses to make sure that long term risk of a potential other tumor because of the radiation treatment is much lower.

[00:13:49] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

[00:13:50] >> Molly Jacobson: Now does radiation, does it treat, but also relieve pain? That’s in my head, but I don’t know if it’s true.

[00:13:56] >> Jenny Fisher: It does. It’s a fantastic, uh, pain relief modality, and it’s because of all those cytokines associated with inflammation. It actually works wonders. In my personal experience, it is the only modality, including oral drugs, that I’ve seen maintain an osteosarcoma’s patient pain level without having an amputation. It has truly been the one thing in my – if my personal pet were to have, uh, osteosarcoma and was not a candidate for amputation, radiation therapy would be my pain treatment of choice.

[00:14:29] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay, well, that is very helpful, and I’m sure there are many people listening, cuz I know that’s a real concern if people can’t amputate and they’re really worried about their dog being in a lot of pain as a result.

[00:14:40] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

[00:14:41] >> Molly Jacobson: So that radiation treatment really can help to reduce that pain. Is it because it removes the tumor or is it because of the anti-inflammatory effect?

[00:14:52] >> Jenny Fisher: So it’s kind of a two-prong approach, which is why radiation is so fantastic. So it can have a direct effect on the tumor itself, which can be causing pain and painful just because of the effects on the bone. So it can reduce the actual process of the cancer effects as well as reduce the inflammation associated with cancer.

So you kind of get kind of a two prong approach, direct effect to the tumor, to calm the tumor down specifically, and then as well as the inflammatory properties associated. I’ve seen it do fantastic, fantastic things.

[00:15:27] >> Molly Jacobson: Wonderful.

Do you ever assist in CyberKnife or any of the other stereotactic radiosurgery techniques?

[00:15:34] >> Jenny Fisher: I am so glad you brought that up too. So when I was talking about the courses where we talked about palliative and curative intent, and I said a specific machine, I was not referring to a, a, uh, stereotactic type machine. All that really is, in a layperson’s term, is a extremely targeted dose of therapy.

So the, uh, margin is almost non-existent, uh, because they have the capability to really focus and make that actual treatment space, they can give a much higher dose to that area because they are not treating that normal or vital tissue. And that is why the machine type, when I said at the beginning, is so important, that machine type is going to dictate what type of therapies are going to be offered. But certainly, you know, stereotactic is, it’s amazing.

And I have worked with it and it’s kind of like a dream from an oncology radiation technician’s perspective. It’s like working with the Lamborghinis and the Maseratis. And it’s, it’s, it’s amazing. It’s amazing.

[00:16:37] >> Molly Jacobson: Somebody, I think it was Dr. Sue, compared it, she said it’s like, it’s like having a, a laser scalpel that just goes in there and it just so precisely takes it out.

[00:16:47] >> Jenny Fisher: That’s a perfect analogy. Because it is so specifically targeted, they can do those much higher doses, and it’s, it’s fantastic. It’s a fantastic modality if you have access to it.

[00:16:58] >> Molly Jacobson: Right, because there are not a lot of centers that have those machines, the stereotactic.

[00:17:02] >> Jenny Fisher: Yeah. There are not – they’re still gradually becoming more and more, but not even all of the veterinary teaching hospitals have them yet.

[00:17:09] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. They’re very expensive.

[00:17:11] >> Jenny Fisher: They are. That’s the unfortunate part of cancer treatment. It’s why I urge everyone to get pet insurance because it truly does help when we talk about the cancer treatments, it is so expensive. But because of the housing, the machine, the software, the physicists, the technical staff, you know, it is certainly worth its value, but it is certainly not something that’s, unfortunately, available to everybody.

[00:17:32] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah.

I know that all of these treatments do cost quite a bit. What is on average the treatment cost for a course of say, curative radiation.

[00:17:42] >> Jenny Fisher: For a course of curative radiation in the stereotactic setting, you’re probably looking anywhere from $6,000 to $10,000.

[00:17:51] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow.

[00:17:51] >> Jenny Fisher: With a traditional machine, a linear accelerator with like a multi lead collimator where they can do that palliative or different intent, probably anywhere in the $4,000 to $8,000 range.

[00:18:03] >> Molly Jacobson: And is that for the entire course, or?

[00:18:05] >> Jenny Fisher: That is.

[00:18:06] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:18:06] >> Jenny Fisher: That’s for the entire course of therapy.

[00:18:08] >> Molly Jacobson: All right.

[00:18:08] >> Jenny Fisher: Yeah.

[00:18:09] >> Molly Jacobson: This might be a good place to take a break. We’ll be right back and talk some more about radiation in dog cancer.

We’re back with Jenny Fisher talking about radiation. One of the things I know people really have a lot of, um, they don’t really understand how radiation actually works in the body. Is it killing the tumor right away? Is it something that happens over time? What is actually going on when that radiation beam hits the cancer tumor, and unfortunately, sometimes the surrounding normal tissues? What’s going on?

[00:18:47] >> Jenny Fisher: So there are a couple of different ways that we see what that effect is, but to break it down into easy lay person kind of understanding, the way that chemotherapy and radiation both treat cancer, is affect that cell’s inability to divide or replicate or grow.

Now it can do that in a couple of different ways. The big one that we talk about is apoptosis, where we literally cut the blood supply off to that cell. We can also see historically that some tumors, depending on how rapidly those cells divide, we can see a better response rate or a quicker response rate with a rapidly dividing tumors.

Now what are rapidly dividing tumors? There are basically four, but we’re gonna talk about three groupings of cell base, um, when we talk about cancer. So there’s our round cell tumors, which is like lymphoma, mast cell tumor, TVT, histiocytoma. We also have our epithelial tumors, which are our lining cells. That’s going to be 99% of the time a carcinoma.

So if you hear mammary carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, that is a malignant tumor of epithelial origin. We also have our third grouping is our mesenchymal cells. That’s our connective tissue. So cartilage, bone, fat, all of those connective type tissues. They all look differently under the microscope, so how we can get a diagnosis, and they all behave differently.

Our round cells and epithelial cells tend to exfol- or tend to replicate or divide very quickly. So our mesenchymal cells tend to divide very slowly, okay. So when we see something that is round cell or epithelial cell in origin, when we give radiation or chemo, it attacks that cell’s ability in their DNA to go through cellular division.

If they do that at a rapid rate, we can see a rapid response because that inability is, is halted. With those slowly growing tumors or those tumors that, uh, divide very slowly, their cells divide very slowly, we might not see a direct effect on that tumor until months down the road, because those cells are sitting, waiting to divide, but that DNA has already been affected.

So when they try to divide in a month or six weeks, they can’t and they die. So we might not see as rapid of a response with some of those mesenchymal tumors, which are typically our sarcomas, we’re not going to see a lot of times as rapid a response, as far as reduction of tumor size.

But that’s also why we can use radiation therapy, like the case I told you about Bear. Bear’s tumor was a mast cell tumor. It is a round cell tumor. We know those divide very quickly and very fast. So when we give an emergency dose of chemotherapy or radiation, we expect to see a rapid response. If that would have been some type of sarcoma up in his nasal cavity and not a fastly responding tumor, we would not have been able to correct the problem quick enough to prevent damage from permanently occurring within the brain. Does that make sense?

[00:22:16] >> Molly Jacobson: I think it does. And Bear was a dog that you spoke about the last time you were here in that wonderful episode on vet techs. And so I encourage our listeners to make sure they listen to it if they don’t, but he was getting seizures, it turned out the cause was a mast cell tumor in his nasal passages that was impacting his brain.

[00:22:34] >> Jenny Fisher: That is correct.

[00:22:35] >> Molly Jacobson: And that emergency radiation – so does it reduce the tumor? Does the tumor get smaller because the cells have died?

[00:22:41] >> Jenny Fisher: We can certainly see a primary tumor reduction in mast cell tumor. The one we see it that’s absolutely amazing is with lymphoma. Lymphocytes, they melt, melt like butter, um, when they are in the face of, most of the time, the majority of the time, in the face of chemotherapy and radiation. And it’s also why they could be so rewarding to treat. You may have this patient that has these really large lymph nodes that’s impacting their ability to breathe.

So the pet parent is obviously very concerned and you know, you have to breathe. Breathing is important. And they can be treated with those doses of chemotherapy or radiation, and literally be normal within 24 hours.

[00:23:21] >> Molly Jacobson: And it’s just because those cells are so rapidly dividing that they’re just going, going, going, going, going. And so when you stop them from going, they just melt away and there’s no more cancer being generated because they’re all dead.

[00:23:35] >> Jenny Fisher: That’s correct.

[00:23:36] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:23:36] >> Jenny Fisher: And that’s that rapidly dividing, for some of those who may have had chemotherapy themselves, we talk about the effects of chemotherapy in human medicine, about 80% of people receiving IV chemotherapy will have some type of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea. And I like to point out that in the veterinary world, because of the doses that we are using are so much lower, we see less than 10% of our patients actually have severe effects of their chemotherapy.

And the reason we see that in the human space is we talk about rapidly dividing cells, our GI tract is lined with what’s called crypt cells, and those crypt cells are extremely rapidly dividing. So the chemotherapy, like we say, affects the cancer cells, it’ll also affects the normal GI cells that are rapidly dividing, which then destroys the GI flora, which then can cause that, that vomiting and diarrhea.

[00:24:26] >> Molly Jacobson: That vomiting, yeah. So in radiation, when you’re radiating and you have that machine that’s not so precise, the lin-ac machine.

[00:24:34] >> Jenny Fisher: Mm-hmm.

[00:24:34] >> Molly Jacobson: And it’s affecting some normal tissue around the tumor. Those normal tissues that are rapidly dividing, would they also be affected by this?

[00:24:43] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

[00:24:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:24:44] >> Jenny Fisher: And that’s why that positioning is so important. Why we have to pick a position not only that gets all of the normal tissue as, as out, as best as possible, but also to make sure that the potential side effects, if they are going to happen down the road, are as minimal as possible. You know, in my 17 years of treating cancer cases, I think I’ve seen radiation induced tumors maybe five times.

[00:25:08] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:25:09] >> Jenny Fisher: In 17 years. So not extremely common, but they certainly can happen. And when they do happen, unfortunately there’s very little we can do to even give them pain control. They’re very painful.

[00:25:20] >> Molly Jacobson: They’re very painful. So those are the tumors that possibly could arise, very rarely, but possibly could arise in the normal tissues. They were normal when the dog was treated, and then later those tissues have that radiation induced tumor.

[00:25:33] >> Jenny Fisher: That is correct.

[00:25:33] >> Molly Jacobson: Many years later.

[00:25:34] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely. Which is why it’s so important to know about the dosing scheme and the type of machine.

[00:25:39] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So in some cases, the actual tumor is reduced. In other cases, it’s just arrested, stops growing?

[00:25:47] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. So we have the ability to either, uh, in hopes to shrink the tumor, and it’s gonna be much more likely with a rapidly dividing tumor. Or even just to stabilize it, to prevent it from growing more, whether that’s to cause more pain, you know, or impair more function. So both of those. Potential metastasis is what we do with our chemotherapy, but the radiation therapy is specifically for that local area.

[00:26:11] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. Radiation doesn’t take care of metastasis. It really just treats that one tumor.

[00:26:17] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct.

[00:26:17] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. So let’s say that I have a dog and I’ve decided to do a course of curative intent radiation treatment, what do I need to do to get ready for those treatments? What should I expect? What’s the schedule like? What are things that I have to do at home to take care of my dog?

[00:26:35] >> Jenny Fisher: The best thing that I could recommend that you do is to reach out to the facility and talk to the technicians that run the radiation program. Obviously those can vary between facilities quite a bit, but as far as at home, just enjoy your time. Those pets are gonna have to be fasted because of the general anesthesia.

[00:26:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:26:55] >> Jenny Fisher: And you know, truly our goal is to make it as seamless as possible. Make sure to communicate with your veterinary healthcare team if the patient comes home and they’re still groggy all day, they’re not eating, they’re not drinking normally. Because we know chronic anesthesia can also have its problems, we just need the pet parents to be hypervigilant in noticing any changes in those things because communicating that to the healthcare team, they may adjust the anesthetic protocol.

They may use a different drug that maybe might not be as long acting, or administered in a different way. Maybe use a drug that’s reversible so they can send that patient home a little bit more awake. So very important that pet parents play a huge role in management of their pets during the radiation treatments.

[00:27:43] >> Molly Jacobson: So you’re saying during radiation treatments, any side effects you might see like grogginess or lethargy or not wanting to eat would be actually from the anesthesia, not from the radiation.

[00:27:53] >> Jenny Fisher: 100%.

[00:27:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Ah, so that’s something you can control. You can try something else.

[00:27:57] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely. 9.8 times out of 10, it is not the radiation specifically causing the issue. It’s the anesthesia or the position that the patient is in. If they’re an older Labrador that has hip dysplasia and maybe for their treatment they have their hips in an uncomfortable position, and mom calls and goes, oh, they, you know, they’re limping now.

As a pet parent, what position are they in? How does he sit on the table? You know, he’s got redness on his lips. Is there a bite block that’s in place? So some of those positioning modalities can affect that quality of life as well.

[00:28:30] >> Molly Jacobson: And those are things that you could take into account for the next session. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the treatment’s too harsh on them. It just might mean he needs a slightly different position.

[00:28:39] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct.

[00:28:39] >> Molly Jacobson: Or maybe more padding, or something else can be done to help.

[00:28:44] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

[00:28:45] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s very interesting.

[00:28:46] >> Jenny Fisher: There are even times, you know, certainly, with experience those technicians, they already know these things. They know they’re not gonna splay a old geriatric Labrador on the, that you don’t do that, right. They know that you don’t put hard elbow, you know, so, but there are certainly, as technicians are learning, that – or if they are human radiation technicians that come over into the veterinary space that don’t know veterinary anatomy, they might not be as aware of things.

And if nobody’s telling them… right? So as the pet parent, what position are they in? What positioning modalities or, you know, are there bite blocks? Is he in an uncomfortable position? All of good, good information for the pet parent to know.

[00:29:29] >> Molly Jacobson: And who’s in the vault? Do you leave the vault when you set up the dog’s anesthesia, push the button and run, or do you stay?

[00:29:38] >> Jenny Fisher: So that’s also a good question. So the first treatment, the first initial treatment, the radiation oncologist, usually a physicist, a veterinary assistant, two veterinary technicians – one to anesthetize the patient and monitor the patient, the other to run the machine and work the machine and set the patient up. So there’s always one person specifically just monitoring anesthesia and monitoring the patient there.

Once the patient is ready to treat, we all leave the room and then dose is delivered from outside of the room. Most facilities have monitoring cameras, so there’s a camera on your pet all the time. They are never without eyes on them, right.

[00:30:16] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:30:17] >> Jenny Fisher: But by law we cannot be in the room, um, when that dose is delivered. So your pet is alone for that period of time. Now that’s why they’re hooked up to monitors. So we can see ECG. And ask those questions, right. As a pet parent: what type of monitoring is in place for my pet during this procedure. Right?

[00:30:35] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:30:36] >> Jenny Fisher: You have every right to ask that. And most, if not all of them, there’s cameras, and literally we can stop the beam and be in the room within seconds.

[00:30:45] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:30:45] >> Jenny Fisher: As long as it takes me to hit a button and get up out of my chair and run inside, we can be inside the room and stop delivery and it’s safe to go in.

[00:30:53] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:30:54] >> Jenny Fisher: But they are technically alone for that period of time.

[00:30:57] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. But as long as the machine’s off, you guys can go in and-

[00:31:01] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely safe to be around. No exposure.

There are older radiation therapy units, the old cobalt units, they had a radioactive source inside the head that had to be exposed. I don’t know that there’s any cobalt still in use, but again, that’s why it’s important to know what type of machine is being used because those old cobalt units do have active sources in them.

[00:31:23] >> Molly Jacobson: So do you all worry about your own radiation exposure when giving these treatments?

[00:31:28] >> Jenny Fisher: Not with this type of treatment. So when we talk about radiation, we talked about diagnostic and therapeutic. With diagnostic radiation, and therapeutic, we have a little monitoring badge, what’s called a dosimetry badge, that measures our exposure. It is much more likely to get higher levels in diagnostic radiology with x-rays, than it is within the radiation therapy vault, because there’s only that radiation generated when they’re in the room and we’re not in the room and we’re not in the field.

A lot of the times, if people are not using proper immobilization, they might be in the room when they’re taking those x-rays. We know that people unfortunately use bad practice and may have a hand or, or something, so they’re having direct exposure. So much different. Much more possible in diagnostic radiology than in therapeutic.

[00:32:19] >> Molly Jacobson: So like in a typical vet practice, almost everybody has an x-ray machine, and depending on how they’re working and how safe they’re being, they might be more exposed than you are as someone who’s actually administering radiation as a treatment.

[00:32:33] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

I’ve also been educated on the physics and the, the, I mean, I’ve had full range safety training.

[00:32:41] >> Molly Jacobson: Because of your VTS oncology training.

[00:32:44] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. And majority of people haven’t, right?

[00:32:47] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:32:48] >> Jenny Fisher: And so, uh, yeah, it’s the whole safe, we could do three series on safety in veterinary medicine alone.

[00:32:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, maybe we will.

So in terms of the day of the treatment, owners should be fasting their dogs because they’re gonna be under anesthesia, and then they should be thinking more about the, that first day, it’s like 45 minutes maybe.

[00:33:09] >> Jenny Fisher: Yep. Little bit longer.

[00:33:10] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. But the treatment is just five to seven minutes each time, but the prep for the first time is longer.

[00:33:17] >> Jenny Fisher: That is correct.

[00:33:18] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. And then, is this usually, my memory is that it’s five days a week for several weeks usually for these protocols?

[00:33:25] >> Jenny Fisher: For, if you’re using a traditional linear accelerator with that curative intent, it is daily for four to six weeks depending on the, on the treatment protocol.

[00:33:34] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. So you’re gonna be going into the vet, anesthesia, and then monitoring your dog afterwards for anesthetic issues, side effects that might come up.

[00:33:43] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely. And I’m actually doing, um, a podcast about radiation therapy anesthesia specifically, and how it is very different than surgical anesthesia. And so I don’t think that’s until September. It’s, it’s coming in a bit, but.

[00:33:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:33:56] >> Jenny Fisher: It’s a really great topic as well, because when we hear anesthesia, we think my pet from his spay and he was zonked for two days. So we immediately have that, oh, I don’t want them to do that. Right?

[00:34:06] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:34:06] >> Jenny Fisher: So again, the education of – the goal, when we’re anesthetizing for radiation therapy, we’re not going for a surgical plane of anesthesia, right? I don’t want them that deep. I want them to be still, not remember what’s happening, right, I want that amnesia effect.

[00:34:21] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:34:21] >> Jenny Fisher: And then I want them to quickly recover, right? Because they need to go home, be at home. This is, the goal is to be at home, not in the hospital.

[00:34:29] >> Molly Jacobson: Sort of like when you get a dental procedure that requires a little anesthesia. You may not, like you recover very quickly. They don’t want you to stay in their office.

[00:34:37] >> Jenny Fisher: Yep. I always tell people your colonscopies. You know.

[00:34:40] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. Yeah.

[00:34:41] >> Jenny Fisher: It’s a great way to think about kind of your radiation treatments, because it is typically going to be not as painful. The radiation itself is not painful at all. And as long as we are not putting them in a painful position based on their anatomy or their tumor, then they maintain, the majority, really, really well, and then we get them up very, very quickly. So we use a short acting induction agent that puts them to sleep, so something like Propofol, um, that we will use.

And then we intubate them or put in a tube in their airway. So that’s something we monitor over time, if their throats are getting sore, they’re coughing, we may do ice chips or things like that, or even some an antiinflammatories. The majority of facilities – not all facilities – majority of facilities, then hook them up to a gas, um, an inhalant gas, that will keep them at a certain level of being anesthetized.

[00:35:32] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:35:32] >> Jenny Fisher: So those two are very short acting drugs. So once those two drugs are worn off, 20 minutes, 30 minutes after they’ve been delivered, there is no residual drug in the system because we didn’t do anything that was painful or stimulating. So very different goal of the anesthesia, and our technicians play a vital role in educating these pet parents that I know you’re freaked out when you hear the word anesthesia, it’s not gonna be the same experience.

And if it is, then we need to know about it, cuz we’re not doing it right.

[00:36:03] >> Molly Jacobson: That is really helpful because honestly, all these years of thinking about dog cancer every day, I have always had the same anesthesia, like for surgery, in my mind, or like daily anesthesia, that sounds like a lot. But it’s not, it’s like a colonoscopy anesthetic. It’s very light. You wake up really quickly and you feel fine later.

[00:36:23] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. Yeah.

[00:36:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So the dog is going in for daily treatments, they may or may not like going for daily treatments, but at least when they’re out, they’re up, they’re around, they’re eating, interacting.

And if they’re not, you tell the tech and they make adjustments.

[00:36:38] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely. Absolutely.

[00:36:40] >> Molly Jacobson: Fantastic.

[00:36:40] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

[00:36:41] >> Molly Jacobson: So in terms of side effects, other than anesthesia, what are we looking at like short term and long term? Is there anything that we haven’t talked about short term and then what are the long term side effects you might see?

[00:36:52] >> Jenny Fisher: So there are, um, you know, those rapidly dividing cells like we talked about, inducing tumors down the road. There are two different categories of radiation side effects that we talk about and that’s acute or delayed. And the acute effects are going to be the effects in the radiation field specifically. So if you have a patch of hair loss on the back and the head is being treated, the radiation did not cause the hair loss on the back, okay?

[00:37:19] >> Molly Jacobson: ‘Cause it wasn’t in the field of radiation.

[00:37:21] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. ‘Cause it was not in that field. But what we see locally are things – inflammation. So mucositis of the oral cavity, if it’s radiated, dermatitis, so redness, erythema, itchiness. It typically can present like a sunburn. And I’d say anywhere from a grade zero to a grade three sunburn.

[00:37:42] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:37:43] >> Jenny Fisher: Some of these side effects, which are temporary, they will heal once the radiation has been completed, the majority of them will heal once radiation has been completed. Uh, but they need to be managed during that period of time. So keeping them clean, keeping the pet off of them, whether that’s with an e-collar or a bodysuit or a t-shirt or boxer shorts or, or wherever. Keeping them from attacking or licking or traumatizing that site.

[00:38:08] >> Molly Jacobson: Do those usually show up quickly, or later, or like if you’re doing four weeks, are they showing up the first day or is that redness and sunburn, is that like the next week? When do they show up?

[00:38:19] >> Jenny Fisher: It’s gonna be associated with the dose that that tissue has received.

[00:38:22] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:38:22] >> Jenny Fisher: So if you’re doing those palliative courses and receiving those larger doses, you can certainly see those effects week two, week three. If you’re doing that curative intent where those doses are smaller per fraction, you may be three weeks into therapy before you start seeing those massive effects.

[00:38:40] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:38:41] >> Jenny Fisher: So depends on that dose per treatment.

[00:38:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So it’s the cumulative amount of radiation that area has received, not how many times it’s received radiation.

[00:38:51] >> Jenny Fisher: That is correct.

[00:38:53] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:38:53] >> Jenny Fisher: That is correct. And then the other category of effects, that delayed effects. So those are tumors that are caused or induced by radiation. So years down the road, and those again are gonna be more likely or more accustomed to happen in those patients that receive those larger doses over fewer fractions of treatment.

So I have seen a handful of them. One of them that comes to mind and that I talk about all the time was a, a little dog named Brandy. And Brandy was, we saw her at one of the universities where I was, but eight years prior to when I met her, she had been treated for a primary brain tumor at another university on the west coast.

So she unfortunately developed a radiation induced tumor of her skull, but it was eight years after she was treated for a brain tumor. So, we didn’t expect Brandy to, you know, live long enough to where that – it’s amazing and wonderful that she did, but certainly we can see those delayed effects too. So our acute effects, they will heal.

They get better. The skin looks beautiful. Those delayed side effects, they do not heal. Those are secondary tumors caused from the treatment itself and there’s no sustainable treatment for those.

[00:40:07] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. And are there any other delayed effects? Like anything else that could happen, skin changes or I don’t know, hair loss or…?

[00:40:16] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely. So there’s a couple of things that we can see. So hair loss, so alopecia in the field, as well as we can see something that’s called leukotrichia in the field. And this is where we actually get a hair coat color change in the field. So let’s say it’s a black Labrador, they have a treatment field, that hair will fall out a lot of times, you may see that dermatitis that you treat. That skin is then gonna heal and the hair starts to grow back. The majority of the time it comes back white in the treatment field.

[00:40:46] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:40:47] >> Jenny Fisher: So, it’s always kind of a, a joke in the radiation side of things that if the field’s not correct, we’re all gonna know it at some point, because the leukotrichia will tell the story, right? So, you know, a lot of times, if you see a pet that’s had cancer treatment and you may see solid hair color, but one spot of white, a lot of times that may indicate their previous cancer treatment.

[00:41:09] >> Molly Jacobson: Interesting.

Any other delayed side effects that tend to crop up – and, and these are happening months later, right? Like a long time later.

[00:41:18] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. You know, along with that secondary tumor formation in that delayed group, we can see things like tissue necrosis, bone necrosis.

[00:41:26] >> Molly Jacobson: Necrosis, meaning dying off, like sloughing off.

[00:41:30] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct.

[00:41:31] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:41:31] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. When the pendulum swings, right. And that’s that really unfortunate side of cancer, the, the treatments, when the treatments, you know, make things worse. That’s never anybody’s goal and that’s not what we wanna see, but it is certainly something that’s possible.

[00:41:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. And when do those delayed effects typically come up? I personally have spoken to dog lovers who are in total panic because their dog’s hair is coming in white and they don’t know why and it’s in the area and they think it’s a tumor sign, and then they go to their oncologist and say, no, that’s a delayed side effect.

[00:42:03] >> Jenny Fisher: Yeah.

[00:42:04] >> Molly Jacobson: And it shows up much later, but how much later?

[00:42:06] >> Jenny Fisher: So we can see that anywhere up to a year-

[00:42:09] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:42:09] >> Jenny Fisher: -after therapy. So you may have a period where you get no hair growth and it just kind of sits there for a while, which probably really freaks them out, and then all of a sudden here comes some white hair when it wasn’t white before, you know what is happening? But that’s very common. Now, those really delayed side effects that we talk about, like the bone necrosis, tumor formation, those we see years down the road.

[00:42:31] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:42:32] >> Jenny Fisher: Right. Unless it’s some super high dose of radiation in a really large tumor, a lot of times we, we don’t see those until years down the road.

[00:42:40] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

Does radiation in any way affect the immune system?

[00:42:44] >> Jenny Fisher: So the radiation itself, and from a physiologic or physiology standpoint, I don’t know the actual mechanics of the true total effect on the immune system – my personal belief is that it is the chronic anesthesia that affects their immune system more than the radiation delivery itself because that is such a specific, targeted type of therapy.

You know, certainly with chemo, we see that, that immune effect, but the chronic anesthesia, you know, anytime we are causing an imbalance in the metabolic artwork that is the body, we can certainly see those different kind of effects. So I personally believe, and I don’t have any data to put this on top of, uh, that it’s the chronic anesthesia that may affect that immune homeostasis more than the radiation itself.

[00:43:33] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

What cancers do you usually treat with radiation?

[00:43:37] >> Jenny Fisher: So with radiation therapy, we typically treat soft tissue sarcomas. So things of the cartilage or bone. A lot of times they may be things that are nonresectable, so if something located maybe on a rib or in the jaw that that is unresectable.

[00:43:53] >> Molly Jacobson: Meaning it can’t be cut out with a scalpel. It can’t be surgically removed.

[00:43:57] >> Jenny Fisher: Correct. It’s, it’s unable to have that surgical resection. So we treat specifically lots of osteosarcomas. So common primary bone tumor in large breed dogs that we see very, very commonly.

We treat a lot of anal sac tumors. So female dogs have a higher predisposition for developing anal sac tumors. So in those little anal glands on, on each side of the anus, uh, we treat a lot of those, um, with radiation therapy as well. We can treat bladder tumors. And then other soft tissue sarcomas as well.

So things that are just on the skin, but that are sarcoma related. We don’t treat diseases in the abdominal cavity with radiation therapy, it’s usually going to be on the skin, in a long bone, and sometimes we can treat things within the chest. But there’s a lot of normal tissue in the abdomen and in the chest that doesn’t like radiation so we don’t see those areas treated very commonly.

[00:44:53] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So typically it’s in a limb where you’re not worried about organ damage or it’s in a very delicate area, like the head, but where you can be sure you’re really only getting that tumor.

[00:45:03] >> Jenny Fisher: That is correct.

[00:45:04] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. All right. As we wrap up here. Is there anything that you really think people need to know about radiation treatments for dog cancer that we haven’t covered?

[00:45:15] >> Jenny Fisher: Not that we haven’t covered. I think perception is the biggest one because you know, perception is reality and a lot of humans have had their own reality with cancer treatment and with radiation therapy. And so they might be coming from a different place. So educating them and really listening to them about their concerns and educating them on how it is very different within the veterinary space and what our goals are, that our goals are, are also going to be a bit different than what they go after in the human space as well. So uh changing perception.

[00:45:45] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. So someone who’s listening and has been told that radiation is an option for their dog and might be thinking, my aunt had radiation and she hated it, and all of these things happened, and I don’t want that for my dog. Instead of assuming the same thing would be true for this case, for their dog and for this radiation treatment, to really make sure they ask the questions.

This is what happened to my aunt, is that what you expect to have happen, and get that teased out so that they can be more accurate in understanding what’s going to happen in a radiation course.

[00:46:17] >> Jenny Fisher: And to be committed. It’s hard to be committed to something that you’re scared of.

[00:46:20] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah.

[00:46:21] >> Jenny Fisher: So if we can ease some of those fears and they can be more committed to their pet’s treatment, it’s gonna make the pet respond even better if they’re, if they’re fully on board, if they’re in the right head space for that.

[00:46:32] >> Molly Jacobson: Well that is always the case, right? It’s our attitude that our dogs pick up on more than anything else. And so if we think this is a good thing, then they will be much more comfortable and therefore accept it better and heal better.

[00:46:45] >> Jenny Fisher: And I can guarantee the majority of oncology technicians take care of their radiation patients and try to make it as fun as possible when they come to the hospital. If, you know, if they can have treats, or if they have specific treats bring them with them, because typically the first thing that we’re giving them when they’re awake is treats or they have a toy or a ball. We want them to associate seeing us every day with happy and treat. We certainly wanna keep the mood reflective of a healing environment.

[00:47:12] >> Molly Jacobson: Well, that’s a great tip. And once they’re up and about, how long does it take for us to see our dogs again?

[00:47:17] >> Jenny Fisher: Usually about 30 minutes to 45 minutes. So not that long. We wanna get them back to you as fast as you want them, I promise.

[00:47:23] >> Molly Jacobson: Absolutely. Give them their favorite treats and they’ll see Mom and Dad soon.

[00:47:27] >> Jenny Fisher: Absolutely.

[00:47:28] >> Molly Jacobson: Well, thank you so much for joining us, Jenny Fisher. We really appreciate all of your insights. I hope maybe you’ll come back and talk a little bit about surgery and chemotherapy.

[00:47:40] >> Jenny Fisher: I would love to. I can talk about cancer for days and days, so you just let me know.

[00:47:45] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. We will do that. Thanks again.

And thank you listener for joining us. I hope you found today’s conversation as interesting and informative as I did. I really did not understand how quick radiation is. I really didn’t understand that the anesthesia used is much lighter and less extensive and grog-inducing as it is when it’s used in surgery. And I’m fascinated by the use of radiation as pain relief for immediate pain relief in dog cancer. I think that is really, really interesting.

I’m gonna take radiation treatments a little bit more seriously in the future as people talk about them in our support group on Facebook – that’s Dog Cancer Support if you’re not already a member.

I hope that you found today’s show interesting. If you’re looking for the show notes with all the links and all the things that we talked about, they’re on dogcanceranswers.com. And if you ever have any questions for us about this or any other topic, don’t forget to call our Listener Line at (808) 868-3200.

I’m Molly Jacobson. And for all of us here at Dog Podcast Network, I’m wishing you and your dog a very warm Aloha.

[00:49:04] >> Announcer: Thank you for listening to Dog Cancer Answers. If you’d like to connect, please visit our website at dogcanceranswers.com or call our Listener Line at (808) 868-3200.

And here’s a friendly reminder that you probably already know: this podcast is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It’s not meant to take the place of the advice you receive from your dog’s veterinarian. Only veterinarians who examine your dog can give you veterinary advice or diagnose your dog’s medical condition. Your reliance on the information you hear on this podcast is solely at your own risk.

If your dog has a specific health problem, contact your veterinarian. Also, please keep in mind that veterinary information can change rapidly, therefore, some information may be out of date.

Dog Cancer Answers is a presentation of Maui Media in association with Dog Podcast Network.

Hosted By

SUBSCRIBE ON YOUR FAVORITE PLATFORM

Topics

Editor's Picks

CATEGORY