EPISODE 169 | RELEASED May 30, 2022

ELIAS Cancer Immunotherapy for Dogs | Tammie Wahaus

Bone cancer is a brutal disease, but ELIAS Animal Health has an immunotherapy protocol that is making headway.

SHOW NOTES

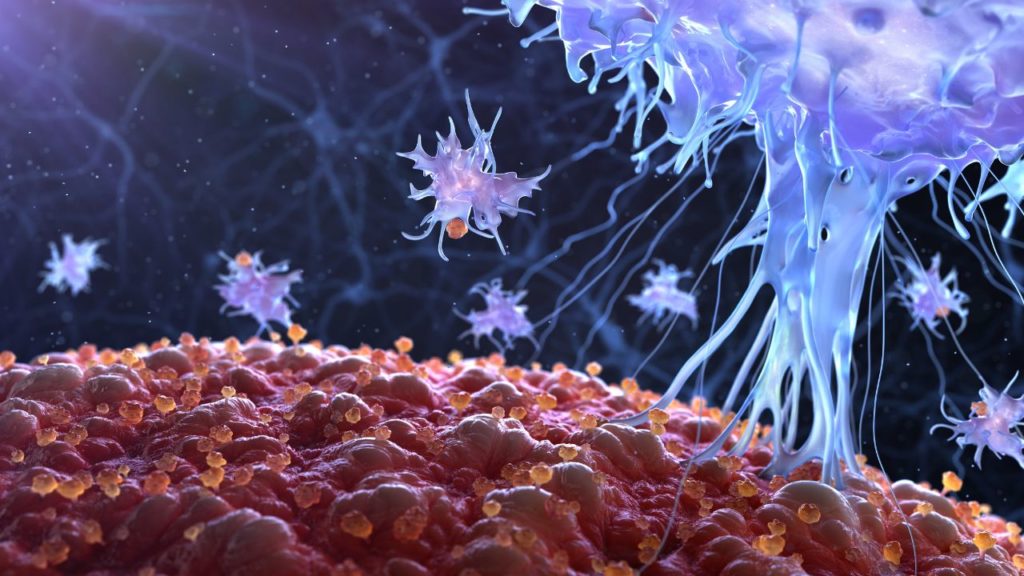

Immunotherapy is becoming increasingly important in human cancer treatment, and more and more companies are bringing this technology over to dogs! The ELIAS Cancer Immunotherapy (ECI) system is still experimental, but they are already seeing positive results in the approximately 200 dogs that have been treated so far.

CEO Tammie Wahaus explains how ECI works, the role of a healthy immune system in successful immunotherapy, and why they chose to focus on osteosarcoma first. A randomized pivotal trial comparing dogs treated with ECI to dogs treated with carboplatin chemotherapy will be complete later this year, and we will be following those results.

Links Mentioned in Today’s Show:

Canine Osteosarcoma Clinical Trial

[00:00:00] >> Tammie Wahaus: And so we first tell the immune system, this is what you’re looking for, generate some soldiers, known as T cells. We’ll take those T cells out of the body, we’ll grow them up and activate and expand them in our manufacturing facility, and we’ll give you back an army.

[00:00:20] >> Announcer: Welcome to Dog Cancer Answers, where we help you help your dog with cancer. Here’s your host, James Jacobson.

[00:00:28] >> James Jacobson: Hello friend. If you’ve been listening to Dog Cancer Answers for awhile, you know that a lot of veterinarians are awfully excited about immunotherapy and its promise in treating dogs with cancer. Today, we are speaking with Tammie Wahaus. She is the CEO of a biotech company located in Kansas City called ELIAS Animal Health.

They have been focusing on a new approach to immunotherapy using a technology called ECI. Tammie Wahaus, thank you so much for being with us today.

[00:00:59] >> Tammie Wahaus: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to join you.

[00:01:01] >> James Jacobson: So let’s start off with a basic question. What does ECI stand for?

[00:01:08] >> Tammie Wahaus: So ECI stands for the ELIAS Cancer Immunotherapy.

[00:01:13] >> James Jacobson: Okay. And that is the basis of what you all are doing and applying to dogs.

[00:01:19] >> Tammie Wahaus: That’s correct. It’s our foundation technology that we have conducted clinical trials in, in dogs. It’s been brought over from a human health company who’s trying to advance it for humans as well. And now we’re in the process of building some additional technologies around it to further improve treatment outcomes.

[00:01:39] >> James Jacobson: So this is quite the trend these days, to really partner with, or to basically have an animal health spinoff from human research, right?

[00:01:50] >> Tammie Wahaus: Correct. Yes. It was discovered, I don’t know, 10 or so years ago, that canines actually share so much of the genome with humans and the disease behaves, in many cases, similarly to how cancer behaves in humans albeit in many cases it’s much more aggressive in dogs. So the scientific community began to pursue, can dogs be a good indicator of how therapeutics will work in humans.

[00:02:26] >> James Jacobson: So you come at this, you’re in the Kansas City area, which is sort of the center in America for veterinary health. That’s fair, right?

[00:02:36] >> Tammie Wahaus: That’s correct.

[00:02:37] >> James Jacobson: And there’s a lot of venture capital and there’s a lot of resources available to developing technologies in pharma for animal health.

[00:02:46] >> Tammie Wahaus: Correct. We have, I think it’s said we have one third of the global animal health assets located here in the region that they call the animal health corridor.

[00:02:55] >> James Jacobson: So right there in the center of the country. And you come at this, not from a medical background yourself but from an accounting background?

[00:03:04] >> Tammie Wahaus: Correct, yes.

[00:03:05] >> James Jacobson: Tell me about that. That’s kind of interesting.

[00:03:07] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. My undergrad was in business and finance with an accounting emphasis, and went into public accounting right out of college and spent, I think, 20 years or so in public accounting, one of the best training grounds for learning how a business operates and how different industries function. So I think it prepared me well for doing a number of other things, including, you know, leading the animal health company.

[00:03:37] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

So what you’re doing is immunotherapy. And at this point there must be over a dozen different companies working on immunotherapy for dogs with cancer.

[00:03:48] >> Tammie Wahaus: There are a number of companies that are trying to advance technologies and they range the spectrum from vaccines to T cell therapies to, you know, some of the oncolytic viruses.

[00:04:01] >> James Jacobson: Okay. So what is unique about what ELIAS is doing?

[00:04:04] >> Tammie Wahaus: So our technology really leverages – you know, we use the word harnesses – the power of the patient’s immune system. One of the things that the immune system is particularly capable of, which is why we all still exist, is constant surveillance of the body for foreign threats. So that’s the role of the T cells. The reason that we believe that cancer is not terminated naturally by the immune system is that it looks too much like itself, right?

It’s a mutation of normal cells, and just like the body doesn’t, unless you have an auto-immune disease, doesn’t attack itself, the same happens with cancer. So what we need to be able to do, is in a very profound way inform the immune system what it should be looking for. So what we do is we pair a vaccine that is derived from the patient’s own cancer with an adoptive cell therapy. So what the vaccine does is it says to the immune system, okay, here’s this cell, it’s different than self, so you should be alerted. So that alerts the immune system and the T cells then begin to surveil the body for those cancer cells. But what the immune system needs – because vaccines aren’t typically known for curing disease, right? We think of vaccines as preventing disease.

When, when we all encountered COVID we didn’t go get a COVID vaccine then because we needed a more robust treatment. So what we do is we then pair the T cell therapy, which is the more robust treatment, with that vaccine. And so we first tell the immune system, this is what you’re looking for, generate some soldiers, known as T cells.

We’ll take those T cells out of the body, we’ll grow them up and activate and expand them in our manufacturing facility, and we’ll give you back an army. Right? So we collect a platoon of soldiers, we give back an army.

[00:06:22] >> James Jacobson: So quantify that, because I mean, and this process is really interesting ’cause there’s so many stages. Even before you get the T cell, you’re starting with something very personalized from the dog.

[00:06:32] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yup.

[00:06:33] >> James Jacobson: And then you a few weeks later, I mean, what’s the progress of time?

[00:06:37] >> Tammie Wahaus: Right. Right. So the treatment regimen is, we can focus on osteosarcomas so-

[00:06:42] >> James Jacobson: Well we can focus ’cause that’s what you guys exclusively focus on at this point.

[00:06:46] >> Tammie Wahaus: At this moment, most of our data is in osteosarcoma.

So a week after surgery, the patient will get their first vaccine followed by two additional boosters at weekly intervals. So weeks one, two, and three, they’re going to get a vaccine. Then we wait two weeks, and in week five, the patient goes in for a T cell harvest or mononuclear cell collection. So they go into the vet to have those cells that we primed, collected.

And then in week six, we turn back around the activated killer T cells. So it’s about six weeks to get all the way through the T cell infusion. And then we follow that with a low dose interleukin 2 to continue to boost the immune system once those T cells are in there. So we kinda keep those T cells happy and proliferating for a couple of weeks until they get established in the body. And then the patient is done with treatment.

[00:07:47] >> James Jacobson: So when you say you go from a platoon to a whole, what was the, armament or?

[00:07:52] >> Tammie Wahaus: To an army, yeah.

[00:07:53] >> James Jacobson: An army. So quantify that. How much more, how many more T cells are you adding to the dog?

[00:08:00] >> Tammie Wahaus: Oh, it’ll be billions.

[00:08:02] >> James Jacobson: Billions. Okay. And the hope of having all of those T cells is what?

[00:08:08] >> Tammie Wahaus: Well, those T cells now have been informed and are able to recognize the cancer cells. They will traffic to wherever the tumor cells are because that’s their job. Again, they’re surveilling the body and they’re looking for something, and these cells are looking for the cancer cells. So they’ll traffic to the tumor and begin to cause the tumor cells to die. And they do that through a number of mechanisms which are, are really complicated and would need to be the topic of a scientific presentation.

[00:08:39] >> James Jacobson: And neither of us are doctors or PhDs. So how many dogs have you done this with at this point?

[00:08:45] >> Tammie Wahaus: So we have treated over 200 dogs.

[00:08:47] >> James Jacobson: Okay. And this is under some sort of temporary FDA, what’s the regulatory environment that you guys are working within?

[00:08:56] >> Tammie Wahaus: Sure. That’s a great question. Our particular product is regulated by the USDA Center for Veterinary Biologics.

[00:09:03] >> James Jacobson: Because?

[00:09:05] >> Tammie Wahaus: Because it’s vaccine oriented and it is a biologic for use in animals.

[00:09:11] >> James Jacobson: Let’s tease that apart ’cause I think that’s one of the more interesting things that a lot of listeners, when they learn about, that, it’s a little confusing, the first time I heard about it. So most pharma, you know, if for animals, is governed by the US Food and Drug Administration, the Center for Veterinary Science. But Food-

[00:09:29] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah, so-

[00:09:30] >> James Jacobson: No?

[00:09:31] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah, let me, let me-

[00:09:32] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:09:32] >> Tammie Wahaus: Just let me try to help there.

So if you think about the, the FDA, FDA regulates all human therapeutics, all human products, right?

[00:09:39] >> James Jacobson: Right.

[00:09:40] >> Tammie Wahaus: Within the FDA, they have the Center for Veterinary Medicine, CVM, which is focused on drugs, and the USDA then handles biologics. So ours is a biologic.

[00:09:53] >> James Jacobson: And the reason the USDA…?

[00:09:55] >> Tammie Wahaus: It’s just how the regulations are written.

[00:09:57] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:09:58] >> Tammie Wahaus: And, you know, new products when they come on the market, you first have to determine – see, even within the FDA, on the human side, there are two divisions of the FDA on the human side, the Center for Biologics and the Center for Drugs.

[00:10:11] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:10:12] >> Tammie Wahaus: And so drugs and biologics are a natural split. And in the case of the animal products, remember the USDA was established long before the FDA was established and they were regulating, you know, any number of things.

And they do the regulation on a lot of the, you know, they, they manage the food supply, et cetera. But the Center for Veterinary Biologics is where our product. So when you have a product that you’re going to bring to market, one of the first things you have to do is go read the rules of the two agencies and figure out who is your regulator.

[00:10:47] >> James Jacobson: Okay. So does USDA regulate all, in this case, companion animal vaccinations?

[00:10:53] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yes.

[00:10:54] >> James Jacobson: All, okay. I didn’t know that.

[00:10:56] >> Tammie Wahaus: Well, if, to the extent that they’re a biologic.

[00:10:58] >> James Jacobson: Okay. Maybe we got to tease apart that term.

[00:11:00] >> Tammie Wahaus: It all hinges on biologics.

[00:11:01] >> James Jacobson: What is a biologic?

[00:11:03] >> Tammie Wahaus: Oh, we, we might need to schedule a new podcast for that. That’s about a 50 page document that was published, uh, there’s a very long document that was written about 15 years ago to help people understand.

[00:11:17] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:11:18] >> Tammie Wahaus: If it’s this, then it goes here. If it’s that, then it goes here. If it’s made in this way, it goes here. So it’s very complicated, that’s where you call an expert.

[00:11:29] >> James Jacobson: I got it. Okay. And the reason I want to get into a little bit of this is, it’s kind of heady stuff, but I think it’s useful for listeners to understand and appreciate how fast companies like yours are able to move because they’re not constrained by the normal Food and Drug Administration process. But the hope is if you guys are successful in doing this with dogs, at that point, the companion company that you’re working with, where this technology was really developed, will be able to become an FDA regulated human drug therapy.

[00:12:07] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. So when we focus on the dogs, you know, first of all, particularly in cancer, there aren’t very many approved products for cancer. Right.

[00:12:15] >> James Jacobson: Very few. Just a handful. Yeah.

[00:12:16] >> Tammie Wahaus: But in humans, there are a lot of approved products. So in human world, you can’t test a product without first giving the patient the product that’s already approved. So let’s say it’s carboplatin. You can’t test an immunotherapy on a patient without also offering them that standard of care carboplatin. In dogs, where there aren’t any approved products, you don’t have that same constraint.

And why is that important? It’s particularly important for an immunotherapy because oftentimes what you have is, you know, the chemotherapeutics interfere in many cases with the immune system. We want a strong, healthy immune system. And if the patient is on some other sort of therapy where, in addition to, you know, damaging cancer cells, it’s also damaging the immune system, that is not helpful.

[00:13:15] >> James Jacobson: It’s poisoning the overall body with the hope of, you know.

[00:13:18] >> Tammie Wahaus: Right. Right. So you have that advantage if you’re looking at a cancer in dogs that doesn’t already have a product approved, then you aren’t having to come in after that.

[00:13:27] >> James Jacobson: Got it.

[00:13:28] >> Tammie Wahaus: You get to treat a dog when he’s first diagnosed. A lot of times in human trials, you know, you have to fail three types of therapy before you can be entered into a clinical trial, so that’s one. Secondly, in dogs, what’s their average lifespan? We say one year is equal to seven years?

[00:13:46] >> James Jacobson: We’ll say seven. But we know that’s not exactly right.

[00:13:49] >> Tammie Wahaus: So many of the cancers in dogs actually also progress more quickly than they do in humans. So clinical trials are shorter. Because like an osteosarcoma dog, if all you do is amputate to remove the primary bone tumor, he’s probably still only going to live 120 to 160 days. Whereas humans with osteosarcoma, they may live years. So you have a patient who has a very short timespan if you don’t intervene.

So then when we intervene, we still get an answer. In osteosarcoma, right now, the current technical standard of care, even though it’s not an approved product for dogs, is carboplatin. Because the veterinarians have had to find something that they could use. And the carboplatin does extend life in a dog.

[00:14:47] >> James Jacobson: After amputation.

[00:14:48] >> Tammie Wahaus: After amputation. If you can get them before they have lung mets, typically you’re getting 270 to 320 days.

[00:14:58] >> James Jacobson: Which again, based on human things, that’s that’s seven years.

[00:15:01] >> Tammie Wahaus: Right? Right? So that is the advantage. Unfortunate for the dog, right? But we are getting answers much more quickly on whether therapeutics are working-

[00:15:11] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:15:12] >> Tammie Wahaus: -than what can be done in humans. And it was exciting for us, in our first clinical trial that we ran, we had 14 dogs that were fully evaluable and, you know, we had a median survival time of 415 days.

[00:15:26] >> James Jacobson: Okay. Significant.

[00:15:27] >> Tammie Wahaus: Which was very, yeah, pretty astounding compared to – and these dogs did not get carboplatin. They had no chemotherapy, it was just amputation plus our therapy. And that data was combined in the package that went to the FDA for the human side to say, we would like to get fast track designation.

[00:15:48] >> James Jacobson: Got it.

[00:15:48] >> Tammie Wahaus: And they were successful in getting fast track designation. Now they have to raise the capital.

[00:15:52] >> James Jacobson: As a result of that 14 dog study.

[00:15:55] >> Tammie Wahaus: Absolutely.

[00:15:56] >> James Jacobson: And have they raised the capital on the human side yet?

[00:15:59] >> Tammie Wahaus: They’re working on it.

[00:15:59] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:16:00] >> Tammie Wahaus: Capital is very hard to raise.

[00:16:02] >> James Jacobson: Uh, it changes right? Sometimes it’s, sometimes it’s really easy. Sometimes it’s really hard. And I mean, you guys are focusing on osteosarcoma, which admittedly is a lot more common in dogs than in people. Since you’re so focused really on bringing this into the human market, why osteosarcoma?

[00:16:24] >> Tammie Wahaus: One of the unique advantages of the way we approach this therapy, which is to start with the patient’s tumor itself, that lends this product easily adaptable to other cancer types.

So the question that we were trying to answer is does this therapy work in a highly metastatic aggressive form of cancer? So we weren’t really trying to answer the question, does it work in osteosarcoma? We were answering the question, does it work in a highly metastatic disease that is very aggressive? And osteosarcoma was the pick for that because it fits that criteria.

[00:17:08] >> James Jacobson: So then the thinking is if it works in a highly metastatic cancer like osteo, then it’ll work in one that is less metastatic.

[00:17:16] >> Tammie Wahaus: Correct.

[00:17:16] >> James Jacobson: And it’ll work across the board. So you say like, you know, oftentimes carboplatin is being used right now for dogs with osteo after amputation, distinguish that from, you know, what a dog’s side effects may be on traditional chemo, versus on your therapy.

[00:17:33] >> Tammie Wahaus: You know, we all unfortunately know a little too much about the side effects of chemotherapy in humans. It’s difficult for dogs to report, right, exactly how they’re feeling, but what they have done in veterinary medicine is they have found a dose of carboplatin that is tolerable in dogs. Does not make their hair fall out. They might lose whiskers, but you know, they don’t lose their coat. It is tolerable, they may, you know, have neutropenia, and those types of disorders while they’re undergoing the treatment. And they-

[00:18:09] >> James Jacobson: Neutropenia is?

[00:18:10] >> Tammie Wahaus: I’m going to have to skip that one.

[00:18:11] >> James Jacobson: We’ll skip. Okay. We’ll put it in the show notes.

[00:18:14] >> Tammie Wahaus: There you go. Just because you do want the medical answer, not Tammie’s layman’s interpretation.

[00:18:19] >> James Jacobson: My producer says low white blood cell count. There you go.

[00:18:23] >> Tammie Wahaus: There you go. Thank you. Um, but they have found a dose that, that doesn’t make dogs as sick as humans get. But we don’t treat dogs. With humans, that human is making the choice. Take me to the brink of death in the hopes that that will be enough for me to overcome this cancer.

And that’s not how they can approach the dogs, and higher doses of the carboplatin don’t actually extend the life any longer. So they have settled in at this dose. But you still get those side effects. With our treatment, our dogs had a, they typically at the injection site for the vaccine, they’ll get a little redness, irritation, just like they’re getting, you know, for any other vaccination.

Occasionally they’ll be a little bit lethargic for 24 hours. Nothing of any real concern with the vaccine. Apheresis day is a, is a long, you know, arduous day for them, very tiring, but they don’t have side effects from it. And then the T cell infusion, the osteosarcoma dogs have tolerated the T cell infusion quite well.

And that’s actually the place in our therapy where we’re asking veterinarians to be vigilant because we’re putting in an army of killer T cells that are intent upon killing cancer. So, if you’re going to have a reaction to this therapy, it’s going to occur likely around the timing of that T cell infusion or within, you know, 24 to 48 hours after.

[00:19:51] >> James Jacobson: And what kind of side effects do you see once that army is released?

[00:19:56] >> Tammie Wahaus: We typically see, um, nausea, a little bit of lethargy, primarily gastrointestinal in nature, maybe a vomiting, maybe a diarrhea, pretty mild. We’ve had, you know, very low grade side effects. They’re very transient for the most part. Required no medical intervention.

But what we are asking them to watch for – we know in humans that the CAR T therapies and the TIL therapies, which have some similarities to what we’re doing, we know that those therapies can produce what is called cytokine release syndrome. And we’ve also seen some similar things, you know, with, actually COVID infections. But it’s essentially, you know, the immune system on hyper activity and then that becomes destructive, right? So that’s what we’re watching for. We don’t see it often. We see it rarely. It can be treated with a dose of steroids. But we do ask the animals to stay in the hospital for the day. So come in and get your T cell infusion in the morning, stay for the rest of the day so you can be under observation, and then, you know, the pet goes home. And the pet owner’s instructed, you know, as long as he’s eating, drinking, and you know, doesn’t get more lethargic, you’re fine.

[00:21:16] >> James Jacobson: Okay. And are more T cells ever administered after that initial, or how frequently do you add-?

[00:21:22] >> Tammie Wahaus: We actually only do the one dose of T cell infusion.

[00:21:24] >> James Jacobson: Okay. So let’s talk about apheresis day, when you are harvesting the little small cadre of soldiers that you then replicate. I didn’t pronounce it correctly. So what is it? And how does that process work?

[00:21:37] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. Well, the whole long-term is called leukapheresis.

[00:21:40] >> James Jacobson: It’s easy for you to say.

[00:21:41] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah, because I’ve been saying it for about six years, right? And we just shorten it and call it apheresis. But it is a process where, if you’ve ever donated blood or donated plasma, you go in, you know, they put in catheters in the veins, particularly a plasma collection, so that your blood is going to leave and be circulated through a machine that is basically a centrifuge.

And then they’re able to separate out the plasma that they’re trying to collect and then everything they don’t need, the blood goes back into the patient. So you have an inline, you have an outline and an inline, and the blood is just going out around and around in the centrifuge. And then the machine is collecting the portion of the blood components that are the target of that collection.

Same thing is happening with the dogs. The veterinary hospitals have the same equipment that is being used in humans. They have the same training. They have a network of, you know, apheresis operators in veterinary medicine. It’s a small community, but they’re very good. And the dog goes in, gets his inlet and his outlet connected. Depending on the dog and the hospital, the dog either may be sedated or he may be anesthetized. They need him to keep still.

Humans, you could say sit, and you will sit for eight hours if you need to. The dog, you know, needs a little bit more encouragement sometimes to sit.

[00:23:04] >> James Jacobson: So obviously, it’s based a little bit on the size of the dog, but how long is the process?

[00:23:09] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah, the process can take anywhere from, you know, two to three hours.

[00:23:14] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:23:14] >> Tammie Wahaus: And then depending on if the dog is anesthetized, you know, it might have to start a little sooner so that he goes under and then he’s got a little bit longer recovery as he comes out of the anesthesia, but usually it’s a couple of hours on the machine. And they’re just basically filtering the blood through, and in this case, collecting the mononuclear cells, that component of the blood is where the T cells are.

[00:23:39] >> James Jacobson: Well, this is fascinating, Tammie. I’m going to take a break right now, but when we come back, I want to talk a little bit about the dollars and cents of this and where you see this therapy moving in the future. We’ll be right back.

We’re back with Tammie Wahaus. Let’s talk a little bit about how much this procedure costs for dog lovers.

[00:24:03] >> Tammie Wahaus: Sure. So historically, uh, for a pet owner who’s paying for what we call current standard of care, which is carboplatin for the osteosarcoma dogs, that you’ve got the cost of an amputation, which is going to vary depending upon the size of the dog, where the hospital is, we all know that there’s geographic price differences, but the any amputation can run anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000. The therapy then when you add on carboplatin and everything that goes with that, a pet owner can pay anywhere from $8,000 to $10,000, maybe higher in some locations.

Our technology, you know, it is new technology and new technology is always more expensive than old technology, but we’re trying very hard to, you know, keep it at a price level that is, you know, not more than 20% higher than what a pet owner would pay for the carboplatin. And the goal here being that if we can produce longer survival times, if we can produce a higher number or a higher percentage probability of survival to one year, survival to two years, that, that it will be a good choice for pet owners.

[00:25:18] >> James Jacobson: So then that would be like about $10,000 to $12,000 for that regimen.

[00:25:22] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. $10,000 to $12,000. And in some locations it could be higher, but we’re trying to keep it in that $10,000 to $12,000 range. And that’s all in, that’s including the cost of what we do, the cost of what the hospital does, the cost of the apheresis.

[00:25:37] >> James Jacobson: Okay. And then I imagine the apheresis is a pretty expensive component of it. How many hospitals across the US, or around the world, are doing this?

[00:25:47] >> Tammie Wahaus: We have worked with over 50 hospitals in the US and we are currently still focused on the US because we’re dealing with live tissues, so we aren’t moving live samples across borders yet. And we currently have about 25 hospitals that are pretty actively treating patients and that’s growing every day.

[00:26:09] >> James Jacobson: Okay. And again, 200 dogs total had this procedure so far?

[00:26:13] >> Tammie Wahaus: Mhm.

[00:26:14] >> James Jacobson: When will you have enough dogs for you and the parent company, that the human side, to know that, Hey, we’ve got enough data collected to know the efficacy and safety of this?

[00:26:26] >> Tammie Wahaus: The 200 dogs that we’ve done, were done in a few different clinical trials. And so we can’t really add them together from an efficacy point of view because, you know, some of them were, it was not all osteosarcoma. We may have had chondrosarcomas, uh, some lymphomas, a number of other, hemangiosarcomas. So what we have done though, is we’ve enrolled a large, what we call a pivotal trial, which is designed to be able to tell us what the efficacy will be. That is a randomized study. We started enrollment in May of 2020, and it took us about a year to enroll a hundred dogs. 50% of those dogs went into the treatment arm where they received amputation plus ECI. The other 50% went into what we call the control arm, which is current standard of care, which is amputation plus carboplatin.

So a hundred dogs contemporaneously enrolled in 10 hospitals, and now we have to follow those dogs for 18 months. So we’re anticipating that we’ll have that 18 month data by the end of October of ’22. So it’s very long, even though that’s short in cancer trials, it seems painfully long to us and to pet owners to have to wait that long to get the data. But that’s what it takes. You’ve got to wait to get the data.

[00:27:54] >> James Jacobson: October ’22?

[00:27:55] >> Tammie Wahaus: October of ’22.

[00:27:57] >> James Jacobson: Okay. Later this year. Obviously, fingers crossed, but what do you hope, or what is the preliminary data indicating?

[00:28:04] >> Tammie Wahaus: So one of the rules in clinical trials is you don’t look at the preliminary data.

[00:28:08] >> James Jacobson: Right. I don’t know.

[00:28:10] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. Yeah. So, um, so we don’t know.

[00:28:13] >> James Jacobson: So you don’t know, but what’s your hope?

[00:28:14] >> Tammie Wahaus: You know, our hope, we, we look at the preliminary trial that we did which showed improvement over carboplatin. Really our hope is to be at least as good as carboplatin, because we think that that demonstrates efficacy, right? We know that dogs who get amputation alone only survive 120 to 160 days. With carboplatin, they get to 280 days, roughly. If we can at least get to there or get close to there, then we’ll know that the product has efficacy.

Like all products, and like all other immunotherapies, it doesn’t work in all dogs. It doesn’t work in all patients. There’s a lot to be learned and we’re continuing to evaluate what are the nuances and how can we address those.

So for an immunotherapy to be effective in a large percentage of patients, you need a healthy immune system. Cancer occurs in older age animals, right? Humans, we know our immune system is not as effective at 60 as it was at 25. True also in dogs. So there are a number of other products that are in development that we think, combined with our therapy, can help overcome some of those limitations, and so to give it an added boost, to give the immune system some additional tools to work with. And so our goal would be to show efficacy in this pivotal trial, which would hopefully support, you know, licensure, and then run additional trials with some added bells and whistles to then push the efficacy further up.

[00:30:00] >> James Jacobson: Can you give us a hint on what those bells and whistles are that boost the immune system while also going after the cancer?

[00:30:07] >> Tammie Wahaus: I can, at least on one, we have in licensed, a technology called an oncolytic virus vaccine, uh, or oncolytic virotherapy. And we’re in the process of working with that. It also is being developed for-

[00:30:21] >> James Jacobson: Can you break that down? Oncolytic virotherapy?

[00:30:24] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. Let me say that slower because I, because if I-

[00:30:28] >> James Jacobson: I can’t break it down, but I can say it slower.

[00:30:30] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. Yeah. So oncolytic virotherapy. And what that is, in, you know, non-technical terms is, it is a particular virus that has been inactivated-

[00:30:42] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:30:43] >> Tammie Wahaus: -but has the characteristics of trafficking to cancer cells. So going to a cancer cell, entering the cancer cell, and causing the cancer cell to die. What that does is then creates a flurry of activity where the tumor is. So let’s say you have a metastasis and you, you have introduced this oncolytic virotherapy in the form of either an infusion or an injection. And that causes cell death at the site of the tumor. That then exposes to the immune system all these-

[00:31:22] >> James Jacobson: Hey, lookout for these.

[00:31:23] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. Hey, look out for these. So that’s pre preparing if you will. And then if we come in, so we’ve already started the process with the oncolytic virotherapy, and then we come in with this very personalized approach that is layering on top of that, and really enhancing, you know, what the oncolytic virotherapy can do by itself, then you should, the theory is, and you know, we have company, the two human companies are actually working together to see if the two technologies can be applied in humans as well.

[00:31:59] >> James Jacobson: Got it. Okay. So when you in-license, where you license from another company, so this is different than the primary, I mean, you’re basically picking and choosing from human medicine and saying, let’s apply this to dogs.

[00:32:12] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yes.

[00:32:12] >> James Jacobson: Quickly. Is there an mRNA component to that? It sounds really interesting.

[00:32:18] >> Tammie Wahaus: Uh, that particular one is not an mRNA component. There are some things being developed and I, I’m not extremely familiar with them. But the other areas that, you know, they’re working on in humans is when they look at, um, we’ve all heard about checkpoint inhibitors.

Well, I hear about it every day, right?

[00:32:37] >> James Jacobson: Well, I was going to say I can’t nod my head on that. What is a checkpoint inhibitor?

[00:32:42] >> Tammie Wahaus: So one of the things that cells have on them are something that we call checkpoints. And as the T cells are surveilling, looking for, you know, cells to attack, they come to a cell and they look at the cell and they say, are you friend or foe? If they’re able to connect with that cell as friend, then they’re like, okay, fine. See ya.

[00:33:06] >> James Jacobson: Carry on.

[00:33:06] >> Tammie Wahaus: If they are unable to connect as friend, right, then we assume foe, let me do what I do, which is I’m going to come in and I’m going to cause that cell to die, that cancer cell. But what happens with the cancer cells is they have these connectors on them that cause the T cell to not recognize them as a foe, right? So it’s what we call immunosuppression, but it basically is causing the immune system to not recognize that cell. What they’re developing now in the scientific community is drugs and biologics that are designed to stop that. So, if we can stop that by using these checkpoint inhibitors, then more of your T cells get to the place they need to get to. So it’s just all about getting more T cells into the places where the cancer cells reside, whether it’s the primary tumor or metastases that have occurred distantly.

[00:34:06] >> James Jacobson: This is fascinating. And I appreciate your clarity at explaining it, especially considering the fact that you studied accounting and finance, and now you’re, here you are with all this medical jargon and, and talking about these types of things.

Did you ever think that you would be doing this type of work when you were, back then when you were like, you know, focusing on finance?

[00:34:27] >> Tammie Wahaus: You know, I didn’t. I always, I had a personal experience. Everyone has a cancer story, right? We all have a cancer story. I have my own list of cancer stories. And when I left public accounting, I started doing some consulting as a, like an interim CFO, for the human health company. And in order to really understand the business, I had to spend a lot of time with the chief scientific officer, a very patient man, great educator, and, you know-

[00:34:57] >> James Jacobson: I got to get the bean counter up on biology.

[00:35:00] >> Tammie Wahaus: And I am fascinated by technology. And I, you know, I do clarify for people, you know, I am not a scientist. What I know is only what I’ve been taught and I can only go so deep, but there are, you know, there’s certain things that are fundamental to being able to understand the work that we’re doing. And he was willing to invest the time in me, and let me pitch it back to him and correct me and, just like we all learn.

[00:35:28] >> James Jacobson: Well, I think that’s kind of, what’s interesting about what ELIAS is doing, because when I look at your, you don’t call it board of directors, you call it the board of, uh.

[00:35:36] >> Tammie Wahaus: Board of managers because we’re an LLC.

[00:35:38] >> James Jacobson: Board of managers.

[00:35:39] >> Tammie Wahaus: But board of directors is fine.

[00:35:40] >> James Jacobson: Okay. When I look at your board, there are a lot of non-veterinarians, non-scientists, but a lot of people who come at this from various approaches, and I think that is somewhat distinctive in the animal health corridor, yes?

[00:35:56] >> Tammie Wahaus: Yeah. You know, when I launched the company, I came at it with a different perspective than most technology companies that get started, right? Life sciences. And I knew that we wanted to, you know, grow the company. And I knew that the science was pretty well established. So, what I wanted was a diverse board of directors who were experts at things I was not an expert at. And so, you know, that I would have advisers that I could call on, right?

So a retired venture capitalist. Uh, marketing experience, sales experience.

[00:36:37] >> James Jacobson: Legal.

[00:36:37] >> Tammie Wahaus: Legal experience. One, one of my board members actually launched two companies himself in the diagnostics industry, one in humans, and then later one in veterinary medicine. So he knew the industry and he also knew what it takes to launch a company. Another one of my board members has also launched two start up companies.

[00:36:59] >> James Jacobson: So how do you think your approach is going to, I mean, it is a different approach and that’s, again, one of the things that struck me when I started looking at your company, it is such a different approach. Why do you think it is more likely to be successful?

[00:37:14] >> Tammie Wahaus: I think if you look at uh successful public companies, for example, and you look at the board of directors of a successful public company, they don’t all look the same. And I worked a lot with, you know, Fortune 500, Fortune 100 companies and they, they would evolve their boards over time based on where their company was, issues that they were dealing with, and where their company was going. And so you add, you shrink, you change so that you have the best experts in the areas where you’re going to be delving into.

So I really patterned it after what did it take for public companies to be successful.

[00:37:57] >> James Jacobson: So like, who did you model when you were putting ELIAS together?

[00:38:00] >> Tammie Wahaus: Uh, so I had a number of clients and a number of companies that I was involved in, but you know, if you look at General Electric, if you look at local companies like Garmin, INNERGY, they all, you know, really focus on what is the expertise we need on the board so that we get the best thinking.

Now what we did, because we are in life sciences, we also then supplemented, right, with a scientific advisory board, which is almost solely veterinarians. So when we want to talk about, how are we going to design this clinical trial, or how do we feel about the next cancer type as a target, that’s the group we bring together, the veterinarians, oncologists, who have been in the field, some of which are still in the field, right?

But when we’re talking about raising money and making infrastructure investment, and all of that, we go to the board of managers.

[00:38:57] >> James Jacobson: It’s such a fascinating approach, you know, since, we’re sort of turning this slightly into a business story, because I think that this part of what is unique in your approach to this. What do you see as the exit for ELIAS?

[00:39:08] >> Tammie Wahaus: So I think there are a few potential possibilities, and I think it’s important as companies who are moving into new technologies and new manufacturing processes like we are, that you build the company, build the product, build the market. And then you will have multiple shots on goal, right, for exit. So an exit opportunity for us would be to, potentially to one of the animal health pharma companies.

One exit could be a public offering and we become a public company. One exit could be a private company making a significant investment in us and taking control. So really trying to make sure, you know, that we stay true to the mantra: Does your product work, can you make it, and does anybody want it? And if we can answer those three questions, we should have, you know, opportunities for exit. They’ll come at various times, right?

Pharma companies tend to acquire technologies right around licensure. Private equity may do it sooner than that. Going public might need to be after that. So trying to keep all of the opportunities in the forefront so that we’re prepared at any point in time, because the one thing that we can’t control is what’s happening in the marketplace, what’s happening in the economy. And what’s most important to us is to get this product to the patients who need it.

[00:40:37] >> James Jacobson: Well, it’s a fascinating approach, both in terms of the science and how you have created an entity to bring it to market. Tammie, thank you so much for being with us today. I really appreciate it.

[00:40:49] >> Tammie Wahaus: Thank you. It’s a pleasure visiting with you.

[00:40:53] >> James Jacobson: Immunotherapy is definitely cutting edge and holds a lot of promise for treating cancer, both in dogs and in people. And that’s why we like to talk about it here on Dog Cancer Answers, because there are so many different approaches and dogs are such awfully good models.

Again, words we’ve heard many times before, a Harvard study said years ago, if we can do it in dogs, we can do it in people. And this approach seems really worth following, and we will be letting you know about the results when they come out later in 2022.

I want to thank you for watching, or listening, today, ’cause we’re also on YouTube. If you’re listening to it in audio, you can watch it on YouTube or listen to it in your favorite podcast player. We have a whole bunch of back episodes of Dog Cancer Answers, which you can find on our website at dogcanceranswers.com.

I’m James Jacobson. From all of us here at Dog Podcast Network, I want to wish you and your dog a very warm Aloha.

[00:41:58] >> Announcer: Thank you for listening to Dog Cancer Answers. If you’d like to connect, please visit our website at dogcanceranswers.com, or call our Listener Line at (808) 868-3200. And here’s a friendly reminder that you probably already know: this podcast is provided for informational and educational purposes only.

It’s not meant to take the place of the advice you receive from your dog’s veterinarian. Only veterinarians who examine your dog can give you veterinary advice or diagnose your dog’s medical condition. Your reliance on the information you hear on this podcast is solely at your own risk. If your dog has a specific health problem, contact your veterinarian.

Also, please keep in mind that veterinary information can change rapidly, therefore, some information may be out of date. Dog Cancer Answers is a presentation of Maui Media in association with Dog Podcast Network.

Hosted By

SUBSCRIBE ON YOUR FAVORITE PLATFORM

Topics

Editor's Picks

CATEGORY