EPISODE 227 | RELEASED September 4, 2023

Apoptosis Explained Simply and Why It Matters in Dog Cancer | Amanda Kin, M.S.

Biology professor Amanda Kin explains apoptosis as if it’s an episode of Law & Order: SVU. Is the cell dying by accident, suicide, or murder?

SHOW NOTES

Enter the fascinating world of cell death, where nosy neighbors can tell each other to “die, already” … and cells can wake up one day and realize there’s something very, very wrong.

Also learn how cancer manipulates the conscientious cells to make them blissfully unaware of their own wrongdoing … or holds them hostage while they desperately, desperately try to do the right thing and kill themselves for the good of everyone.

It’s a glimpse into a world where cells seem sentient, and one could almost start to believe in miracles.

Links Mentioned in Today’s Show:

Article on apoptosis: https://www.dogcancer.com/articles/stats-and-facts/apoptosis/

Curcumin: https://www.dogcancer.com/articles/supplements/curcumin-for-dogs/

Apocaps supplement: https://Apocaps.com

[00:00:00] >> Amanda Kin: One of my favorite assignments that I would give my students is that there are three cell deaths: accidental, suicide and murder.

[00:00:11] >> Announcer: Welcome to Dog Cancer Answers, where we help you help your dog with cancer.

[00:00:17] >> Molly Jacobson: Hello friend, I’m Molly Jacobson. Today on Dog Cancer Answers, we’re looking at something that has a role in both causing cancer and treating cancer, apoptosis. Apoptosis is a good thing that we need to happen, but cancer cells cheat. To explain how all of this works, we’re joined by Amanda Kin. Amanda has been a biology professor for over 16 years and passionate about science data and, of course, dogs. Amanda, thank you so much for joining us today.

[00:00:49] >> Amanda Kin: My pleasure.

[00:00:50] >> Molly Jacobson: We are going to talk about apoptosis, which I like to call the thing none of us remember from high school biology.

[00:00:59] >> Amanda Kin: Yes, absolutely.

[00:01:01] >> Molly Jacobson: And you teach biology. So you are the person to be here with us today. Tell us a little bit about yourself.

[00:01:09] >> Amanda Kin: So I am the daughter of a veterinarian. So that was kind of how science and animals became one of my first loves. But my mother was a concert pianist. So got a giant dose of the creative as well, went to Ohio State and studied animal studies, thinking that I would go to vet school, got very interested in research and kind of took a left turn and originally went into a doctoral program and did not realize that funding, research funding is a thing when I started my program. And so, uh, funding.

[00:01:47] >> Molly Jacobson: You can’t just study science.

[00:01:49] >> Amanda Kin: You can’t, it’s just not an unlimited pile of money for you to study whatever you want. Uh, so, um, ended up my major professor lost funding halfway through my project and they kind of said, look, I think we can get you out of here with a master’s degree. So that’s how I ended up with my master’s degree, which is actually in reproductive physiology.

And they say, and now I’m a true believer, that almost more important than your degree title is the first job that you get when you leave college. And I, to make ends meet, was part time teaching at a local community college in Columbus, Ohio. And that became what my experience was in, so I landed my next job, and my next job, and my next job, and it was always teaching biology. And so now I am down in Alabama. I’m teaching at a community college down here.

[00:02:45] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s wonderful. And you’re a dean.

[00:02:48] >> Amanda Kin: Yes. Uh, so, went, went through the ranks of administration. I do, I do still teach biology when they need somebody to stand in like somebody, my favorite is when somebody goes on maternity leave and I get to take some of their classes that are, you know, professors not feeling well, I’ll go fill in on their classes, but now I do a lot of data. So, because of my background in research science, I run a lot of the data reporting and statistics and data modeling for the college.

[00:03:21] >> Molly Jacobson: So that’s a really, really interesting background. And what I love about your background is that you’ve got all of the science and you’ve got the heart and then you’ve got all of this really solid experience of helping people understand.

[00:03:36] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:03:36] >> Molly Jacobson: Through teaching, but also administration is very much a job where you need to understand people and you need to understand how to bring them together. And that’s a lot of what we do here at Dog Cancer Answers, is help people connect to their veterinarians and to the information that they most need at a really critical time in their life. So just, I’m so glad that you’re here with us.

[00:03:56] >> Amanda Kin: Absolutely. Managing an illness like that in your dog is managing a giant project with many, many moving parts and the need to understand a lot of things that are probably outside your comfort zone.

[00:04:08] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. So now we’re going to talk about apoptosis, which is happening all the time.

[00:04:14] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:04:14] >> Molly Jacobson: But we don’t even know what it is. And it’s got a weird name, and it’s yet kind of at the heart of cancer.

[00:04:22] >> Amanda Kin: It is.

[00:04:23] >> Molly Jacobson: So why don’t you tell us about what is apoptosis?

[00:04:27] >> Amanda Kin: Sure. So apoptosis, in a nutshell is a programmed cell death, which seems like a very odd thing. Why would a cell contain a program that tells it to die? And there are a lot of good reasons that we don’t think about why cells would need to do that. And one of the most prominent, easy to understand examples is during embryonic development, we all have webbed fingers and toes. And there is extra skin running in between.

[00:05:01] >> Molly Jacobson: When we’re in the womb.

[00:05:02] >> Amanda Kin: Yep. And everybody looks like Aquaman, and you have your webbed fingers and toes, and so through apoptosis and that programmed cell death, that tissue is carefully taken away so that what remains when you’re born are your healthy fingers and toes.

[00:05:20] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So that’s a really great illustration. On a daily basis, though, what’s apoptosis being used for in the body?

[00:05:30] >> Amanda Kin: Sure. On a daily basis, we are turning over billions of cells. Your body has to both make new cells, and take away old cells. So anytime that there is a detectable defect in a cell, it can undergo apoptosis. And I’m laughing here. And I was reading our definition on the website about apoptosis versus apoptosis and the different ways that you can pronounce that. And so I’ll stumble as I switch back and forth between the two of them.

[00:06:06] >> Molly Jacobson: Well, how do you prefer to pronounce it? Because I think, you know, it’s a matter of preference or maybe even region.

[00:06:12] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah. It’s funny. At every major professor I ever had, I always said a-pop, we got the second P in there. And it’s funny because I switched, if I’m just saying the word apoptosis, sometimes I will drop the P, but if I have to do any derivation of the word, I find that I add the P back in. So if I say apoptotic or apoptogen, then I, I find that P sneaks right back in .

[00:06:37] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, that’s interesting.

[00:06:38] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:06:39] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. Well, the P maybe needs to be deleted.

[00:06:44] >> Amanda Kin: Agree.

[00:06:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Like a cell that needs to die.

[00:06:47] >> Amanda Kin: That is a very good analogy to what they should do to that word.

[00:06:55] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay, so every day we need to make new cells and we have to get rid of old cells.

[00:07:01] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:07:02] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah, that should not be here any longer because they are, you said, deranged or have a defect?

[00:07:08] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah, all cells kind of live in, what I try to explain is, like this slurry of there are pro survival signals and there are pro death signals. So pro survival signals are going to be, you know, we need more liver cells. So the liver is able to make more cells and regenerate itself. And so we would have a lot of pro survival signals in the environment of the liver. There are pro death cells such as there are too many of you, your DNA is defective. You are expressing a gene too much, you are expressing a gene not enough.

These are signals that could be categorized as pro death because there is something defective going on in that cell and then it would undergo apoptosis in order to eliminate itself from the population and from potentially causing any harm.

[00:08:08] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s fascinating. I find this so fascinating that all of our cells are sort of these little, I’m a writer. So I’m being creative here. Acknowledge like there’s not brains and cells, but there is intelligence in the way that all of these things work somehow and that they’re checking themselves and saying, am I okay? And then the outside environment is also saying, are you okay?

[00:08:32] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:08:32] >> Molly Jacobson: And if the answer is no and let someone else do the work, that’s good. Am I being too, um, flights of fancy?

[00:08:38] >> Amanda Kin: No, no, no, no, no. I am right there with you. I always say, if you have never thought about what a miracle is, or what’s a modern day miracle, the cell, the development of a cell, the functioning of a cell, embryonic development, all, I mean, the amount of coordination and capability contained in such a tiny, tiny amount of space is nearly unfathomable.

Like, you’re absolutely right. It is monitoring what’s going on the inside. It’s monitoring itself. It’s monitoring its neighbors. It’s monitoring all of the fluid around it. And then there are these larger mechanisms that are monitoring at tissue levels, at organ levels, and they’re all coordinated. They’re all coordinated. And it is, it really is amazing. All of the tiny little things that we take for granted that are happening on such an elegant level.

[00:09:37] >> Molly Jacobson: Yeah. In every cell, billions of cells.

[00:09:40] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:09:41] >> Molly Jacobson: How many cells undergo apoptosis? How many cells sacrifice themselves for the good of the body, on a daily basis, in a dog or in a human if whatever number you have off the top of your head?

[00:09:53] >> Amanda Kin: Oh, gosh, I would say millions, hundreds of millions every day are going to undergo apoptosis, some for reasons like cancer. Cancer is a great one. If, if there is a destructive mechanism that would lead the cell to begin to rapidly divide, they should automatically undergo apoptosis. And then there are some mechanisms in your body that use apoptosis as a normal part of their functioning.

The immune system, for example, has to evaluate. T-cells, which are your cells that protect you from viruses and foreign invaders. But when they’re born, they are not born with any kind of like, Hey, by the way, you should only attack foreign invaders. They are built to attack everything. So there will be T-cells that attack your own tissue.

And so by a natural process, those cells have to be deleted. And of course we can all run that thought out if that mechanism fails and those cells are not deleted and they’re allowed out into your system and attack you, that’s, that’s one of the genesis is for autoimmune disease.

[00:11:05] >> Molly Jacobson: Oh, so that’s why some of these therapies that are used in cancer are also used in autoimmune diseases.

[00:11:17] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah. Particularly if it is about increasing apoptosis.

[00:11:22] >> Molly Jacobson: Apoptosis.

[00:11:23] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:11:23] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. I just sort of jumped the gun there, but that’s so fascinating.

[00:11:27] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:11:28] >> Molly Jacobson: I wanted to talk about things that induce apoptosis a little bit later on, but that is fascinating. So the T-cells are born without a memory of what to do and so they just kind of go crazy until they learn what to do or are deleted. Is that right?

[00:11:47] >> Amanda Kin: It’s actually fascinating. The way that T-cells develop, to get totally off topic, um, is that they have this set of genes that they can recombine in practically an infinite amount of combinations. Like it is, you know, to the nth degree, they can just recombine and recombine. And every time they recombine, that’s one cell.

And so when I teach this in class, I always say something like this cell recognizes triangle. This cell recognizes square. This cell recognizes octagon. And so we have all these cells that have a shape. And then they’re tested. They’re tested with a self-protein. So, we walk by and we say, triangle, do you recognize this?

No, I don’t recognize that. Square, do you recognize it? No, I don’t recognize that. Octagon, do you recognize it? I do recognize it. I’d like to attack that self-protein. Er, you have to be eliminated.

[00:12:38] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s going on all the time to test our T-cells. Our body is testing our T-cells like that.

[00:12:45] >> Amanda Kin: It’s happening the most frequently from three, like from the time you’re born, it gets really ramped up around three years old. It goes on. It does start to decline as we age, but it is a process that is happening in most adults all the time.

[00:13:02] >> Molly Jacobson: That is crazy.

[00:13:04] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:13:04] >> Molly Jacobson: So our T-cells are born and then they are supposed to recognize our body cells and if they don’t, they are deleted through apoptosis.

[00:13:14] >> Amanda Kin: Other way around, they’re not supposed to recognize your body cells.

[00:13:18] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. They’re not supposed to recognize it. Because if they recognize something, they attack it.

[00:13:23] >> Amanda Kin: Correct. So.

[00:13:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow.

[00:13:25] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah, we are just pumping out these T-cells under a random recombination of genetic material. There’s no rhyme or reason to it. So, inevitably, you are going to, in that random recombination, you are going to generate receptors that recognize self-proteins, and we have to find them and eliminate them before we allow them out to the general circulation.

[00:13:44] >> Molly Jacobson: So even the way you’re talking about this, it’s like there’s a, a quality control system in the body and there’s like people in the body who are thinking and making decisions and enforcing rules and they have clipboards and checklists and they say, Do we have enough? Do we need to make more?

[00:14:01] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:14:01] >> Molly Jacobson: Do we have too many?

[00:14:02] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:14:02] >> Molly Jacobson: Is this working?

[00:14:03] >> Amanda Kin: That’s absolutely how I explain it.

[00:14:05] >> Molly Jacobson: Little engineers..

[00:14:06] >> Amanda Kin: Yes. That is absolutely how I explain it when I’m teaching. I’m like, they talk to each other. They have a secret handshake. They say yes. They say no. They say good. They say bad.

[00:14:14] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s incredible. There’s a whole world going on in our body. There’s a whole world of activity going on.

[00:14:21] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:14:21] >> Molly Jacobson: And in the dog’s body.

[00:14:23] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:14:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Right.

[00:14:24] >> Amanda Kin: Dogs are so similar.

[00:14:26] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. Is this the only way thaT-cells die, through apoptosis?

[00:14:30] >> Amanda Kin: No. Actually, one of my favorite assignments that I would give my students is that there are three cell deaths: accidental, suicide, and murder.

[00:14:44] >> Molly Jacobson: Ooh, it sounds like manslaughter.

[00:14:47] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah, exactly. First degree, second degree.

[00:14:50] >> Molly Jacobson: Second degree.

[00:14:51] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:14:52] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow. Okay.

[00:14:53] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:14:54] >> Molly Jacobson: All right.

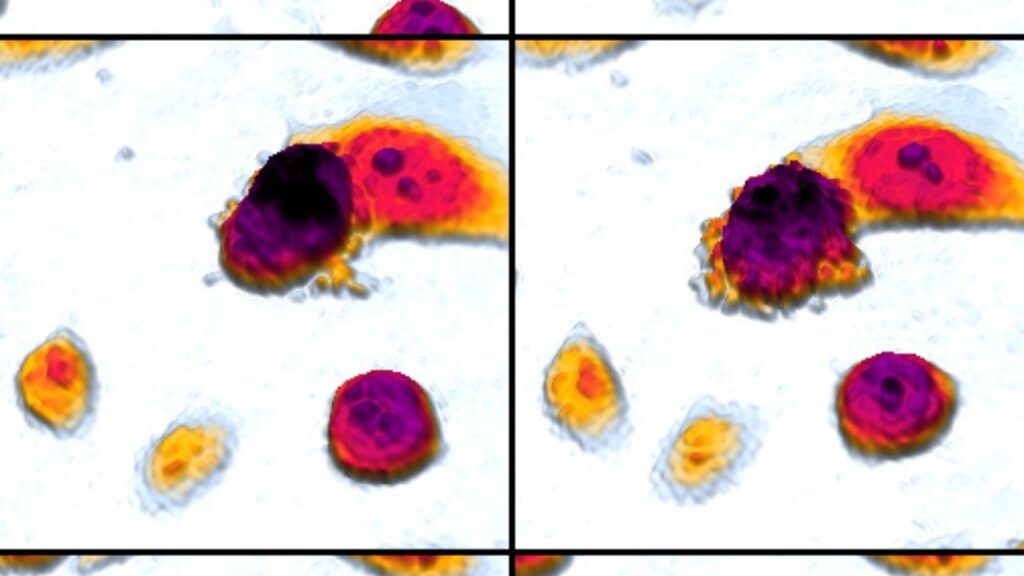

[00:14:54] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah. So we would do like this little SVU assignment and I would let them look at cells under a slide and then I would give them some details and I would say, you know, you’re the detective. Did the cell die? If it’s an accidental death, was it a suicide or was it murder?

And actually, suicide and murder are both forms of apoptosis and accidental death is necrosis. So if it’s beyond the cell’s control, that’s accidental. It didn’t want to die. It had no intent on dying, but something externally happened to it. and killed it, we say, you know, by accident. So that’s a necrotic death. And then suicide and murder would both be forms of apoptosis. The difference being if something went wrong internally, if the DNA was deficient, that would be suicide. There’s

also a mechanism whereby other cells can say, there’s something wrong with you. You need to die. And so they get an external sign and that’s murder, but we see a lot of when we break it down the genes and the proteins and all the processes that happen, it’s similar, but one is started by internal mechanisms within the cell, that’s the suicide and one is started by external mechanisms by surrounding cells, and that’s the murder.

[00:16:18] >> Molly Jacobson: So when it’s a murder, when other cells tell a cell to die, is it the same genes, the apoptosis genes that are turned on by other cells? Are they able to do that? Or how does that work? How do they murder?

[00:16:31] >> Amanda Kin: So they send essentially, they will secrete a protein. It’s picked up by a receptor on the defective cell. They bring it in like they’re getting a piece of mail. They read their mail, Hey, something really wrong with you.

[00:16:46] >> Molly Jacobson: Time to go.

[00:16:47] >> Amanda Kin: It’s your time. And so then they would be.

[00:16:50] >> Molly Jacobson: My god.

[00:16:51] >> Amanda Kin: They would begin to enact their very similar mechanisms of apoptosis as if they were like, I’m not feeling well, there’s something very wrong with me. I don’t think I can recover from this. It’s time to go. And then once that signal is released, we see very similar mechanisms happening.

[00:17:09] >> Molly Jacobson: Both of which are apoptosis.

[00:17:11] >> Amanda Kin: Yes, but they both qualify as apoptosis. And just as an aside, histologically, what we normally see is that apoptotic, see?, as soon as I derive the word, I get the P back. Apoptotic cells tend to blow up and necrotic cells that die by disease tend to shrink in on themselves. So that’s why I like to do a little histology slide because sometimes you can just look at a set of cells under the microscope and you can already get a pretty good idea of whether it was accident, suicide, or murder.

[00:17:44] >> Molly Jacobson: What’s the difference under the microscope between suicide and murder?

[00:17:49] >> Amanda Kin: So suicide and murder would be, with a regular microscope that we have in a biology lab, you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

[00:17:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:17:57] >> Amanda Kin: The outcome would look the same.

[00:17:59] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. All right. Because it’s such a similar process of apoptosis.

Let’s pause here to hear a word from our sponsors and we’ll be back with Amanda Kin speaking more about apoptosis.

And we’re back with Amanda Kin. Okay. So what does all of this have to do with cancer cells?

[00:18:21] >> Amanda Kin: Absolutely. So one of the great discoveries about cancer had to do with a cancer cell, their ability to avoid suicide and murder. So, when a cell has a defective DNA, let’s say that causes it to multiply rapidly, which is a hallmark of a cancer cell, we’re getting too many cells rapidly dividing in the same area and they’re going to end up a tumor.

There are so many mechanisms in place to prevent that from happening. Both, they should have an internal saying this doesn’t feel right and other cells around them will be frantically sending them mail saying something’s wrong with you.

[00:19:04] >> Molly Jacobson: You’re going off the rails.

[00:19:05] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah. The homeowner’s association is coming after you.

[00:19:09] >> Molly Jacobson: You’re living too long.

[00:19:09] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:19:10] >> Molly Jacobson: Cut your lawn.

[00:19:14] >> Amanda Kin: So there should be all these signals, but what we see in cancer cells is that they have repressors on those genes. So they have a way of getting into the DNA and essentially locking up the gene that would allow them to undergo apoptosis. And then we also see the overexpression.

There are molecules out there, proteins out there that can inhibit apoptosis and we see that they’re expressing too much of this protein and they’re not able to access the genes that would allow them to undergo apoptosis. So even if they know something’s wrong, they’ve been cut away from their machinery and they can’t do anything about it.

[00:19:56] >> Molly Jacobson: That’s incredible. So the cancer cell might actually know that there’s something wrong with it and be trying, but unable to start that process.

[00:20:06] >> Amanda Kin: Correct.

[00:20:06] >> Molly Jacobson: Because it’s been locked away.

[00:20:08] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:20:09] >> Molly Jacobson: And then other times, if I heard you correctly, that other times, It isn’t aware that there’s something wrong because those signals are not letting that mail come in.

[00:20:20] >> Amanda Kin: Yes. So if we see the overexpression of an anti apoptotic protein, the cell can’t tell that there’s something wrong because they, they’re getting a pro survival signal. So, and that’s that Bcl-2 is a pro survival signal. So we talked about that balance between pro survival and pro death. So it doesn’t matter how many pro death signals are coming in from your neighbors, you’re floating in a pool of pro survival signals.

And then there may be other cases when the gene, and that’s that P53 that we always see referenced, that’s the apoptosis, one of the main apoptosis genes. I know something’s wrong, I’m getting all this mail, I keep trying to break the glass so I can hit the button, and they’ve encased it in cement and I can’t get to it.

[00:21:06] >> Molly Jacobson: Poor little cell.

[00:21:07] >> Amanda Kin: I know. It really, we talk about wanting to assign, you know, sentience to these cells and when you introduce the mechanisms of a cancer cell, it makes me want to do it even more. Like they’re actively out there, like mission impossible-ing through our system, trying to avoid and go undetected.

And then you can make copies of yourself after that. So let’s shut down apoptosis and quickly let’s start cloning ourselves. Let’s start making more copies of more cells that have the exact same defect. It’s the beginning of a tumor.

[00:21:42] >> Molly Jacobson: Wow. Okay, so there’s this concept that I find very useful called hallmarks of cancer. That every cell that is a cancer cell has things wrong with it that are the same so that every, no matter where the cell is in the body or what type of cell it is, it’s a squamous cell carcinoma, or it is a sarcoma, no matter where it’s located or what type of cell is the problem cell, it’s sharing these same characteristics.

And the reason I think it’s interesting that all cancer cells share characteristics is because that points us towards all cancer cells do these things or have these features, therefore, we can find treatments that target those features and tie it back to how to prevent, possibly, maybe someday, and treat cancer.

So this is why some things help all cancer types, not just one or two. Like we can look at it sort of from a holistic perspective this way. So, apoptosis, I assume, is a hallmark of cancer?

[00:22:49] >> Amanda Kin: Absolutely.

[00:22:51] >> Molly Jacobson: A lack of apoptosis.

[00:22:52] >> Amanda Kin: Yes. Yeah. The inability to undergo those normal reasons you would undergo apoptosis is definitely a hallmark of cancer.

[00:22:59] >> Molly Jacobson: And as you pointed out before, also a hallmark of autoimmune diseases.

[00:23:04] >> Amanda Kin: It can be. I wouldn’t say it’s a hallmark because autoimmune can start for a lot of reasons.

[00:23:10] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:23:10] >> Amanda Kin: That is just one of the reasons that they can start.

[00:23:13] >> Molly Jacobson: One of the reasons.

[00:23:15] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:23:15] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So, how is this information useful to researchers and clinicians who are treating cancer in humans and also in animals and specifically in dogs?

[00:23:30] >> Amanda Kin: So, being a hallmark is great. There are, we are talking in, in very broad generalities, but this gets so complex and so complicated on a genetic level. And different types of cancers access different proteins, and that can be a hallmark for that brand.

[00:23:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:23:55] >> Amanda Kin: And I think a huge part of treatment is getting that correct identification, right? Knowing exactly what kind of cancer that you’re dealing with as specifically as you can.

So when we know more about apoptosis, and we know the specific genes that might get turned on and off for carcinoma, for cancers of the blood, for any of these, you know, ovarian cancers, for any specific cancers. If they have hallmark genes that that brand of cancer is using to avoid apoptosis, that gives us such a great piece of identifying information that can inform researchers and clinicians in treatment plans.

[00:24:43] >> Molly Jacobson: Right, it’s like if you were going to, if you were going to be an auto mechanic and you’re going to work on lots of different cars. You’re going to have a lot of parts in stock and some will be universal and others not. There might be just a very specific bolt that you need to use on this very specific type of car.

[00:25:00] >> Amanda Kin: Yes.

[00:25:01] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. Excellent. What are some of those treatments that you have in mind? Are there like foods, are there supplements, are there specific medications?

[00:25:10] >> Amanda Kin: So, I do know out there that there’s a huge amount of work going on around natural occurring substances that can be called, uh, I’m going to put that P back in, apoptogens. And, I’m having a teacher moment. I like to point out to people when -gen is in the bit of a word, if you see -gen, it’s genesis, it’s making it happen, making whatever’s in front of it happen. So an apoptogen is something that can generate or create the genesis of apoptosis. I love breaking down words.

The biggest one that we see out there that is totally naturally occurring are the flavonoids. So the most popular flavonoid that we see is probably in turmeric. It’s got curcumin in it, and we see that that, as per usual, Eastern medicine has been using a lot of these compounds much longer than Western medicine. And one of the major things that we see with flavonoids, with that family, is that they can increase the amount of apoptosis happening in the body.

And so we see many health effects coming out of, of turmeric, but that’s one of them that specifically references apoptosis.

[00:26:26] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay.

[00:26:27] >> Amanda Kin: Another one are the alkaloids. Alkaloids are also shown to increase apoptosis. I read a study not too long ago, great effects in ovarian cancer actually, at increasing the apoptosis that was happening when they tested it specifically in vitro, which means inside of a lab, inside of a dish, on different ovarian cancer cell lines. They saw that the alkaloids were doing great there.

[00:26:55] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. So what’s an example of an alkaloid that induces apoptosis?

[00:27:00] >> Amanda Kin: So one of the alkaloids that’s studied pretty extensively is actually called berberine, and it is a compound that we get out of plants and we see it being researched. I’ve read a few articles about it being researched in ovarian cancer in the lab as something that helps to induce apoptosis in those ovarian cancer cell lines.

[00:27:24] >> Molly Jacobson: Wonderful.

[00:27:26] >> Amanda Kin: The last major category I can think of are hydrocarbons. And I remember that one is, uh, citrus. Citrus has a lot of the hydrocarbons that we see that are effective. And I’ve seen those ones probably studied the least. The most studies that I’ve seen are in the flavonoids with the tumeric, but the hydrocarbons I’m seeing more and more and more of, because again, I mean, citrus peel’s so readily accessible.

[00:27:54] >> Molly Jacobson: And so that’s where those hydrocarbons are concentrated is in the citrus peel?

[00:28:00] >> Amanda Kin: Correct. And it’s like limonene. It’s like L I M O N E N E. Limonene I think is the compound that they’re getting out of the citrus peels. And, and testing it and.

[00:28:12] >> Molly Jacobson: And that’s what smells so good.

[00:28:15] >> Amanda Kin: Yes. Yeah. And for, um, as an aside for anybody listening, when these studies are conducted in labs, they’re not taking a lemon peel and doing an experiment on it. That they have all this great machinery that can separate anything into its individual molecules that are then purified and identified through so many different scientific means.

So as we discuss these and we’re talking about how great it is that they’re readily accessible, we certainly don’t advocate that you run out and grab any citrus peels or a jar of turmeric and begin your own treatment.

[00:29:01] >> Molly Jacobson: Right. Yeah. It’s in the food, but it’s not necessarily the food, as a whole, that they’re studying.

[00:29:08] >> Amanda Kin: Correct.

[00:29:08] >> Molly Jacobson: So yeah, that’s a complex conversation right about. Is it everything working together that’s been helpful? Is it just the individual thing? And that’s a real discussion even amongst holistic practitioners.

[00:29:21] >> Amanda Kin: Absolutely.

[00:29:22] >> Molly Jacobson: You know, that should you use an extract that, you know, has been standardized and is pure and it’s doing exactly what you know to do from the lab works, or should you be using a whole food where you perhaps get all these synergistic benefits from the other compounds that might be present? But then how do you standardize that and know you’re getting the right dose. So these are not straightforward questions that we can just say, this is what you should do.

[00:29:48] >> Amanda Kin: Yeah.

[00:29:48] >> Molly Jacobson: Certainly not giving your dog a lot of citrus peels to chew. That’s not the answer to cancer.

[00:29:53] >> Amanda Kin: No.

[00:29:54] >> Molly Jacobson: Are there any foods that you think are really packed with apoptogens that might be useful to, I don’t want anybody to think I’m only going to feed this food, but like, might be useful as a, an addition to the diet, a topper to the diet and inclusion in the diet for dogs with cancer? I know you’re not a veterinarian and you’re not a nutritionist. So it’s just things for people to take to their own veterinarian as an idea.

[00:30:20] >> Amanda Kin: I can’t think of just like a food. Definitely supplements would be available. There are Apocaps, which are specifically targeted supplements to increase apoptosis. So that’s definitely something. Looking into supplements if you’re looking to take a conversation to your vet. I can’t really, you know, I can’t say like broccoli or, you know, which is my favorite superfood. I can’t think of off the top of my head, like just one food where I’d be like, yeah, that’s, that’s the apoptosis food. But I would go more of the supplement route.

[00:30:56] >> Molly Jacobson: Okay. All right. Great. Thank you so much, Amanda Kin, teacher extraordinaire. It’s been so fun having you on. I hope you’ll come back and teach us more about biology and really, um, you’ve done such a wonderful job of bringing this to life and really helping us understand apoptosis in a new way. Thank you.

[00:31:16] >> Amanda Kin: Thank you. It’s definitely my pleasure. I so rarely get to talk about these things anymore.

[00:31:22] >> Molly Jacobson: Well, you can come back anytime.

And thank you friend for listening. I hope that this discussion about apoptosis was as enlightening and fun, unexpectedly fun, as it was for me, and that you learned a lot. We will be having Amanda Kin back and I encourage you to go to DogCancer.com. You can visit the links in the show notes and read all sorts of articles, not just about apoptosis, but other treatments and supplements and foods that help to boost apoptosis when needed and get through that blockade that cancer cells have set up.

Please join us on our socials and follow us wherever you get your podcasts. I’m Molly Jacobson, and from all of us here at Dog Podcast Network, I’m wishing you and your dog a warm, Aloha.

[00:32:19] >> Announcer: Thank you for listening to Dog Cancer Answers. If you’d like to connect, please visit our website at DogCancer.com or call our listener line at (808) 868-3200. And here’s a friendly reminder that you probably already know, this podcast is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It’s not meant to take the place of the advice you receive from your dog’s veterinarian.

Only veterinarians who examine your dog can give you veterinary advice or diagnose your dog’s medical condition. Your reliance on the information you hear on this podcast is solely at your own risk. If your dog has a specific health problem, contact your veterinarian. Also, please keep in mind that veterinary information can change rapidly, therefore, some information may be out of date.

Dog Cancer Answers is a presentation of Maui Media in association with Dog Podcast Network.

Hosted By

SUBSCRIBE ON YOUR FAVORITE PLATFORM

Topics

Editor's Picks

CATEGORY