EPISODE 166 | RELEASED May 9, 2022

Dog Cancer Vocab: Mitotic Index | Dr. Brooke Britton

Oncologist Brooke Britton breaks down what mitotic index means for your dog with cancer, and when having this number can be helpful.

SHOW NOTES

Mitotic index is one of the many complicated-sounding medical terms that may be thrown at you after your dog is diagnosed with cancer. At its most basic, mitotic index is the count of how many cells in your dog’s tumor are actively dividing, or reproducing. But what does this mean for you and your dog? Dr. Britton breaks down how mitotic index can help determine the prognosis for your dog, as well as which cancers it is most significant for. The aggressive potential of some cancers is closely linked to the mitotic index, while others can still be treated successfully even if the mitotic index is sky-high.

Listen in to learn about the nuances of mitotic index, how to get it for your dog’s tumor, and when it is most important to know this number before you make treatment decisions.

Links Mentioned in Today’s Show:

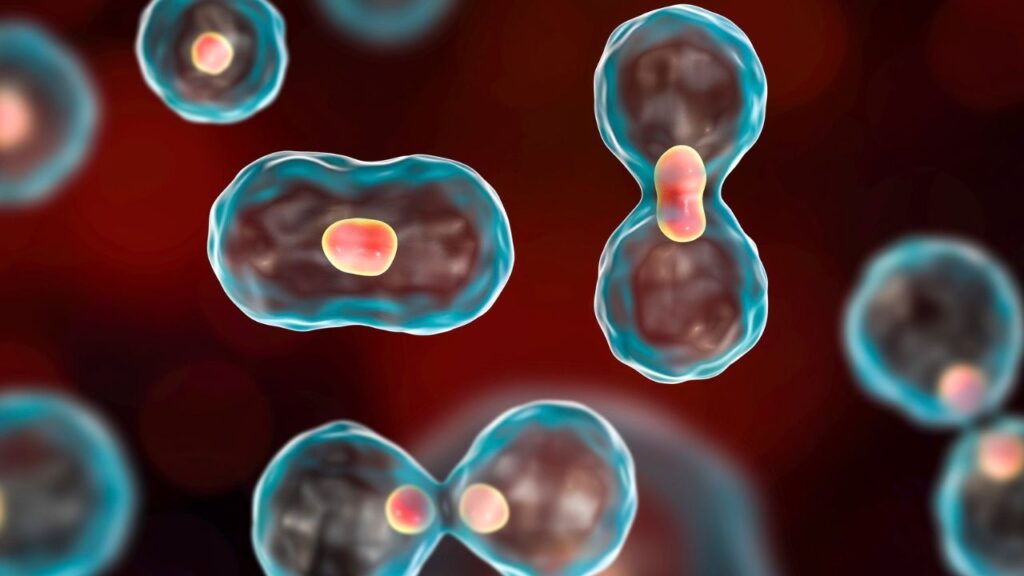

National Human Genome Research Institute article on mitosis with images and video

[00:00:00] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Mitotic index is just one factor amongst many that goes into determining tumor behavior, that goes into clinical decision-making. So I have had tumors with higher mitotic indices where I’m more concerned that this is going to be aggressive and that led me to treat perhaps more aggressively than if it had been lower.

[00:00:24] >> Announcer: Welcome to Dog Cancer Answers, where we help you help your dog with cancer. Here’s your host, James Jacobson.

[00:00:32] >> James Jacobson: Hello friend and welcome. Today, we’re going to unravel one of those crazy vocabulary words that we hear about when it comes to dog cancer: mitotic index. What is it, and why is it important? To help us figure this out, we are joined by veterinary oncologist Dr. Brooke Britton who joins us from New York. Dr. Britton, thank you so much for being with us.

[00:00:57] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Thank you for having me.

[00:00:58] >> James Jacobson: So let’s talk mitotic index. What does it mean for dogs?

[00:01:05] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yes. So mitotic index is an indication of the ratio of cells in a cancer sample that are actively dividing, or in mitosis, proportional to the rest of the cells in the sample.

And so when a pathologist gives a mitotic index – that’s typically when you’ll have that number reported – they’re counting, physically counting, the number of dividing cells in the sample that they’re looking at over typically 10 random, what we call high powered fields under the microscope. And then they come up with a number and putatively the higher that number is, the more cells are dividing, and in many cases indicates a more aggressive, rapidly growing tumor. But there are some exceptions to that rule.

[00:01:55] >> James Jacobson: Okay. We’ll get into that in a minute, but we have so many smart listeners who really want to kind of understand all the nuances of this. So they’re taking a sample through like a biopsy or something like that, putting it under the microscope. And then when you say 10 different random pieces, can you elaborate on that?

[00:02:13] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Sure. So when we have a tumor and we want to get more information, let’s say a grade of a tumor, just like in human medicine, or if we want to understand different parts of the architecture of the tumor, how aggressive it is, and sometimes to get a diagnosis, if we don’t know what we’re dealing with, we take a biopsy.

So we’ll take a piece of the tumor, and sometimes that means taking a small piece with a tool, or sometimes it means removing the entire tumor in what we call an excisional biopsy. When that biopsy is taken, it’s put in a preservative, typically formalin, and sent to a laboratory. And usually what happens when it gets to the laboratory is, after it’s fixed and the preservative kind of fully infiltrates that sample, then the sample is prepared for the pathologist to examine it. And how they do it is they slice the tumor, like a bread loaf, and they slice it into very, very thin sections.

They’ll put that sample on a microscope slide and then the pathologist will look at that tumor’s slice under a microscope and he will do, or she will do, a scan of the entire slide – and there are many, many slides that are typically prepared – get an overall sense of what that tumor looks like and if they can put a name to it, and then they’ll dial down on a very high power or large magnification so they get a really close up picture of the tumor, and then they’ll usually count over 10 random fields of sight.

So there’s a lever on the microscope that allows them to kind of move from section to section on the slide, and they’ll go through 10 random fields of sight, usually scanning up and then over and down sequentially and they’ll physically count the number of cells that look like they’re actively dividing. And they can tell what these cells are because they have a very characteristic appearance.

So you can actually see the genetic material or the chromosomes oftentimes bunched up in the middle of the cell or kind of pulling away almost like an accordion. And so when they see those cells with that characteristic appearance, they’ll count the number of cells per random field. And once they get to 10 they’ll count the total number that they have, and they’ll make a number. Let’s say I see 10 actively dividing cells over 10 random fields of sight, then the mitotic index would be 10.

[00:04:36] >> James Jacobson: Okay.

[00:04:37] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: There’s not always consistency in how pathologists report this. So some will say, I see 10 cells per high-powered field, and then the mitotic index would actually be a hundred, right, because you’re looking at 10 random fields. And so if on average they’re seeing 10 in one, over 10, they’re seeing a hundred.

[00:04:57] >> James Jacobson: Right.

[00:04:57] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: So there’s some confusion sometimes how pathologists report this, but it should be per 10. And that number is an indication of how many cells are growing at the time, or dividing, at the time that the tumor is looked at. So it’s, it’s a snapshot in time. And it’s also representative of that particular section.

You know, if you looked at a different section of the tumor, sometimes the cell count could be lower, sometimes it could be higher, and the idea is to try and get an average because the tumor itself is not totally equal in terms of the entire mass of the tumor, if that makes sense. So it’s an impression-

[00:05:37] >> James Jacobson: ‘Cause they’re taking different slices, at different levels of, I mean, if they’re doing either a punch needle or the tumor itself, they’re looking at different slices from the tumor.

[00:05:47] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: That’s exactly right. And to your point, with different types of biopsies, if you have a punch sample, which is a tiny little circle that they take out of a tumor with a little tool with teeth on it, or if you have a true cut sample, where you’re taking a bigger needle on an injector that injects the needle with force and kind of pulls back a sample, those are very small samples that we’re getting.

And then if you take a big tumor off, you know, the size of a softball, for example, you’ve got more tissue to work with. And so oftentimes the more tissue you have, the better impression you get of that tumor as a whole, you know, versus taking a tiny little area, you have an impression of that tiny little area. If you’ve got a big tumor and you’ve got multiple sections through that big tumor, gives you a better idea of the tumor as a whole.

[00:06:37] >> James Jacobson: So as the pathologist is doing this and trying to determine the mitotic index within different slivers, do they sometimes see a one layer has a much higher number than another layer?

[00:06:49] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yes.

[00:06:50] >> James Jacobson: And so it’s really an, all an average.

[00:06:52] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: That’s where it gets interesting. It’s an impression. So you have a better, more representative impression when you have a bigger swath* *of samples through a tumor, versus a really tiny piece in one little focused area you may not have as good of an impression. What I will say is that with bigger tumors, and the reason is, right, sometimes tumors are actively growing, maybe at the leading edge or the outside of the tumor, and the inside, as it gets bigger, has less oxygen.

Those cells are less active. Maybe they’re not growing or they’re in a resting state. Maybe they’re dying. So the tumors are what we call heterogeneous. You know, they’re not uniform all the way through. And so the pathologist will often, if he gets, or she gets, a drastically larger number for a mitotic index in one section and then a smaller number and there’s discordance there, sometimes they’ll go with the bigger number because they want to err on the side of not undergrading the tumor because the grade and that number sometimes can really help us in terms of directing treatment. And sometimes it’s actually what’s called prognostic, meaning that number alone can make a difference in the outcome of how a dog or a cat does with therapy.

[00:08:11] >> James Jacobson: Okay. Well, let’s talk about that as an oncologist.

So once you get the report back from the pathologist and they have assessed the number, do they express all this nuance to you, or do they just basically give you a number when it comes to the mitotic index?

[00:08:26] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Sometimes.

[00:08:27] >> James Jacobson: It depends who the pathologist is.

[00:08:30] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Exactly. It depends on who the pathologist is. And the really nice thing about working in this specialty is that we get to know our pathologists really, really well.

And so we often have either preferred labs that we send to, or a preferred pathologist. But even if it’s someone we don’t know-

[00:08:47] >> James Jacobson: Can you get Henry to do it instead of Anita? Yeah.

[00:08:50] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Sometimes we do that. And some pathologists actually sub-specialize in certain tumor types, like dermatopathology, skin pathology. So sometimes we will have those preferences and other times we don’t, or if we don’t know the pathologists, you know, again, the good thing is we can reach out to them and most pathologists are very amenable to working with us in terms of if the language is not quite clear or if we interpret it one way and we’re not sure exactly if that’s how they meant it, you know, we can reach out and discuss that with them.

Some pathologists give a very lengthy report and go into a deeper explanation. Others just sort of give you minimal information and you may need to reach out to them and ask for more. But mitotic index, in general, it should always be something on the report. Whether or not it’s prognostic for a specific tumor, it’s a good idea to have that number, to get an impression of how aggressive the tumor might be. But that’s one factor, as you know, it’s not something to hang your hat on for any particular tumor type.

[00:09:49] >> James Jacobson: Well, let’s take a break right here, Dr. Britton, and then when we come back more about the mitotic index. We’ll be right back.

Welcome back. We are speaking with Dr. Brooke Britton. How important is it to have that number? What do you do with that number?

[00:10:07] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: It depends on the tumor, is the honest answer. There are tumors where it is vital to know, such as mast cell tumor, particularly in dogs, because mitotic index is prognostic and it goes into how they grade those tumors.

So the pathologist should be giving the mitotic index. They will give a grade, but they should be giving one because there are cutoffs. And if we’re close to that cutoff, the medical oncologist may make, in their best clinical judgment, a decision to maybe run more testing, try to clarify more things about the behavior of this tumor or how we expect the tumor might behave, because they are notoriously unpredictable tumors.

Sometimes with a tumor that comes from connective tissue cells called a soft tissue sarcoma, mitotic index can be prognostic. And we know from published data that dogs with a higher mitotic index, particularly over 19, for example, tend to do worse in the long term than dogs who have a lower mitotic index, usually under 10.

And again, this kind of goes hand in hand with grade and as part of how you grade these tumors. Melanoma, greater than three tends to be more aggressive. So sometimes we have very specific data that’s linked to mitotic index that we can use to give people an idea of how aggressive the tumor might be and why we might want to try a more aggressive therapy and make those recommendations versus not.

[00:11:30] >> James Jacobson: So those are three tumors where knowing the mitotic index number is going to influence your treatment choices in the regimen. Are there some cancers where it’s not as important?

[00:11:41] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yeah. Plasma cell tumor is a great example. It can be oftentimes a more liquid cancer. It comes from an immune system cell called a plasma cell. But even when we have a solid tumor, like a, a lump on the skin, those are tumors that tend to have very high mitotic indexes, like scary high. We’ll be like this number seems really large.

[00:12:00] >> James Jacobson: What’s a scary high number in a-?

[00:12:03] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Oh, like it depends, but like 20, 30, 40, 60, you know, and it may be a tiny little tumor with a very high mitotic index and you’re like, oh wow, this thing is going to take off. And sometimes, you know, typically tumors with high growth indexes like that, they will grow faster, but oftentimes plasma cell tumors do grow quickly or they have that high mitotic index.

But oftentimes with a small lesion that solitary surgery is the sole thing that’s needed and then monitoring going forward. So there are times when mitotic index seems high and scary, but isn’t necessarily as big of a deal, like in plasma cell tumor. There are other times when you get a number and we don’t really have data to say, is there a specific cutoff where we get concerned, like in mast cell tumor or melanoma or soft tissue sarcoma. Not every tumor has that well-defined.

And so there’s a subjective impression then that the higher the number is, you know, the more concerning it is, but again, it’s not just one indicator in looking at tumors and tumor biopsies like that. It’s, it’s one factor amongst many that goes into that decision-making process.

[00:13:17] >> James Jacobson: And we’re going to have you on another podcast episode to talk about staging, which of course is another one of those factors.

But in terms of mitotic index, have you ever been surprised where you got either a high number and you go oh no, this is really bad, but then you turned out to be able to do something more substantially than you thought? Or conversely, where it was a low mitotic index and it turned out to be a lot more aggressive?

[00:13:38] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yeah, absolutely.

Again, it, mitotic index is just one factor amongst many that goes into determining tumor behavior, that goes into clinical decision-making. So I have had tumors with higher mitotic indices where I’m more concerned that this is going to be aggressive, and that led me to treat perhaps more aggressively than if it had been lower.

And then one hopes that that translates into a better outcome of making that decision. And I’ve had those dogs do, you know, many dogs do really, really well. And then other times where we’ve had what appears to be a low grade tumor then metastasizes or spreads very unexpectedly, that has a low mitotic index, it’s sort of playing by the rules, so to speak, and then behaves in an unexpected fashion.

[00:14:26] >> James Jacobson: Okay. So I understand you look at a variety of different factors when you make your treatment decision, but what are some examples of treatment decisions that might be impacted more heavily by mitotic index?

[00:14:39] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: For things like mast cell tumor and soft tissue sarcoma, for example, higher mitotic indices usually correlate with higher grade tumors, in which case I might be more inclined to recommend things like chemotherapy after surgery. So for many, what we call solid tumors, which are, let’s think of them as lumps and bumps on the body or in the body, most solid tumors you want to take out that tumor, typically via surgery if you can.

But occasionally we will have higher grade tumors with high mitotic indices that, even though we got the entire tumor out surgically and we feel good about what we call that local therapy, we’re worried about the potential for the tumor to metastasize or spread down the line because of some concerning indicators on their biopsy, and that can be one of them.

[00:15:30] >> James Jacobson: Got it.

[00:15:31] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: And so if that’s the case, we may lean towards recommending chemotherapy. And there are many different types of chemo options, as you can imagine, and many different scenarios here, but that would be one reason why we might skew towards postoperative treatment, or at least a very proactive monitoring program, if we’re not doing chemo.

[00:15:52] >> James Jacobson: You mentioned earlier that, you know, the pathology lab that is used plays a big role in the results you get, or can play because they do it the way you want. Is that something that I, as a dog owner, would want to even be involved with thinking about or talking about, or is it basically you work with the lab that your vet or your veterinary oncologist uses?

[00:16:15] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yeah, usually most people, it can be daunting from so many angles to have to wrap their head around a cancer diagnosis and any information they may be getting, not just from me, but other sources, the internet, friends, other veterinarians. So, and that’s natural, right? We want to, we have a diagnosis, we want to educate ourselves and get as much information as possible to help us make decisions.

With pathologists, I would say that the onus is not really on the pet person to know, you know, which pathologist to use. Or if they have a preference, it’s rare that I would have someone express a preference, but if an owner says, Hey, you know, I, I really like this lab or I’d like a second opinion, you know, I usually am helping inform that decision for them.

You know, let’s say we sent out a sample to one of the two main private labs in the country, Antech or IDEXX, for example, and we want a second opinion. Sometimes we’ll get an internal second opinion within that lab or the other lab, sometimes we’ll go academic, an academic institution like Cornell, Colorado, University of Pennsylvania. I’m not saying those because they’re necessarily a preference, but just to give you an example.

[00:17:27] >> James Jacobson: I believe you went to Cornell.

[00:17:28] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: I went to Cornell and Penn.

[00:17:29] >> James Jacobson: Oh okay. Whoa.

[00:17:30] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: But for example, University of Pennsylvania has a great dermatopathologist there who heads their department. So sometimes we will reach out to people specifically, but I would say that it’s not necessarily something that the pet owner needs to overly concern themselves with. Not because their opinion’s not important, but sometimes it’s hard to know exactly who the best person is for this particular scenario.

And because we work in the field and we work in a very small community, oftentimes we’ll be able to direct people to who we think is, is the best person if we need a second opinion or a first opinion.

[00:18:06] >> James Jacobson: How common is it to do, you know, mitotic index early on, and then maybe later on after you’ve done chemotherapy or other treatment? Would you basically, you know, get a biopsy once and then-

[00:18:18] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: You mean rebiopsy?

[00:18:20] >> James Jacobson: -another biopsy and then another report, and then look at the mitotic index, hopefully decreasing.

[00:18:25] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yeah.

So it’s interesting. It depends on – you know, oftentimes we don’t know. If we rebiopsy and there’s a lower mitotic index, you know, subjectively we might feel better about that. Maybe the tumor’s not growing as fast or we’ve damaged it in some way, but I would say that there’s not a lot of data at all about rebiopsying tumors and seeing where the mitotic index has changed and if that’s prognostic. Meaning if it makes a clinical difference.

So even if it has changed, does, does it mean anything? And are we just putting them through additional biopsies, measuring something that really is meaning less in the long run in terms of how it changes over time. We just, we just don’t know that. Where rebiopsy of tumors is helpful, sometimes, is not necessarily as much we’re looking at mitotic index, but if we are looking at, let’s say, a metastatic lesion, and we want to biopsy that and see if and how those cells have changed, genetically what the architecture, the composition of that metastatic lesion is versus the primary, can we use that for targeted therapy and in some other, in some other way to learn how to change our protocol. Sometimes we will do that and that’s going to become more common as we understand and have better panels that can identify tumor mutations that are targetable. We’re a little bit lagging in relation to human medicine with that.

But again, mitotic index comes into play, but it’s, you know, that has a lot of other factors than just mitotic index that, that influence those decisions if we rebiopsy a tumor, how we change the treatment protocol of what the prognosis is.

[00:20:08] >> James Jacobson: Awesome. Well, Dr. Brooke Britton, thank you so much for being with us today and, and explaining mitotic index. We will have you on another show and we’ll talk about staging. Thanks so much.

[00:20:18] >> Dr. Brooke Britton: Yeah, my pleasure.

[00:20:21] >> James Jacobson: Well, there you have it. Mitotic index. It’s important and it changes based on lots of different factors. We will put some links in the show notes to some pictures to help you understand a little bit more about what the pathologist is looking for when they determine mitotic index.

I want to thank you for joining us today and hitting that play button. We have a whole bunch of information to help you help your dog with cancer at DogCancerAnswers.com. That’s where you can listen to and read all of our back episodes of this podcast.

If you found this helpful, please do us a favor and tell a friend about Dog Cancer Answers. It helps us grow the show and it lets other dog lovers find out about this when they really need the information. Stay tuned for more shows from Dog Podcast Network – ‘ cause not everything we do here at DPN is related to dog cancer – shows that you can listen to right now.

I’m James Jacobson. From all of us here at Dog Podcast Network, I want to wish you, and your dog, a very warm Aloha.

[00:21:33] >> Announcer: Thank you for listening to Dog Cancer Answers. If you’d like to connect, please visit our website at dogcanceranswers.com, or call our Listener Line at (808) 868-3200. And here’s a friendly reminder that you probably already know: this podcast is provided for informational and educational purposes only.

It’s not meant to take the place of the advice you receive from your dog’s veterinarian. Only veterinarians who examine your dog can give you veterinary advice or diagnose your dog’s medical condition. Your reliance on the information you hear on this podcast is solely at your own risk. If your dog has a specific health problem, contact your veterinarian.

Also, please keep in mind that veterinary information can change rapidly, therefore, some information may be out of date. Dog Cancer Answers is a presentation of Maui Media in association with Dog Podcast Network.

Hosted By

SUBSCRIBE ON YOUR FAVORITE PLATFORM

Topics

Editor's Picks

CATEGORY